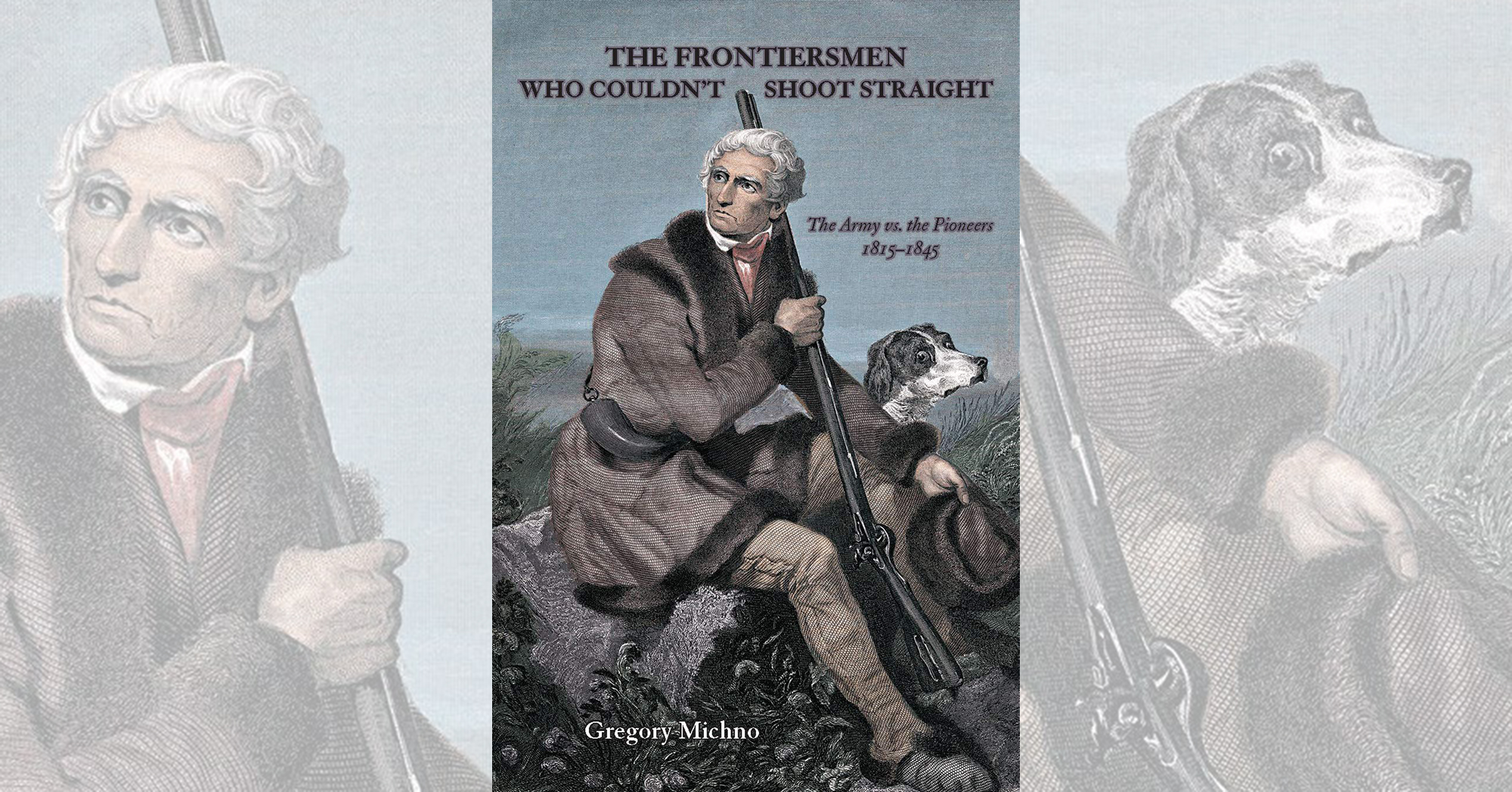

The Frontiersmen Who Couldn’t Shoot Straight: The Army vs. the Pioneers, 1815–1845, by Gregory Michno, Caxton Press, Caldwell, Idaho, 2020, $18.95

Traditional frontier heroes have no place in this book by Wild West special contributor Gregory Michno, an independent researcher who has long written about Western history, in particular the Indian wars. His February 2020 article “Half Horse, Half Gator and All Hogwash,” in which Michno asserts David Crockett and Daniel Boone epitomize the myth of the heroic frontiersmen, created more than its share of controversy. Those two fellows, viewed as American heroes in most circles, get their due (or “undue”) in this book. Michno is intent on deglamorizing, if not disparaging, the frontiersmen who operated (and sometimes ran amok) usually east of the Mississippi River but also in designated Indian lands to the west from the end of the War of 1812 to the start of the Mexican War. While the author’s research should impress anyone, many readers won’t like or appreciate the distasteful facts and contemporary quotes he presents, not to mention his pull-no-punches commentary. Even readers who find merit in his arguments will be disturbed by what they read. In short, Michno wants to turn American exceptionalism on its head and expose the widespread racism, bigotry and xenophobia he contends plagued the frontier in the first half of the 19th century.

The author makes no bones about it, stating in the introduction his concentration on the negative. “A prime reason,” he writes, “is because the contrary positive image is the one fully incorporated into the American myth. Thus, to swing the pendulum back toward the middle, the unflattering and scandalous need exposure. For debunking to have value, however, it needs to do more than replace one prejudice with another—it needs to drive out the fallacious beliefs.”

For example, Michno posits, many Americans believe the Army’s main purpose on the frontier was to protect settlers and emigrants. In the time period covered here, though, the Army, more than anything else, was trying to regulate white encroachment against the persons and property of Indians. In fact, he contends, the Army was often at odds with the many dishonest and greedy contractors, land speculators and other citizens who magnified the danger of Indian attack or property losses to Indians.

What’s more, Regular Army officers were finding out that, as Michno puts it, “Militia and volunteers were not worth the cost of the gunpowder to blow them to smithereens.” He provides many examples of citizen armies at their worst, pointing out how their willingness to do battle stemmed largely from frontiersmen’s greed for land and loot. For instance, in the 1820s U.S. Army Maj. Gen. Edmund P. Gaines wrote that white Georgians trespassing on Indian lands were “certain to produce acts of violence upon the persons or property of unoffending Indians, whom we are bound to protect.”

The story of Indian removal (Cherokees, Creeks, Trail of Tears, etc.) from the South is well known, but Michno reminds us some Southerners wanted the Indians to stay in order to cheat and rob them and sell them liquor. In the end, though, nearly as many Indians would migrate west (often on foot) as white settlers did in their iconic covered wagons on the Oregon Trail. “The Indian migration was fully as encompassing and extraordinary as the later white migration,” Michno writes. “And the Indian exodus was fraught with more menace from thieving whites than the Oregon Trail emigrants were at risk from the Western tribes.”

The Frontiersmen Who Couldn’t Shoot Straight won’t sit well with any reader proud to be an American or about anything his or her ancestors might have done to make America great. “If the 18th century emphasized progress of the human race, the 19th century emphasized distinction of the races and inequalities,” Michno writes in a section fittingly entitled “Civilizing the White Frontier.” Among the few heroes of the time, he notes, were the officer corps, “a comparative bastion of integrity, civility, discretion and fairness.” But present-day Americans, he argues, should be reading actual history instead of believing “Hollywood history.” It may not be as entertaining, of course, but Michno hopes it will lead more of us to challenge our “origin myth of self-glorification.”

—Editor

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.