In 1865 more than a dozen African-American volunteers in the Union army paid dearly for their role in “The Jacksonville Mutiny.”

On the morning of October 29, 1865, a little more than five months after the end of the Civil War, an African-American private in the Union army named Jacob Plowden stepped out of his tent at Camp Shaw in Jacksonville, Florida, to witness a horrific sight. On the parade ground, two white officers had tied a shirtless African-American soldier by his thumbs to a scaffold. The man was dangling in agony, the toes of his feet barely touching the ground as his thumbs were pulled away from their sockets.

The soldier’s alleged crime: stealing a jar of molasses from the commissary that morning.

Plowden lost his temper. An ex-slave from Tennessee in his mid-40s who had become a farmer in Pennsylvania before enlisting in the Union army in 1863, he was appalled to see black soldiers treated with the sort of brutality inflicted on slaves in the South. Two years earlier, Plowden had defied an order to help a white officer hang another black soldier by the thumbs, a common punishment during the Civil War, and as a result he had been demoted from corporal and spent 30 days in the brig on bread and water rations. But the experience didn’t deter him from taking action against such injustice. He roused his fellow soldiers in the 3rd Regiment of the U.S. Colored Troops, shouting that he’d rather die than see any more men go through the ordeal.

Soon, Plowden’s comrades—free blacks from the North as well as former slaves from the South—were watching in horror and outrage. “Let’s take him down,” Private John Miller shouted. “We are not going to have any more of tying men by their thumbs.”

Several dozen black soldiers advanced across the field toward the prisoner and the white officers, Lieutenant George Graybill and Lieutenant John L. Brower, the regiment’s commander. Brower was just 23 and had taken command only a few weeks before. What he lacked in experience, he tried to make up for with the severity of his discipline. But the soldiers’ defiance must have frightened him. When they got within five yards, Brower drew his revolver and fired several shots at them, wounding one man in the chest and arm.

“One of us is shot!” someone cried out. “Get your muskets. Shoot the son of a bitch!”

The soldiers ran back to their tents, quickly reemerged with their weapons, and began shooting at the white officers and others who came to their assistance. Brower was wounded in the thumb and collapsed in pain, one of many injuries suffered by participants on both sides in the melee. Rescuers carried him into the cookhouse for safety. Another white officer, who had slashed a black soldier with his sword, was hit in the head with a fence post. After brief but furious fighting, order was restored in the camp, and Plowden and others were arrested for what came to be known as the Jacksonville Mutiny.

A little more than two years before, in July 1863, these same African-American soldiers had gathered at Camp William Penn, outside Philadelphia, to hear a speech by abolitionist Frederick Douglass. Douglass, a former slave, still bore the scars on his back from a Maryland overseer’s whip. Many of the Union army volunteers who listened to him had suffered similar torments before escaping to the North. Now, they were willing to risk their hard-earned freedom by returning to the South to help end slavery. The 3rd USCT was one of 180 such black regiments, which collectively accounted for about 10 percent of the Union’s soldiers.

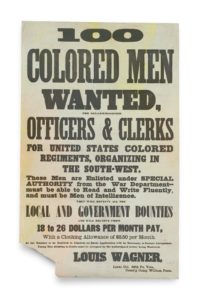

But Camp Penn itself was a reminder that the black troops weren’t entirely welcome in the North either. U.S. Army officials had erected the camp in Chelten Hills (today, Cheltenham Township) on the outskirts of Philadelphia rather than in the city, for fear that whites might riot to protest the presence of armed black men in their midst. There were plenty of signs of that tension. A black sentry at the camp was arrested for shooting and killing a white intruder, though he was later released. And at one point, the camp’s soldiers, under the watchful eyes of its sympathetic commander, German-born Louis Wagner, repelled and threatened to severely punish a slave catcher.

With notable exceptions, black soldiers fighting in Northern regiments certainly faced well-documented and varying degrees of discrimination from white superiors. Letters written by camp-based and frontline black soldiers to their families or friends and newspapers told of many heinous abuses—ranging from white officers sexually assaulting black women to the administration of torturous punishments that could lead to death. The soldiers also complained of inadequate medical treatment and said they received lower pay than whites.

With their training at Camp Penn completed, the 3rd USCT was sent to Morris Island, South Carolina. They dug trenches and built artillery platforms to assist in the siege of the Confederate stronghold Fort Wagner—an event that would be depicted in the 1989 motion picture Glory, which dramatized the fate of another African-American unit, the 54th Regiment of Massachusetts. The 3rd USCT’s noncombat duties were hard, dangerous work, with Confederate gunners shelling the trenches and sharpshooters trying to pick them off. Eventually, the fire grew so withering that they were forced to switch to working in the dead of night.

But the black troops persevered, and in September 1863 Confederate defenders finally abandoned the fort and fled. Corporal Henry Harmon was proud that the unit had helped to win the victory with their shovels—at a cost of 10 killed and more than 20 wounded, he reported. “In those trenches our men distinguished themselves for bravery and coolness, which required more nerve than the exciting bayonet charge,” he wrote in a letter home. “And sir, I am proud to say that I am a member of the 3rd United States Colored Troops, and I hope that I am not considered boasting when I say so.”

In early 1864 the men of the 3rd USCT boarded naval transports and sailed up the St. Johns River into Jacksonville, Florida, as part of a Union occupying force. They were stationed at Fort Shaw, a former Confederate base.

The black soldiers were clearly aware of tensions the occupation caused. Locals eyed them with suspicion, wondering if they were former Florida slaves who’d returned to inflict retribution. Their officers kept them under tight rein.

The soldiers soon got a shocking reminder of how perilous their situation was when three innocent men from the Massachusetts 55th USCT were arrested and charged with raping a white woman. After a hasty trial, the three were hanged. Some of the black troops sobbed as they watched the execution. Union general Truman Seymour showed up to give the rest of the black solders a warning. “Served them right,” he proclaimed. “Now let any other man try it if he dares.”

It didn’t help matters when Seymour led several other black units on an ill-advised raid to destroy a Confederate railroad trestle. The rebel forces lay in wait for them, and the Battle of Olustee ended in a Union defeat. Afterward, Seymour was relieved of his Florida command. At Olustee the men of the 3rd USCT could see other African-Americans being used as cannon fodder and undoubtedly heard the rumors that the Confederates had executed captured blacks on the battlefield.

It should have come as no surprise that these indignities and acts of violence, inflicted on honorable soldiers who were serving their country in time of war, culminated in the incident at Camp Shaw.

Two days after the “mutiny” in Jacksonville, guards escorted 15 soldiers from the 3rd USCT to the St. Mary, a Confederate side-wheel steamer that had been retrieved from a riverbed and refurbished by Union forces. The ship’s upper saloon was repurposed as a courtroom. The commander of the Union’s Florida forces, Major General John G. Foster, convened a jury that, incredibly, included some of the white officers who were tied to the debacle.

Perhaps sensing that the outcome was predetermined by racism, the black defendants waived their right to counsel and instead allowed the prosecutor, Judge Advocate A. A. Knight, to represent them as well. Knight’s nonaggressive questioning of Brower, the officer who had started the violence by shooting a black soldier, undoubtedly allowed him to escape any kind of reprimand or punishment. Shortly after Brower testified, the army hastily mustered him out and sent him home to New York.

In the end, all but one of the 15 defendants were convicted of various crimes. Six of them—Jacob Plowden, James Allen, David Craig, Joseph Green, Thomas Howard, and Joseph Nathaniel—were sentenced to death. The others convicted received prison sentences of up to 15 years.

Around noon on December 1, 1865, just days before they would have been mustered out of military service, the six condemned men were marched from the guardhouse at Fort Clinch in Fernandina Beach, Florida, to their place of execution. As the men walked past the crowd of spectators, Plowden saw a child and smiled. “Goodbye, my boy,” he said. Plowden had two young sons back home in Pennsylvania. He would never see them again.

The men were blindfolded and made to kneel in front of a row of caskets, with their backs to the 36-man firing squad, which came from another African-American unit, the 34th Regiment USCT. The executioners fired, and it was over.

The six men—the last servicemen to be executed for mutiny in the history of the U.S. Armed Forces—were buried in unmarked graves in the sand dunes. The site has since been swallowed by the Atlantic Ocean, just as the lives of the men of the 3rd USCT who rose up in the Jacksonville mutiny were swept away by racial animosity and injustice. In time, though, others would rise to take up the fight. MHQ

Donald Scott Sr. is the author of Camp William Penn: 1863–1865 (Schiffer Publishing, 2012).

[hr]

This article appears in the Autumn 2018 issue (Vol. 31, No. 1) of MHQ—The Quarterly Journal of Military History with the headline: Cruel and Not Unusual