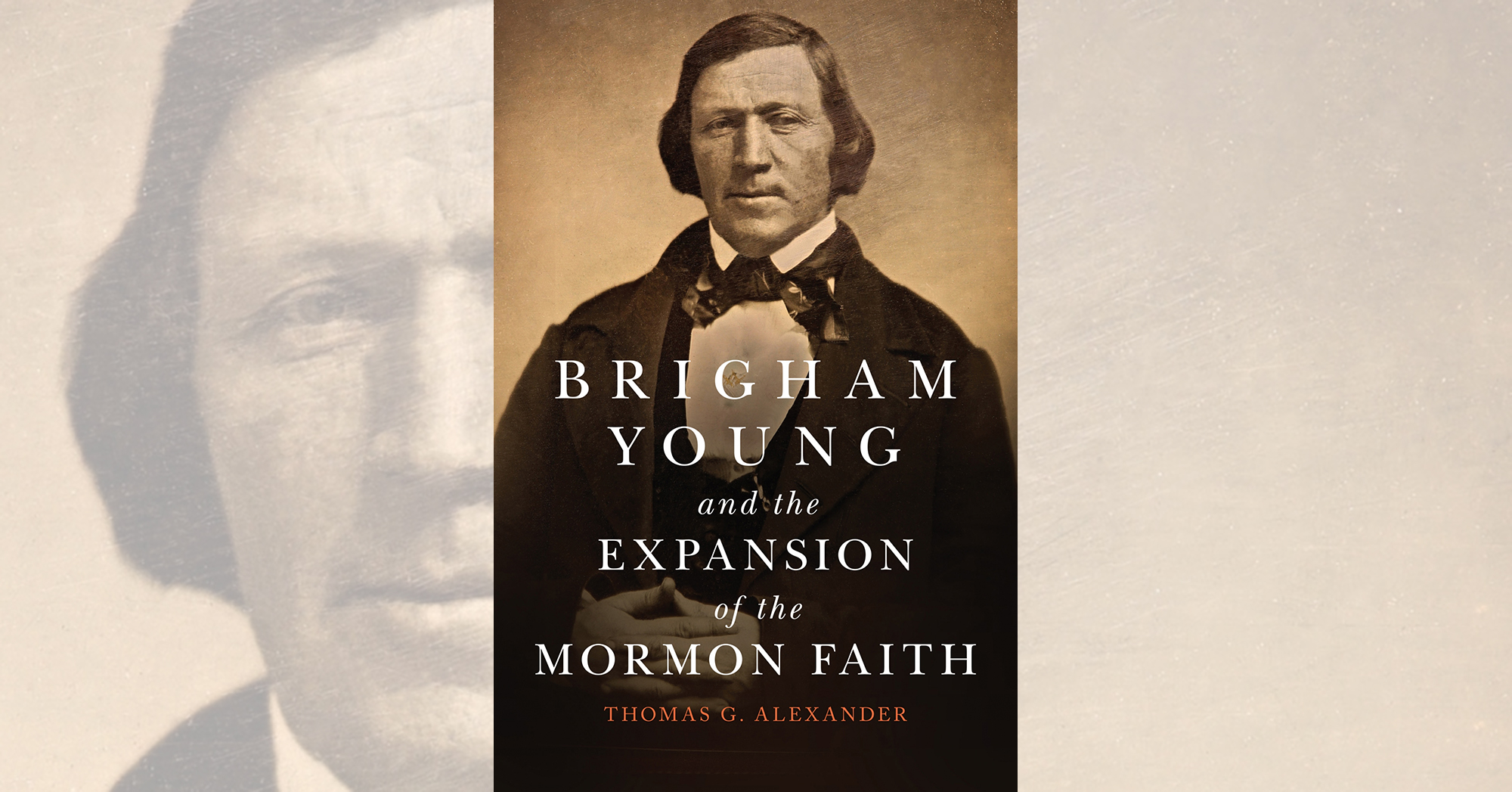

Brigham Young and the Expansion of the Mormon Faith, by Thomas G. Alexander, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2019, $29.95

Amid the sheer newness of the United States at the turn of the 19th century the Protestant faith underwent a spiritual reappraisal that came to be called the Second Great Awakening. As one consequence Christianity became even more of a house divided and subdivided against itself, as new splinter groups pursued variations of the theology in the New World. Among them was the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, or Mormons. Given the hostility that often attended these sects, a good many of them soon vanished. Mormonism, whose founding father, Joseph Smith, was murdered in 1844, seemed destined to be among them. Instead, its adherents kept migrating farther west until they found their Zion in what would become Utah and then proceeded to thrive beyond all expectations. That they achieved this success was due in no small degree to the leadership of the “Mormon Moses,” Brigham Young.

The latest biography of this epic figure of the American West, Brigham Young and the Expansion of the Mormon Faith is the work of a Mormon professor emeritus at Brigham Young University. Despite that—or perhaps because of it, with a century and a half of hindsight in which to work—Thomas G. Alexander has culled the archives to produce a balanced picture of what turns out to be an oft-contradictory life. The result is anything but hagiographical. Delving well beyond the larger-than-life character in the history books, Alexander sorts his way through a labyrinth of inconsistencies and downright contradictions in Young’s approaches to theology, relations with American Indians and equally prickly relations with non-LDS pioneers passing through Utah Territory, as well as the prospects of war between his people and the U.S. Army. This inevitably includes the notorious Mountain Meadows Massacre of the Baker-Fancher wagon train on Sept. 11, 1857, in which Young insisted he played no part. Even within the present-day Mormon fold Young’s complicity remains a subject of debate, and Alexander names names among fellow historians lined up on both sides of the matter before stating for the record that he, personally, is one of those who believes Young was not involved.

However much reverence Young still deserves for a variety of accomplishments in the history of LDS and Utah, Alexander reserves the right to call him out on his errors, setbacks and failures. The result is a portrait of a remarkable human being, but—and perhaps it takes a Mormon to remind us—a human being just the same.

—Jon Guttman