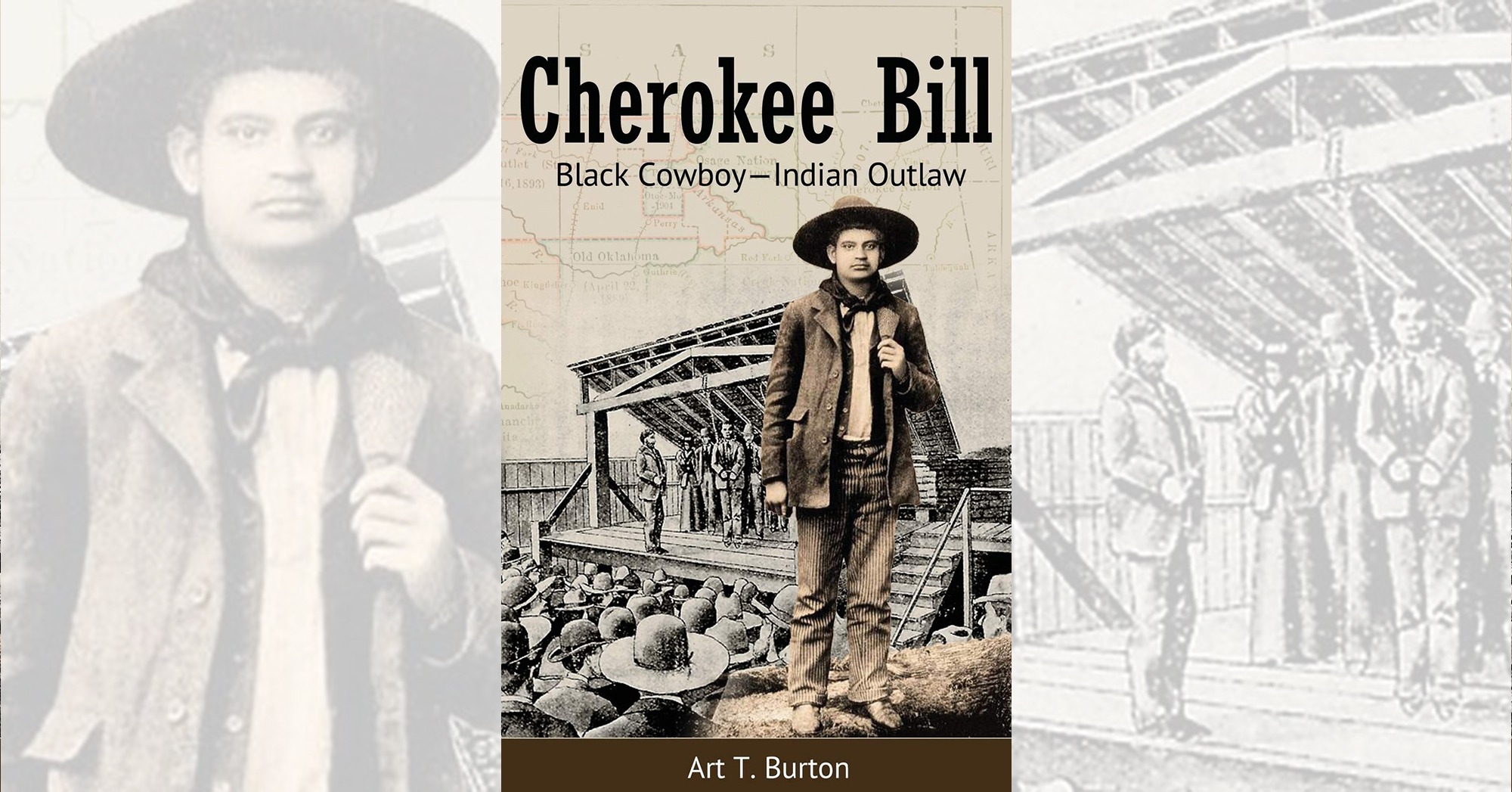

Cherokee Bill: Black Cowboy—Indian Outlaw, by Art T. Burton, Eakin Press, Fort Worth, Texas, 2020, $17.95

Since his first book on the subject in 1999 Art T. Burton has been revealing overlooked black Americans who made their mark on the American West. In 2006 he wrote Black Gun, Silver Star: The Life and Legend of Frontier Marshall Bass Reeves, the first scholarly biography of the highly regarded lawman. Burton’s biography of Cherokee Bill reminds us (as if we need it) that fame and notoriety counted on both sides of the law.

Born Crawford Goldsby, Cherokee Bill was raised in Indian Territory in the latter half of the 19th century, just before its transformation into the state of Oklahoma. Originally allotted to the Five Civilized Tribes (Cherokee, Chickasaw, Choctaw, Creek and Seminole), the territory developed into a multiethnic haven for black freedmen and slaves, as well as the progeny of mixed marriages. The varying ethnic groups coexisted uneasily—one of dual ancestry might be called “half-breed” if he looked predominantly black or “mixed-blood” if predominantly Indian. Whether or not such labels were bandied about with respect often depended on one’s reputation with a gun. Authorities strived to impose order over this unruly melting pot, often at the end of a rope, courtesy of Judge Isaac C. Parker and such lawmen as Heck Thomas and Heck Bruner. Complicating that effort somewhat was the fact that white men’s laws and Indian laws were not exactly in harmony.

By 1894 Goldsby had established himself as one of the deadliest badmen “on the scout,” robbing and occasionally killing under the name of Cherokee Bill with such confederates as Bill and Jim Cook and Sam “Verdigris Kid” McWilliams. In late January 1895 authorities caught up to Cherokee Bill, largely due to the betrayal of friend Ike Rogers. Soon after being convicted and sentenced to death, he attempted escape, in the process adding guard Lawrence Keating to the seven previous victims he admitted to having killed. But he wouldn’t escape justice. On March 17, 1896, the 20-year-old dropped through the gallows trap at Fort Smith.

As is often the case with Western biographies these days, author Burton devotes considerable scholarship toward distinguishing fact from legend—and finding plenty of truth behind the notoriety in multiple newspaper accounts of the time. This includes a series of contemporary stories in The New York Times that prove Bill’s fame reached well beyond Indian Territory. Although the narrative derails in places that could have used closer editing, Cherokee Bill should revive a short but eventful career to compare with those of Jesse James and Billy the Kid.

—Jon Guttman

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.