HITLER HAS STOOD ACCUSED of many things over the years: being a tyrant, a warmonger, and a mass murderer. Norman Ohler’s recent book, Blitzed, labeled the Führer an opioid user and drug addict. Now, according to historian Eric Kurlander, we can add “dabbler in the black arts” to the list, and perhaps even “Satanist.”

HITLER HAS STOOD ACCUSED of many things over the years: being a tyrant, a warmonger, and a mass murderer. Norman Ohler’s recent book, Blitzed, labeled the Führer an opioid user and drug addict. Now, according to historian Eric Kurlander, we can add “dabbler in the black arts” to the list, and perhaps even “Satanist.”

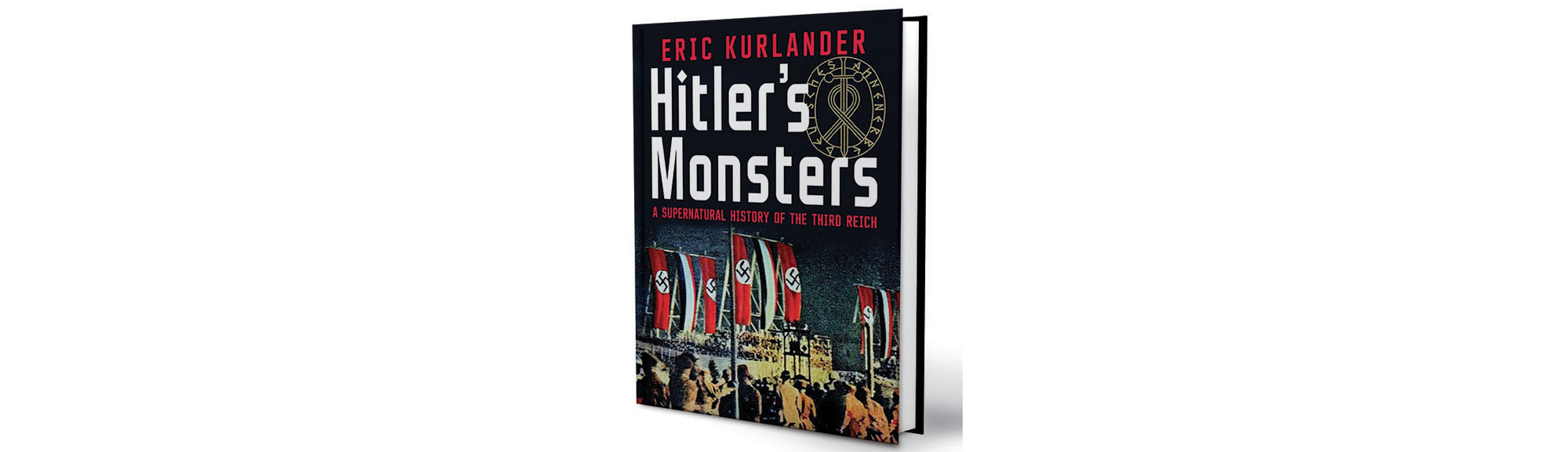

Hitler’s Monsters is a fascinating book, describing in fine detail the Nazi Party’s devotion “to occult forces, mad scientists, fantastical weapons, a superhuman Nazi master race, a preoccupation with pagan religions, and magical relics supposed to grant the Nazis unlimited powers.” In other words, if you wish to understand Hitler’s mind and the twisted ideology of the movement he started, you probably don’t need to read Mein Kampf at all. Rather, you should see Captain America: The First Avenger (2011), where our hero takes on the Red Skull—or better yet, journey back 30 years and rewatch Raiders of the Lost Ark (1981).

It turns out that Hitler and his minions believed in a lot of crazy ideas, ones that went well beyond crackpot notions of racial purity that were better suited to raising chickens than human beings. They lived in a dark mental universe of pseudoscience: notions of blood purity and mystical grails, astrology, parapsychology, Neo-Paganism, even World Ice Theory (or “glacial cosmogony”)—the belief that ice is the basic substance of the universe, that “icy moons had crashed into Earth” in ancient times and that the cataclysm had destroyed a human civilization that had already achieved a high level of development—all, it must be added, without a shred of fossil evidence. Many high-ranking Party members, especially the court around SS chief Heinrich Himmler, resurrected the worship of Holle, the supposed ancient Aryan goddess of fertility. Some would even come to call themselves “Luciferians,” worshipping you-know-who and rejecting what they felt were fatally weak Judeo-Christian notions of mercy, love, and justice.

Despite its sensationalist subject matter, Hitler’s Monsters isn’t an easy book to read. The author is aiming for a scholarly audience, and he includes the obligatory blizzard of footnotes and a great deal of “this historian said this, that historian said that” argumentation. Nevertheless, Kurlander is onto something important. It’s a cliché that our modern scientific, technological world can be a heartless place. Recognizing their own mortality, men and women instinctively seek some higher belief, something that goes beyond science and explains the mystery of our existence. As Hitler’s Monsters demonstrates chapter and verse, however, abandoning science altogether is rarely a good idea, and investing a political leader like Adolf Hitler with the status of a shaman or messiah can be positively deadly. —Robert M. Citino is the senior historian at the National WWII Museum and writes this magazine’s “Fire for Effect” column.