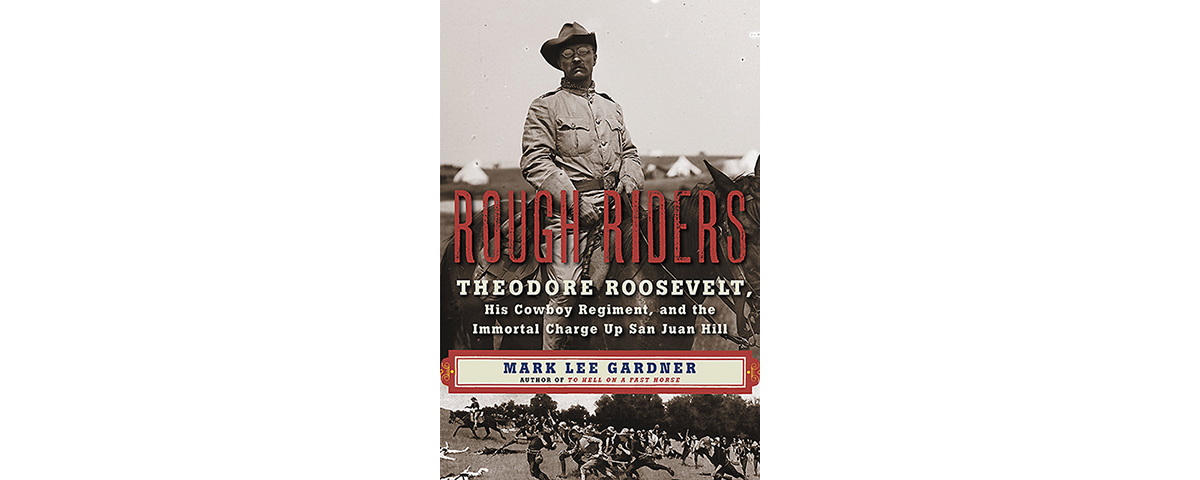

Rough Riders: Theodore Roosevelt, His Cowboy Regiment and the Immortal Charge Up San Juan Hill, by Mark Lee Gardner, William Morrow, New York, 2016, $26.99

When the Spanish-American War broke out in April 1898, the Indian wars were not long past, and many Americans were convinced their best source of cavalrymen was from among the cowboys and other horsemen in the sometimes still Wild West. Thus arose the 1st U.S. Volunteer Cavalry Regiment, commanded by Colonel Leonard Wood—who had earned a Medal of Honor pursuing the Apaches—with recently resigned Assistant Secretary of the Navy Theodore Roosevelt as his second in command. Despite an influx of well-to-do Easterners into the ranks, the unit acquired the nickname “Rough Riders.”

Soon after the troopers began training in Tampa, Fla., curious spectators proved such a distraction that Wood decreed no one could enter camp without a pass, and female visitors would require special permission. Renowned artist Frederic Remington, a personal friend of Roosevelt, was a bit miffed at the order, remarking he had never required a pass in all of his years sketching soldiers on the frontier. He was even more disappointed once admitted to camp, exclaiming, “Why, you are nothing but a lot of cavalrymen!” At that point in their transition from rugged frontier individualists to Industrial Age combatants the Rough Riders “took that as a supreme compliment,” notes Mark Lee Gardner, who has written much about the Wild West, including the fast-paced books To Hell on a Fast Horse: The Untold Story of Billy the Kid and Pat Garrett and Shot All to Hell: Jesse James, the Northfield Raid and the Wild West’s Greatest Escape.

The “splendid little war” was barely over before the Rough Riders’ exploits in Cuba became the stuff of memoir, legend, revisionism and dispute, largely guided by the politics surrounding its deputy commander’s subsequent political rise. Gardner covers the mythmaking and provides details of what the troopers actually did and where in relation to Kettle and San Juan hills they did it. While many others—including Roosevelt himself, of course—have written about the future president’s wartime adventures, Gardner’s book confirms the reality of Roosevelt’s exploits while assembling an admirably comprehensive study of the outfit’s most interesting characters, reminding the reader that T.R. was not the only one who showed true grit. For example, the author relates what happened when Sergeant William E. Dame, a 40-year-old miner in Troop E, happened upon buffalo soldiers of the 10th Cavalry near Kettle Hill.

When asked where he was going, Dame proclaimed: “Rough Riders going to take that hill. Get out of the war, or fall in with us.”

“I will be damned if those Rough Riders will get ahead of me,” replied a 10th Cavalry trooper.

As the regiments advanced side by side, another Rough Rider later recalled, “I positively assert that every face I looked into, both white and black, had a broad grin on it.”

Gardner adroitly strings together this and numerous other vignettes to present an accurate and lively narrative of the Rough Riders’ unit history, from its formation to the climactic clashes at Las Guásimas, Kettle Hill and San Juan Hill, through war’s end and its aftermath.

That aftermath includes Jan. 16, 2001, when Roosevelt became the only president to posthumously receive the Medal of Honor. He was only the second Rough Rider so honored. The first, Captain James Robb Church, was the regimental surgeon who had distinguished himself by aiding numerous wounded troopers under intense Mauser fire at Las Guásimas. Church was also the first man to receive his MOH from the president—Roosevelt, as a matter of fact—on Jan. 10, 1906.

Books about T.R. certainly keep coming. Another 2016 release worth noting is The Naturalist: Theodore Roosevelt, a Lifetime of Exploration, and the Triumph of American Natural History, by Darrin Lunde (Crown Publishing). Roosevelt could be warlike all right, but he also had a love for nature.

—Jon Guttman