Nathaniel Collins McLean wasn’t exactly an unknown in the Union Army. His father, after all, was the eminent John McLean, one of two Supreme Court justices who voted in the minority in the court’s infamous 1857 Dred Scott decision—a verdict that helped accelerate the race to civil war four years later. When outright war finally erupted in April 1861, Nathaniel, a 46-year-old Harvard Law School graduate, left his law practice in Cincinnati and volunteered to fight for the Union. He raised the 75th Ohio Infantry, soon to join Maj. Gen. John Frémont’s Mountain Department, operating in western Virginia, and was commissioned its colonel on September 18.

In the spring of 1862, during Confederate Maj. Gen. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson’s legendary Shenandoah Valley Campaign, McLean was at last given a true opportunity to show he wasn’t simply a lawyer, but a fighter, too. That three-month campaign would prove undeniably forgettable for Union forces, but at the May 8 Battle of McDowell, with the Federals in peril, McLean led the 25th Ohio and 75th Ohio in a daring attack up a steep hill to wrest away the tactical initiative from Jackson and allow an outgunned force to withdraw under cover of darkness. McLean’s commander, Brig. Gen. Robert H. Milroy, was quick to praise the colonel and his men for their “undaunted bravery” in the face of a superior foe.

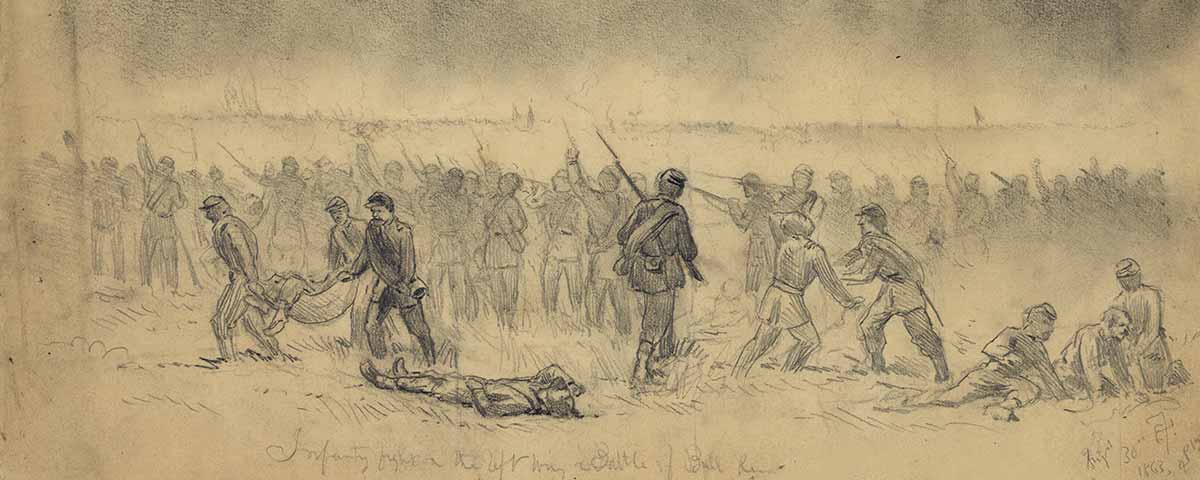

Four months later, on the “Plains of Manassas,” McLean’s bravery while facing a formidable opponent would be thrust into the spotlight yet again. This time, the stakes even higher, the middle-aged lawyer from Cincinnati and his plucky Buckeyes saved the Union Army of Virginia from possible annihilation. »

[dropcap]S[/dropcap]tonewall Jackson first drew the enmity of Northern opponents with his immortal stand on Henry Hill at the First Battle of Bull Run—the turning point of a shocking Confederate victory on July 21, 1861. Victories during the 1862 Valley Campaign and at Cedar Mountain, Va., on August 9, 1862, had only added to his lore—so much so that he became almost the singular focus of Army of Virginia commander Maj. Gen. John Pope when he squared off with Jackson at the Second Battle of Bull Run later that summer.

Brig. Gen. John F. Reynolds (National Archives)

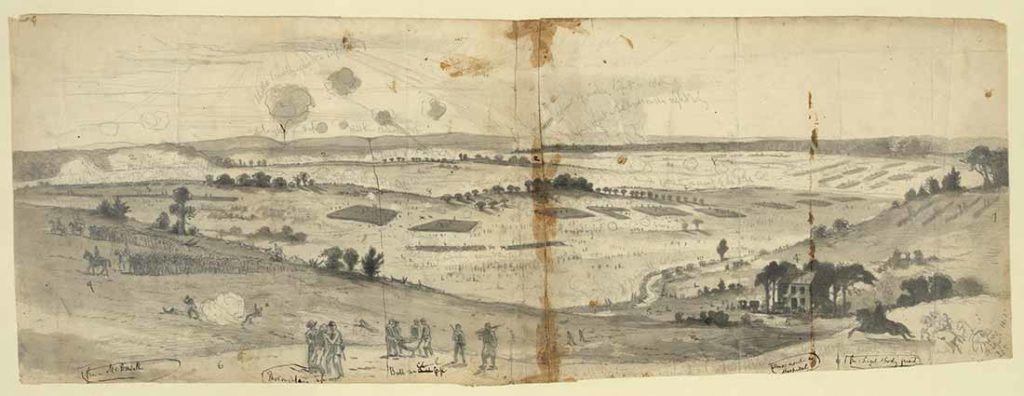

On August 30, the battle’s third day, Pope had convinced himself that he was on the verge of crushing Stonewall, who was aligned on a wide front behind an unfinished railroad cut. But in massing his forces on Jackson’s front, Pope had unwittingly overlooked the presence of the Army of Northern Virginia’s other wing, commanded by Maj. Gen. James Longstreet. Pope had left a limited force on Longstreet’s front on Chinn Ridge, to the left of the Warrenton Turnpike: Brig. Gen John F. Reynold’s Pennsylvania Reserves and two small brigades. When an afternoon attack on the Deep Cut led by Maj. Gen. Fitz-John Porter was bloodily repulsed, the potential destruction of Pope’s entire command suddenly seemed quite possible.

One of the two brigades supporting Reynolds on Chinn Ridge was McLean’s—consisting of the 25th, 55th, 73rd, and 75th Ohio Infantry. Earlier in the afternoon, pickets from the 4th New York Cavalry had informed 1st Corps commander Maj. Gen. Franz Sigel that the enemy “were moving against our left.” Sigel relayed a message to Pope, who reportedly had already received similar intelligence from Reynolds, Porter, and Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell. Even with Sigel’s report, the commander incredibly failed to give these warnings the credence they deserved. Pope remained seemingly aloof to the extent of the Confederate dispositions and decided to make only a token gesture to reinforce his left, instructing his chief of staff, Colonel George D. Ruggles, to order Sigel to send a brigade to “that bald hill.”

About 2 p.m., Ruggles rode to Sigel’s headquarters on Dogan Ridge to find the German general conversing with a group of officers, including Brig. Gen. Robert Schenck, a division commander, and the blue-eyed, bushy-bearded Colonel McLean, an acting brigadier. Ruggles directed Sigel to place a brigade “upon the bald-headed hill” south of the Warrenton Turnpike, mimicking the apathetic wave that Pope had used to identify the position.

“What bald hill?” Sigel retorted. McLean pointed southward to Chinn Ridge and asked Ruggles if that was the hill in question. “General Pope directed me to order the brigade to occupy that bald hill,” Ruggles replied and again imitated Pope’s vague wave toward Henry Hill and Chinn Ridge. Having witnessed the exchange, Captain Edward H. Allen of the 73rd Ohio concluded that “Ruggles did not feel confident of his own knowledge of this specific position which this brigade was to occupy” and offered only a verbatim repetition of Pope’s order.

Sigel dutifully ordered Schenck to send McLean’s brigade and Captain Michael Wiedrich’s Battery I, 1st New York Light Artillery, to support the Pennsylvania Reserves, then posted on the ridge’s southwest face. When McLean arrived, he deployed Wiedrich’s four-gun battery on Reynolds’ right flank and positioned his infantry regiments on the eastern slope, a short distance behind the guns. Still fearing for the safety of the army’s left flank, Reynolds was relieved to see McLean, telling him: “I will call upon you when necessary.”

About then, McDowell would be responsible for one of the war’s most ill-timed commands. It was nearly 4 p.m., and Porter’s men were retreating furiously from their setback at the Deep Cut. Although Sigel’s troops and Union cavalry had managed to restore some order, McDowell rode to Reynolds’ position near the Chinn House and, upon finding him, gesticulated across the turnpike and shouted: “General Reynolds! General Reynolds! Get every man into line and get away there.”

An astonished McLean first learned of Reynolds’ departure when the Pennsylvanians marched across his front. McLean sent an officer to Reynolds, requesting orders. The general warned of the strong Confederate force on the army’s left flank and implored McLean “to take care of himself.” McLean pondered his options: Should he follow Reynolds northward across the pike or stay and fight what would certainly be a losing proposition? With little hesitation, McLean determined that “the object was to maintain the position on Bald Hill [Chinn Ridge], and it seemed to me clearly my duty to hold the position until I was either ordered to retire or driven off by a superior force.”

McLean attempted to stretch his 1,500-man command to cover the ground that Reynolds’ Reserves had abandoned. The Ohioans trudged up the ridge and deployed into line facing west, with Wiedrich’s battery in the center and two regiments on each side of it. For McLean, the prospects were not promising. He had to buy as much time as he could.

Longstreet’s massive attack, led by Brig. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Division, opened about 4 p.m. McLean and his men plainly saw the onslaught beginning to wreak havoc south of the Warrenton Turnpike. They watched as Hood’s Texans overran Colonel Gouverneur K. Warren’s diminutive Zouave brigade on a ridge just west of Young’s Branch. Then they witnessed the swift defeat of a brigade of Pennsylvania Reserves and Captain Mark Kern’s Battery G, 1st Pennsylvania Light Artillery, units that McDowell had rushed back when he realized to his dismay what was happening.

Hood’s men occupied the rise upon which those Federals had been overrun, but Wiedrich’s German gunners opened fire with their four 10-pounder Parrott guns to disrupt the Confederate advance. The Texans pulled back momentarily into woods farther to the south of McLean’s main position, and then began to scatter in some confusion under the Buckeyes’ fire. Individual regiments charged up the ridge toward the Ohioans, only to be hurled back with heavy losses.

Brigadier General James L. Kemper’s Virginia Division had advanced on Hood’s right flank, however, and soon emerged as another threat to McLean’s tenuous position. The colonel ordered Wiedrich to “turn two pieces of artillery upon them,” but before the guns could be fired, he was assured by an unidentified “someone who professed to know” that Kemper’s battalions were Federals moving to his support. McLean’s “first and better judgment” had been correct, but the fog of war had obscured reality. He countermanded the orders to Wiedrich and “assured” the officers of the 73rd Ohio that the troops moving toward them were friendly. Only temporary confusion in Kemper’s ranks granted McLean a brief reprieve, allowing the Buckeyes the time to deal exclusively with a fresh rush of Confederates pouring out of the woods in their front.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]‘It seemed to me clearly my duty to hold the position until I was either ordered to retire or driven off by a superior force.’ -Nathaniel Collins McLean[/quote]

The South Carolina brigade of Brig. Gen. Nathaniel “Shanks” Evans advanced toward Chinn Ridge so closely behind the 18th Georgia Infantry and the Hampton Legion that the Ohioans were convinced the Confederates were attacking in columns. Although several of their officers fell as the Carolinians approached the ridge, the contingent continued to surge forward, “yelling like demons.” But, recalled one Ohioan: “We poured such a murderous volley into them that they retreated to the cover of the woods again.”

McLean’s ordeal was far from over, however. To the south of his position, Confederate cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart advanced every battery he could get his hands on and enfiladed the Ohioans’ battle line. “The shot and shell came plowing down our line,” wrote Major Sam Hurst of the 73rd Ohio. After Confederate officers sorted out their jumbled ranks, Colonel Jerome B. Robertson rallied the 5th Texas to the right of Evans’ South Carolinians. Colonel Peter F. Stevens, commanding Evans’ Brigade, attempted an advance against McLean, but “found the line halted and staggering under the murderous fire of grape, canister, and musketry.” He shouted “charge” but “found it impossible for officers to make themselves be obeyed” under the Buckeyes’ murderous fire. Hood arrived and implored the South Carolinians to capture Wiedrich’s battery, but McLean’s men quickly blunted that attack.

As a 25th Ohio officer vividly recalled:

They marched up like mad men, not a charge, but marched up in solid column without firing a shot. As fast as one regiment was mowed down like grass by the scythe, another stepped up in its place. I know that our brigade killed and wounded more than their own number.

Although McLean had held his ground, a crisis had developed on his left with a determined push by Robertson’s 5th Texas. The Federals were forced to yield, particularly with a subsequent attack by a second line of troops in Kemper’s command. Union reinforcements had arrived in an attempt to extend McLean’s line, but it was too late—those fresh troops were swept back as the 73rd Ohio retreated on McLean’s left.

Evans’ South Carolinians then surged out of the woods and again charged up the ridge, emboldened by the success of the 5th Texas. With Rebel bullets zipping through the air, McLean ordered the balance of his brigade to change front to the left. The 25th Ohio attempted to execute the maneuver, but “the fire was so terrible and the noise of battle so great that it was impossible to be heard or do anything without confusion.”

Seeing the colors of the 73rd Ohio falling to the ground and Confederates rushing to capture them, the 25th Ohio broke. Caught in the same vise that shredded the 73rd Ohio, the 25th streamed over the crest of Chinn Ridge and retreated toward the woods in their rear. Wiedrich’s gunners quickly limbered up and raced back toward Henry Hill, narrowly avoiding capture. The next regiment to the right, the 75th Ohio, fared little better. Its line “doubled up like a hinge so that the right and left companies came together.” As a result, only two of its companies successfully changed front.

Colonel John C. Lee of the 55th Ohio, on the far right of McLean’s line, saw the 75th Ohio waver and called out to his regiment: “Stand to it, boys, and do not run!” Then, under a heavy crossfire, the 55th Ohio wheeled to the left and advanced toward the charging South Carolinians and Texans. As the Ohioans wheeled to face their enemy, Lee noticed that the regimental flag was concealed in its casing and bellowed out, “Unfurl and let them see that flag!” The 55th’s color-bearer “dashed it out upon the air” in a scene of martial grandeur. With fixed bayonets, the 55th Ohio and two companies of the 75th Ohio fired several destructive volleys into the left of the Texans and Carolinians surrounding the Chinn House at a range of less than 200 yards. The Carolinians broke for the woods “like the devil was after them,” according to one Buckeye. When Private D.H. Gilliland of the 55th Ohio saw the Carolinians in headlong flight, he jumped up in the air and shouted, “Give it to them, boys, we have them a-going now!”

Mettle on Dual Fronts

Courage—both moral and physical—ran deep in the McLean family bloodline. In 1857, five years before Nathaniel McLean’s display of physical resolve at Chinn Ridge saved a Union army from annihilation, his father, U.S. Supreme Court Justice John McLean, exhibited exceptional moral courage in the Dred Scott decision that became a catalyst for the Civil War.

In Dred Scott v. Sandford, the Supreme Court considered the appeal of African-American Dred Scott, born into slavery in Virginia in 1795. By the early 1830s, Scott had been sold to Dr. John Emerson, an army surgeon who took Scott to a military post in Illinois, a free state. They resided there two years, then moved to Wisconsin Territory, where slavery also was prohibited. In 1843, having returned to Missouri, Scott attempted to purchase from Emerson’s widow the freedom of his wife, whom he had married in Wisconsin (she was owned by another man who sold her to Emerson so the couple could remain together), and two daughters. The widow spurned his offer, so Scott sought freedom through the courts, initi-ally winning his victory before a jury in 1850. Two years later, the Missouri Supreme Court reversed the decision, returning the Scotts to bondage. Scott lost an appeal in the U.S. Circuit Court and took his case to the Supreme Court.

Not surprisingly, that court—packed with seven of nine justices appointed by proslavery presidents—did not restore the Scott family’s freedom. Instead, Chief Justice Roger B. Taney of Maryland ruled Scott had no legal standing to sue, stating: “They [African-American slaves] had no rights which the white man was bound to respect; and that the negro might justly and lawfully be reduced to slavery.”

Although Scott lost his case, it reinvigorated the issue of slavery as a topic of nationwide political discussion. McLean opined for the minority (joined by Justice Benjamin Robbins Curtis) and highlighted the 7-2 decision’s contradictions. He ripped into Taney’s faulty historical assumptions regarding the Founders’ views on slavery and took him to task on the longstanding precedent of courts honoring the freedom of slaves taken into free states. To Taney’s reasoning that African-Americans were not citizens as a result of their race, McLean opined that argument was “more a matter of taste than of law.”

McLean’s position surprised no one. He served 32 years on the Supreme Court and was an 1856 presidential candidate, and even received votes on the first ballot at the 1860 Republican Convention. On April 4, 1861—eight days before Confederate forces fired upon Fort Sumter—Justice McLean passed away. He was 76. –S.P.

McLean proudly recalled: “My men obeyed my orders in this great extremity under a heavy fire in grand style, delivering their fire…so steadily and with such terrible effect that the advance of the enemy was checked at once.” The colonel quickly rallied some men from his other regiments and posted them behind a fence line facing southward, and awaited the approach of Kemper’s rear line. Union reinforcements joined McLean’s line.

When the Virginians closed to within 40 yards of McLean’s position, the Federals rose up and fired a volley that “cut them all to pieces,” according to Ohio Private John W. Rumpel. The success was temporary—the tide had finally turned. Once Kemper’s Division sorted out its ranks and reattacked, McLean had little choice but to pull back.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”left”]Although mortally wounded, Brady refused to release his grip on the flag. Harris had to pry each finger off the staff to free it.[/quote]

The fields west of the Chinn House flamed with musketry as the Confederates blazed away at the slowly withdrawing Federals. McLean sat on his horse and watched the remnants of his brigade stream past him. Taking a last look at the enemy before leaving the ridge, a Union battle flag waving in the wind caught his attention. The flag was the 75th Ohio’s and its bearer, 21-year-old Irish lad Michael Brady, had been wounded and was now sitting upright supporting the colors. At the Battle of McDowell in May, the 5-foot-4 Brady at one point had leapt over a crest to snatch the 75th’s fallen flag. For his bravery, the men of the regiment demanded that Brady be appointed their color-bearer.

When the Southerners first appeared on August 30, Lieutenant George B. Fox jokingly called to Brady: “They will get the colors today.” Turning to look, Brady loudly declared, “If they get the flag, they’ll get old Mike. Now mind that, Lieutenant.” As the Confederates enveloped McLean’s final position, Brady rushed forward and waved the flag “back and forth in a defiant manner.” A Confederate bullet soon shattered the flagstaff, and another pierced the gallant Brady’s body. He fell to the ground, but quickly sat up and held the flag aloft. Seeing their regimental flag, McLean, Captain Andrew Harris, and a few others ran back to retrieve the colors. Although mortally wounded, Brady refused to release his grip on the flag. Harris had to pry each finger off the staff to free it. (Brady was carried off but soon died in a military hospital. He is buried in the Alexandria, Va., National Cemetery.)

McLean’s brigade—by now, mostly men from the 55th and 75th Ohio—retreated along the western slope of Chinn Ridge, screened from Kemper’s left flank by an intervening crest. (On the other side of the crest, the men in Brig. Gen. Zealous B. Tower’s 2nd Brigade, 2nd Division, 3rd Corps, were getting pounded, all part of an onslaught that threatened to unravel the army’s defenses on this sector of the field.) During the retreat, McLean turned to his adjutant and lamented, “We had been sent up there and sacrificed,” later recalling, “I do not know that I was ever so angry…in all my life.”

Confederate artillery wreaked havoc on the departing blue ranks. Sergeant Luther Mesnard of the 55th Ohio wrote of one devastating moment: “As I fell in on the right, I saw [our] color bearer[’s]…head strike the ground some twenty feet in rear of the line, while his body with the colors fell forward, a solid shot having struck him in the chin.” The Ohioans soon crossed Young’s Branch and then followed the Warrenton Turnpike past the Stone House, below Henry Hill.

As the sun sank behind the Bull Run Mountains, casting shadows across the Virginia Piedmont, McLean rode solemnly alongside his shattered brigade. At one point, he approached Colonel Lee, the two exchanging a somber glance and shaking hands without speaking. They didn’t have to. The tears streaming down their cheeks plainly told of the suffering their soldiers had endured during the battle.

Yet the Ohioans’ sacrifice had not been in vain. The courageous stand on Chinn Ridge prevented Longstreet’s attack from overrunning the left of Pope’s army, and bought the embattled Union commander the precious time needed to establish a defensive line east of the ridge on Henry Hill. Instead of being annihilated, Pope’s battered army managed to successfully withdraw.

Within days of the defeat, Pope was relieved of command and shuffled off to Minnesota Territory. McLean, however, received a promotion to brigadier general. He would go on to serve notably at the Battle of Chancellorsville and in the 1864 Atlanta Campaign, but his contributions at Second Bull Run would not be surpassed.

Scott C. Patchan, a regular contributor to America’s Civil War, is the author of Second Manassas: Longstreet’s Attack and the Struggle for Chinn Ridge and The Last Battle of Winchester: Phil Sheridan, Jubal Early and the 1864 Shenandoah Valley Campaign.