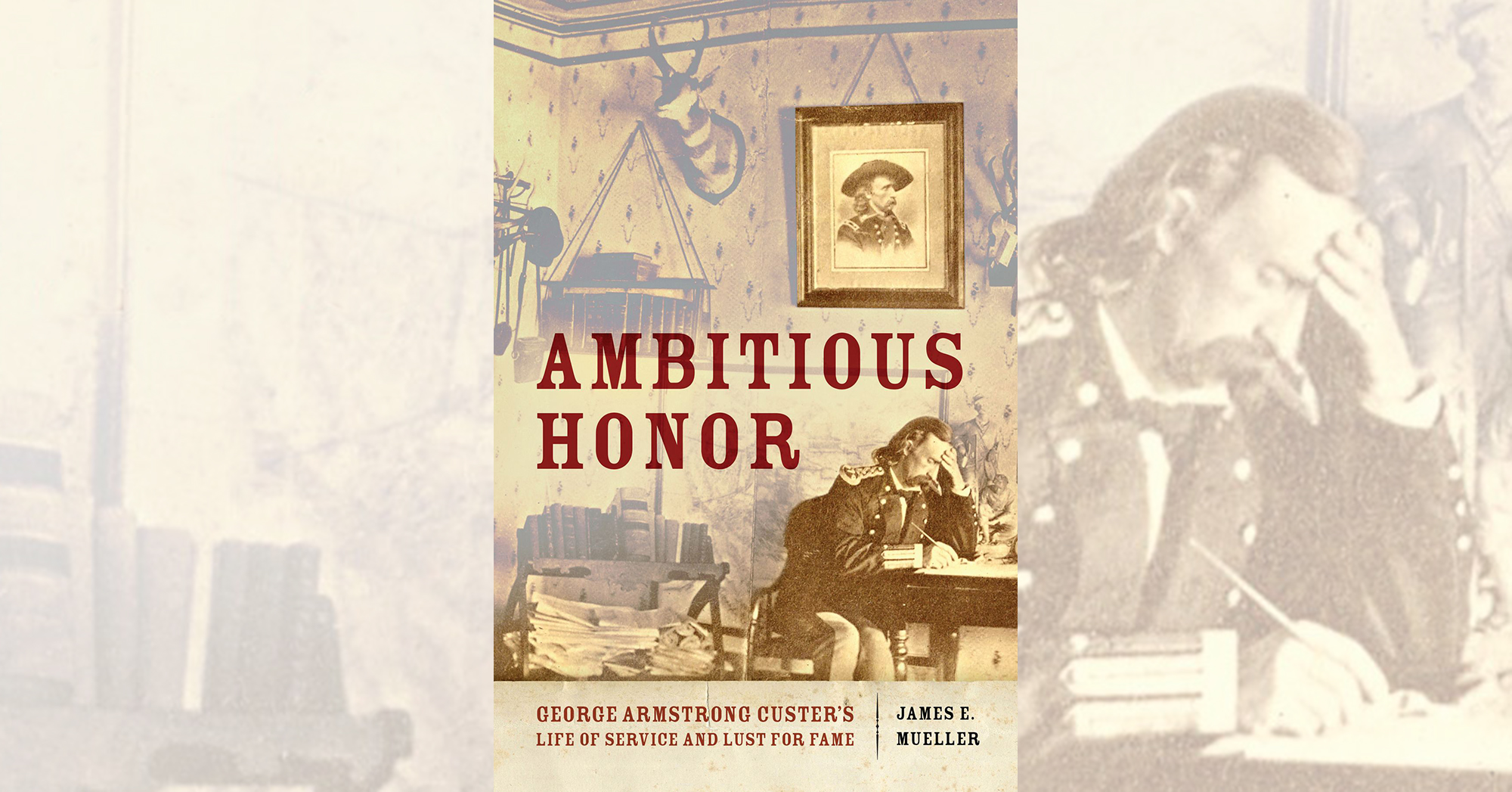

Ambitious Honor: George Armstrong Custer’s Life of Service and Lust for Fame, by James E. Mueller, University of Oklahoma Press, Norman, 2020, $32.95

There appears no end in sight to the number of books—good, bad and indifferent—authors will pen and publishers will push about George Armstrong Custer and his June 25, 1876, last stand at the Little Bighorn River in Montana Territory. Why do we need another biography of the man and his legacy? The question merits renewed consideration in the wake of T.J. Stiles’ Pulitzer Prize–winning 2015 history Custer’s Trials. Stiles seems to have plumbed every known letter the controversial soldier wrote, among countless other primary sources.

Part of the answer lies in the role “Custer’s Last Stand” plays toward our understanding of the “winning of the West.” Moreover, the scale of Custer’s defeat at the Battle of the Little Bighorn shocked the entire nation, particularly given the “Boy General’s” reputation as a successful Civil War general and Indian fighter. As author James Mueller notes, “The news of his disastrous last battle, which stood in such contrast with his images of the invincible cavalryman, was so stunning that it seared a place into the nation’s consciousness that remains to this day.” That said, this refreshing effort demonstrates there is more to the story than Custer’s military legacy. Ambitious Honor offers lessons for both the Little Bighorn novice and expert.

Those with a general interest in history will appreciate reading a clear, well-written, well-organized biography that remains focused on its subject. While providing essential details about the 1876 Little Bighorn campaign and other events, for example, it avoids ponderous tactical details regarding Custer’s Civil War battles, which would only lose the unfamiliar reader’s attention. A journalism professor, Mueller relates a focused narrative that captures the essence of the man and his diverse accomplishments and interests.

Subject matter experts might find Ambitious Honor contains little or no new information about either Custer’s personal life or his military accomplishments (and failures). They might bemoan its perfunctory treatment of the Little Bighorn, largely based on Captain Edward S. Godfrey’s 1892 account of the battle, and the lack of battle maps. Finally, they might complain that much of its research is drawn from standard, albeit reliable, secondary sources.

Notwithstanding such potential criticism, students of Custer and his last battle should appreciate the author’s fresh perspective of a man that continually defies a simple, one-dimensional interpretation of his character. Custer was not only a soldier but also a scholar who had multiple interests and experiences apart from the battlefield. “He had a remarkable talent for war,” Mueller notes, “but it was a career he was thrust into because of the times in which he lived. Custer had an artistic temperament and as such was drawn to creative endeavors like writing and performing. Those talents drew him to fields such as education, journalism, entertainment and politics.” He demonstrated these creative talents despite his poor West Point academic record.

The author’s research of Custer’s correspondence in the Elizabeth Bacon Custer and other archival collections attest to the fact his subject was an exhaustive writer of letters, which often consumed dozens of pages. Like many commissioned officers in the frontier Army, Custer took advantage of his downtime between assignments to concentrate on writing articles for such magazines as Turf, Field and Farm and Galaxy and his 1874 book My Life on the Plains—among the forerunners of literary journalism or narrative nonfiction. Only his death prevented the completion of his Civil War memoir.

We could point to Custer’s many other non-military experiences, such as the lure of New York City “where he could hang out with celebrities, take in shows and meet with publishers and civic leaders.” Or the offer of a lucrative nationwide speaking tour, postponed by his last campaign. Or his savvy use of the press during and after the Civil War to control his own version of events and advance his reputation. Mueller has thus written not only an articulate version of the Custer story but also a fresh interpretation of the multifaceted man who transcended the traditional perception of a soldier.

—C. Lee Noyes

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission.