On the stiflingly hot morning of Aug. 9, 1913, it seemed the Somaliland Camel Corps just might die almost before it had been truly born. In the shadow of a barren peak named Dul Madoba (Black Hill) deep in colonial British Somaliland, Richard Corfield watched as an overwhelming horde of more than 2,000 mounted Muslim warriors descended on his tiny command.

A young and headstrong British political officer, Corfield had been charged by Geoffrey Francis Archer, Somaliland’s acting commissioner, to organize a 150-man camel-mounted constabulary to police and patrol the coastal region around the Gulf of Aden port of Berbera, capital of the protectorate. Though on paper Britain ruled some 68,000 square miles of the Horn of Africa, a charismatic Somali tribal leader named Mohammed Abdullah Hassan had effectively reduced London’s actual control to an increasingly precarious coastal foothold.

Somaliland was one of Britain’s last colonial acquisitions. While the region offered relatively little in the way of valuable resources, the British were eager to cement control of coastal supply centers from which to support the vitally important naval base across the gulf at Aden. The British also hoped to check both their European rivals and the growing power of neighboring Ethiopia. So in 1884 colonial administrators established a tiny garrison in Berbera, and by 1886 the government of Prime Minister William Gladstone had forged treaties of protection and alliance with various Somali tribes in the interior to ensure supplies moved freely to the coast.

Though relatively small, the colonial presence enraged Hassan. A fervent Muslim, he resented the Western influences the British had introduced. Preaching violent resistance, he soon earned the nickname the “Mad Mullah” for his Islamic extremism and erratic behavior. Yet his charisma and ability to bridge tribal divisions soon drew thousands of followers known as Dervishes (a Persian-derived term for religious ascetics). In August 1899, at the head of an army of 5,000 men, Hassan approached the central Somali city of Burao and proclaimed a holy war against the infidels. He contented himself for the moment with raids against tribes ostensibly under British protection.

Though relatively small, the colonial presence enraged Hassan. A fervent Muslim, he resented the Western influences the British had introduced. Preaching violent resistance, he soon earned the nickname the “Mad Mullah” for his Islamic extremism and erratic behavior. Yet his charisma and ability to bridge tribal divisions soon drew thousands of followers known as Dervishes (a Persian-derived term for religious ascetics). In August 1899, at the head of an army of 5,000 men, Hassan approached the central Somali city of Burao and proclaimed a holy war against the infidels. He contented himself for the moment with raids against tribes ostensibly under British protection.

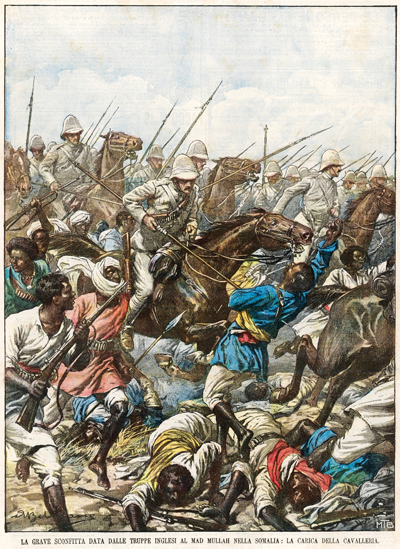

With colonial administrators only in the port cities and just 130 Indian troops on hand, the British were in no position to oppose this unforeseen native rebellion. However, fearing the loss of loyalty from the tribes they were treaty-bound to protect, they were forced to respond and over the next five years launched four military expeditions into the Somali interior.

The Camel Corps functioned essentially as the muscular arm of the British district commissioners, isolated political officers who themselves acted as intermediaries and arbitrators among the various tribes

The British initially employed a hastily armed and poorly trained force of local tribal levees. When these Somalis proved unreliable, large numbers of regular troops were shipped in from other parts of the empire. Hassan used hit-and-run attacks against the lumbering British columns, frustrating their efforts to lure him into a decisive engagement. While these expeditions weakened Hassan, they exhausted the British. “The third and fourth expeditions had cost us much,” recalled Douglas Jardine, a colonial officer who served in Somaliland. “In treasure no less than £5 millions sterling; in blood the lives of many valuable British officers whom our small professional army could ill afford to lose.”

Unwilling to maintain a sizeable military force in Somaliland, London agreed to an admittedly tenuous nonaggression treaty with the Mad Mullah and withdrew most of its regular troops in 1905. Within a few years, however, Hassan broke the terms and resumed raids against tribes allied with the colonial government. The exasperated British responded with what they dubbed the “elastic militia system,” wherein authorities would provide loyal tribesmen with arms and ammunition to mount their own defense. As Jardine bluntly put it, “They were expressly informed that they should not look to us in the future either for military assistance or to settle their intertribal disputes.”

The plan was a disaster. With all controls removed, Somalis used the British-supplied weapons to settle scores and engage in intertribal warfare on an unprecedented scale. An estimated one-third of the male population perished in the resulting years of bloodshed. Meanwhile, emboldened by the British withdrawal, Hassan and his forces raided deeper into British Somaliland.

By 1912 the military situation had grown dire—Hassan’s forces were raiding the outskirts of the coastal cities, and the British colonial administration was in danger of being literally pushed into the sea. It was at that point Corfield arrived, bearing Archer’s mandate to raise a Camel Constabulary of white officers and Somali men to police the coastal region. While slower than horses, camels could carry more weight, and their ability to forgo water for long periods was a coveted trait in Somaliland’s arid climate. By year’s end the Camel Constabulary was ready to take the field. As the raiding continued into 1913, Archer resolved to protect the trade routes to the coast and ordered the corps into the Somali interior at Burao.

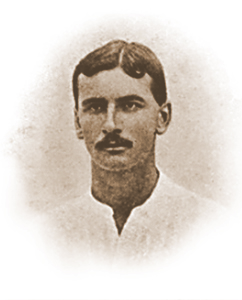

In August, on word of renewed Dervish raids, the acting commissioner sent the corps on a reconnaissance sweep. Corfield set out from Burao on the 8th with two fellow officers and 109 rank and file, 10 of whom turned back due to troubles with their mounts. In his orders Archer had reiterated that the small camel-mounted force was not to directly confront Hassan’s powerful army. Soon after the unit set out, however, fleeing tribesman reported the presence of a large Dervish raiding party near Idoweina, some 35 miles to the southeast. Soon after the corps went into camp that night, 300 irate, armed tribesmen arrived and pleaded with the British to help them recover their stolen stock. Corfield—just 31 years old and with precious little military experience—decided to attack at dawn.

The decision played into the Mad Mullah’s hands. He counterattacked in force, sending the tribesmen scurrying into the surrounding bush. Chanting praises to Muhammad, the Dervishes then attacked the surrounded Camel Constabulary in successive waves, their withering fire soon putting the corps’ single Maxim gun out of action. As Corfield sought to clear the gun, he was shot through the head and killed. For five hours the survivors of his shattered command sheltered behind their dead camels and held off Hassan’s forces till the latter ran out of bullets. When the Dervishes finally withdrew, only 25 defenders remained standing. Thirty-five lay dead, 17 wounded. Another two-dozen had fled with the tribesmen and were later drummed out of service.

While the survivors counted 395 Dervish dead on the field and estimated total enemy casualties at closer to 600, the battle went down as a humiliating defeat for the British. Taking advantage of that perception, Hassan penned a celebratory poem, opening with the lines, “You have died, Corfield, and are no longer in this world/ A merciless journey was your portion.”

The fiasco at Dul Madoba prompted the British to launch a drastic reorganization of the decimated Camel Constabulary in the spring of 1914. Renamed the Somaliland Camel Corps, the unit comprised 18 British officers and 450 rank and file, supported by the 400-strong Somaliland Indian Contingent. Commanding the overall force was Lt. Col. T. Ashley Cubitt, an experienced British army officer. Whereas the first iteration of the corps, intended solely as a constabulary force, had been led by political and administrative officials, the reconstituted force would be tasked with engaging and defeating Hassan, hence its relatively large and experienced cadre of military officers. The Camel Corps ultimately embraced its dual mission to both maintain civil order and engage any threatening force (i.e., the Mad Mullah) in direct military action.

The Camel Corps was not the only group undergoing reorganization—Hassan was also consolidating his power. Bringing in expert masons from Yemen, he had directed the construction of stone forts throughout his territory, including a massive fortress at the Dervish stronghold of Taleh, near the eastern border with Italian Somaliland. Of greater concern to the British was a series of well-sited fortifications atop strategically important Shimber Berris (aka Mount Shimbiris) in north central British Somaliland, which posed a direct threat to coastal trade routes.

On Nov. 19, 1914, Lt. Col. Cubitt led the Camel Corps and supporting Indian sepoys on an assault of the forts at Shimber Berris. Under the cover of steady machine gun fire, the troops advanced across exposed ground toward the waiting defenders. Three times the corps charged, and three times was bloodily repulsed. Captain Herbert William Symons fell dead mere feet from one fort’s gate, while future lieutenant general and Victoria Cross recipient Adrian Carton de Wiart lost an eye and part of an ear (his first of many wounds). Another five men were killed and 25 wounded before the force—with the additional support of a 7-pounder mountain gun hastily rushed to the field—was able to expel the Dervishes. Cubitt’s soldiers had expended more than 30,000 rifle and machine gun rounds and 34 artillery shells in the ferocious fight, and the men of the Camel Corps had proven themselves skilled and reliable fighters. The enraged Mad Mullah reportedly castrated his defeated Dervishes. Though Hassan was able to reoccupy the abandoned forts, a follow-up expedition by Cubitt in February 1915 razed the stronghold.

The Camel Corps also achieved success in countering Hassan’s raids on Britain’s Somali allies. Instead of simply arming the friendly tribesmen and leaving them to their own devices, the men of the corps organized small groups of scouts from the various tribes. The British also devised a functioning system for reacting to Hassan’s raids. Camel Corps Major Hastings L. Ismay later described it:

If a small force came through, the irregulars dealt with it on their own. If, as often happened, the enemy were out for a big thing and sent through 600 to 800 rifles, the job of the irregulars was to get the news in to the Camel Corps.…Sometimes we got up in time; far more often we failed. But the enemy never got away with a really big thing, and we gave him some bad knocks.

The new strategy sapped Hassan of men and supplies he could ill afford to lose. The Camel Corps’ enhanced presence also greatly augmented the British reputation among the tribes.

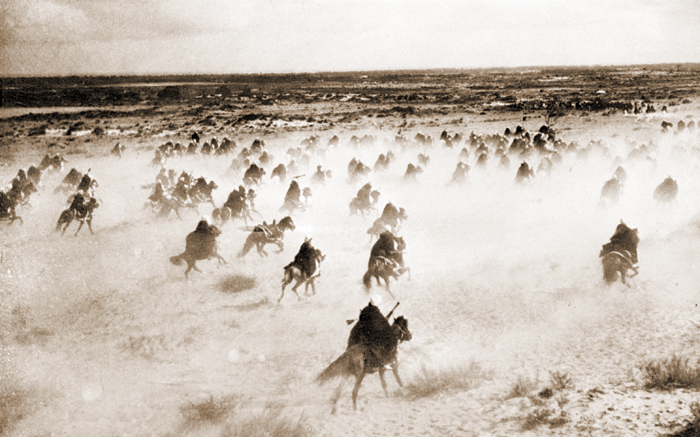

The end of World War I freed up men and equipment from Europe, and by January 1920 the British were able to move against the Mad Mullah in force. The Royal Air Force had flown 12 de Havilland DH.9 biplanes into Berbera, leaking a cover story they were to be used for oil operations. The forthcoming combination of tactical bombing—which Hassan and his troops had no experience with or defense against—and well-coordinated attacks by the Camel Corps, Indian sepoys and Somali levees overwhelmed the enemy. Ironically, Hassan’s abandonment of his mobile insurgent strategy and subsequent reliance on defensive fortifications had allowed the British to isolate the leader and his followers, with devastating consequences.

On January 27, under the cover of machine gun and Stokes mortar fire, the fast-moving Camel Corps stormed the fort at Jidali. Many of the Mad Mullah’s fanatical defenders fought to the end, praising him loudly in song even as they fired their last shots before dying in a hail of exploding shells. For three days the British bombed the imposing fortress at Taleh, largely destroying it. Amid the confusion Hassan fled, the Camel Corps close on his heels. The survivors soon surrendered. “The magic of the Mad Mullah that had for so long held his followers together,” Major Henry Rayne recalled, “was useless against the magic of the bird-men above.”

While the RAF received much credit for the operation’s success, Archer concluded it was “the sustained and determined pursuit by the Camel Corps, often on half and no rations, over a great stretch of country, regardless of privation and fatigue” that had prevented the Mad Mullah from rallying his forces. The corps had paid dearly for its hard-fought victory, however; 42 members of the unit who died on campaign between 1914 and 1920 are interred in the Hargeisa War Cemetery in present-day Somalia. Hassan fled into exile in Ethiopia, succumbing to the flu on Dec. 21, 1920. He died a broken man.

Following Hassan’s defeat, Britain’s foremost goal in Somaliland was to maintain political stability and prevent the rise of another insurgency. Ultimately—and perhaps surprising, given the history of the region—Britain was largely successful in its efforts to create a relatively stable colony free from the inherent lawlessness and violence that had marked earlier decades. Tasked with establishing and maintaining the peace were the officers and men of the Somaliland Camel Corps.

The British officers who served in the corps were a decidedly small band of brothers. By 1927 the unit comprised 379 enlisted soldiers led by just 12 officers. Each company typically had three officers, one company commander and two subalterns who led individual troops on patrols, often over great distances. As a result the junior British officers went largely unsupervised in the field, leaving them to make command decisions on the fly. That said, they had to rely on their Somali troops not only to complete their assigned missions, but also for basic survival in the unforgiving landscape of rural Somaliland.

The circumstances affected discipline and officer-soldier relations. When Murray Lewis arrived as a young Camel Corps subaltern in 1922, a fellow officer shared this advice: “If you treat the men like British troops, you will do quite well. Remember they are equal to you and me.” Such remarks reflect an unusually enlightened viewpoint in an age not known for racial tolerance.

Discipline in the corps was also very different than in other British military units. Lewis noted the Somalis required a “diplomatic discipline.” Officers never drove the men hard or physically struck them and were especially careful to respect the men’s Muslim beliefs. The bonds they established often proved strong. Peter St. Claire-Ford recalled that the Somalis regarded him and fellow officers more as “friends and advisers.” In turn, Ford’s trust in his men ran so deep that he often didn’t carry a weapon on patrol. He knew that if a fight developed, his men would protect him. When Lewis returned to Somaliland in 1950, many of his former comrades walked more than 100 miles to welcome him.

Somalis evinced great enthusiasm for the unit. A call for 20 recruits might yield as many as 200 applicants. “It was a great social attribute,” St. Clair-Ford explained, “to have a son in the Camel Corps.” The unit recruited from all tribes, but its members embraced a “corps first” ethos, considering themselves members of a distinct family that superseded all other allegiances. When the unit engaged in actions against a particular soldier’s own tribe, he would often insist on participating in order to demonstrate his loyalty to the corps.

The Camel Corps functioned essentially as the muscular arm of the British district commissioners, isolated political officers who themselves acted as intermediaries and arbitrators among the various tribes. Tribal disputes centered mostly on grazing or water rights, as well as the theft of camels—which remain a critical source of transportation, not to mention milk and meat. The corps supported the district commissioners in their efforts to defuse such potentially explosive disputes before they got out of control. “One way to do it,” corps officer John A. Stevens explained, “was if the tribe misbehaved, you sent out a patrol, rounded up 100 camels and told them they’d get them back when [the tribe] started behaving.”

The Camel Corps also served in a humanitarian capacity. During the inevitable seasons of severe drought, the colonial administration set up relief camps. The corps assisted with both the protection of the camps and the movement and distribution of relief supplies, using their pack camels to bring water and rice to the people.

At the outset of World War II, in August 1940, the Somaliland Camel Corps helped wage a valiant but futile defense against a vastly superior Italian invasion force. The British ultimately evacuated, the corps disbanded, and its Somali members dispersed. When the British recaptured Somaliland the following spring, they reactivated the corps, which promptly went to work rounding up Italian holdouts and deserters. In 1942 the army replaced the Camel Corps with a fully mechanized unit known as the Somaliland Scouts, which remained active until British and Italian Somaliland merged in 1960 to form the independent Republic of Somalia.

Dictator Mohamed Siad Barre staged a Marxist coup in 1969. Decades of repressive authoritarianism followed, leading to a devastating civil war and resultant famine that left Somalia in a state of anarchy. The subsequent rise of the radical Islamic terrorist group al-Shabaab, and the ongoing regional and international efforts to suppress it, only make the story of the Mad Mullah and the Somaliland Camel Corps all the more relevant today. These brave and resourceful men, British and Somali alike, brought stability to a land that has rarely seen it. MH

Nicholas Smith is a U.S. Army Reserve officer and works for the Massachusetts National Guard. For further reading he recommends The Mad Mullah of Somaliland, by Douglas Jardine; Sun, Sand and Somals, by Henry A. Rayne; and Churchill and the Mad Mullah of Somaliland, by Roy Irons.