|

| What Davis perhaps forgot was that the able-bodied male fugitives–sturdy workmen like these ex-slaves in Virginia– were serving as pioneers, carving a path for his corps. (National Archives) |

Brigadier General Jefferson C. Davis had few complaints about the able-bodied black men who were supplying the muscle and sweat to keep his Union XIV Corps on the move with Major General William T. Sherman’s 62,000-man army. The black ‘pioneers’ were making the sandy roads passable for heavy wagons and removing obstacles that Rebel troops had placed in his path. Davis was irritated, though, by the few thousand other black refugees following his force toward Georgia’s coast. He had been unable to shake them since the Union army stormed through Atlanta and other places in Georgia in late 1864, liberating them from their owners.

The army fed the pioneers in exchange for their labor. It also took care of the refugees who worked as teamsters, cooks, and servants. It did not, however, assume responsibility for the others. So every day, hundreds of black women, children, and older men wandered into the camps, begging for food. That was not so bad when forage was plentiful, but fall had turned to winter and the sandy soil closer to the ocean was not exactly fertile. Living well off the land was but a fond memory.

‘The rich, rolling uplands of the interior were left behind, and we descended into the low, flat sandy country that borders for perhaps a hundred miles upon the sea,’ recalled Captain Charles A. Hopkins of the 13th New Jersey Infantry. ‘…The country is largely filled with a magnificent growth of stately pines, their trunks free–for sixty or seventy feet–from all branches…. These pine woods, though beautiful, were not fertile and rations–particularly of breadstuffs–began to fail and had to be eked out [supplemented] by rice, of which we found large quantities; but also found it, with our lack of appliances, very difficult to hull.’

Besides exacerbating the food-shortage problem, the refugees tested Davis’s volatile temper by slowing down his march. Davis was eager to reach Savannah, the destination of Sherman’s 250-mile destructive ‘March to the Sea’ from Atlanta to Georgia’s coast. But at every step of the 25 miles left in Davis’s march, the XIV Corps would have to contend with Major General Joseph Wheeler’s Confederate cavalry corps, a constant hindrance and annoyance. Quicker movement would make it easier to evade the Rebel horseman as well as to defend against them.

So as Davis’s men approached the 165-feet-wide and 10-feet-deep swollen and icy Ebenezer Creek on December 3, the general envisioned more than merely another mass pontoon-bridge crossing. He saw an opportunity to rid himself of the refugees in a manner he thought would be subtle enough to elude censure. Controversy might follow, but he was used to that.

General Jefferson Davis, known to some by the derisive nickname ‘General Reb’ because of his name, was a veteran Regular Army soldier who loved battle. Short-tempered and a proficient cusser, he had a nasty reputation and was infamous in his time for a furious, short-lived feud with Union Major General William Nelson. In August 1862 Nelson and Davis had got into a heated argument over the defense of Louisville, Kentucky, where Nelson was in command. Nelson ordered Davis, a brigadier general, to leave. The two men met again a few weeks later in a Cincinnati hotel. Davis demanded an apology from his superior, and Nelson stubbornly refused to give him one. Minutes later the angry brigadier shot and killed the major general at point-blank range. Davis was arrested but later released. Though plenty of questions went unanswered, no charges were ever filed against him.

As the XIV Corps prepared to cross Ebenezer Creek, Davis ordered that the refugees be held back, ostensibly ‘for their own safety’ because Wheeler’s horsemen would contest the advance. ‘On the pretense that there was likely to be fighting in front, the negroes were told not to go upon the pontoon bridge until all the troops and wagons were over,’ explained Colonel Charles D. Kerr of the 126th Illinois Cavalry, which was at the rear of the XIV Corps.

‘A guard was detailed to enforce the order, ‘ Kerr recalled. ‘But, patient and docile as the negroes always were, the guard was really unnecessary.’

Though what happened once Davis’s troops had all crossed remains in dispute, it seems fairly certain that Davis had the pontoon bridge dismantled immediately, leaving the refugees stranded on the creek’s far bank. Kerr wrote that as soon as the Federals reached their destination, ‘orders were given to the engineers to take up the pontoons and not let a negro cross.’

‘The order was obeyed to the letter,’ he continued. ‘I sat upon my horse then and witnessed a scene the like of which I pray my eyes may never see again.’

How many women, children, and older men were stranded cannot be determined precisely, but 5,000 is a conservative estimate. ‘The great number of refugees that followed us…could be counted almost by the tens of thousands,’ Captain Hopkins of New Jersey guessed. Major General Oliver O. Howard, commander of the right wing of Sherman’s army (which included Davis’s corps), recalled seeing ‘throngs of escaping slaves’ of all types, ‘from the baby in arms to the old negro hobbling painfully along the line of march; negroes of all sizes, in all sorts of patched costumes, with carts and broken-down horses and mules to match.’ Because the able-bodied refugees were up front working in the pioneer corps, most of those stranded would have been women, children, and old men.

What happened next strongly suggests that Davis did not have the refugees’ best interest in mind when he delayed their crossing of the creek, to say nothing of his apparently having ordered that the bridge promptly be dismantled. Davis’s unabashed support of slavery definitely does not help his case, though Sherman insisted his brigadier bore no ‘hostility to the negro.’

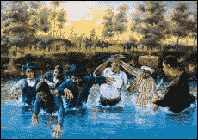

|

|

Painting by Dave Russell

|

Kerr saw Wheeler’s cavalry ‘closely pressing’ the refugees from the rear. Unarmed and helpless, the former slaves ‘raised their hands and implored from the corps commander the protection they had been promised,’ Kerr wrote. ‘…[but] the prayer was in vain and, with cries of anguish and despair, men, women and children rushed by hundreds into the turbid stream and many were drowned before our eyes.’

Then there were the refugees who stood their ground. ‘From what we learned afterwards of those who remained upon the land,’ Kerr continued, ‘their fate at the hands of Wheeler’s troops was scarcely to be preferred.’ The refugees not shot or slashed to death were most likely returned to their masters and slavery.

Kerr’s descriptions of the atrocity apparently met widespread skepticism, and he was forced to defend his integrity. ‘I speak of what I saw with my own eyes, not those of another,’ he asserted, ‘and no writer who was not upon the ground can gloss the matter over for me.’ Still, he left it to another officer, Major James A. Connolly of Illinois, to blow the whistle on Davis. ‘I wrote out a rough draft of a letter today relative to General Davis’ treatment of the negroes at Ebenezer Creek,’ Connolly wrote two weeks after the incident. ‘I want the matter to get before the Military Committee of the Senate. It may give them some light in regard to the propriety of confirming him as Brevet Major General. I am not certain yet who I had better send it to.’

Connolly decided to send the letter to his congressman, who evidently leaked it to the press. Secretary of War Edwin M. Stanton reacted to the subsequent bad publicity by steaming down to Savannah, which Sherman’s army had captured on December 21, to investigate the matter. Stanton did not preannounce his visit, but Sherman had received advance notice about it from President Abraham Lincoln’s chief-of-staff, Major General Henry W. Halleck. ‘They say that you have manifested an almost criminal dislike to the negro…, [that] you drove them from your ranks, preventing their following you by cutting the bridges in your rear and thus caused the massacre of large numbers by Wheeler’s cavalry,’ Halleck wrote.

Stanton arrived on January 11 and began asking questions. ‘Stanton inquired particularly about General Jeff. C. Davis, who he said was a Democrat and hostile to the negro,’ Sherman later wrote. Stanton showed Sherman a newspaper account of the affair and demanded an explanation. Sherman urged the secretary not to jump to conclusions and, in his postwar memoirs, reported that he ‘explained the matter to [Stanton’s] entire satisfaction.’ He went on to say that Stanton had come to Savannah mainly because of pressure from abolitionist Radical Republicans. ‘We all felt sympathy…for those poor negroes…,’ Sherman wrote, ‘but a sympathy of a different sort from that of Mr. Stanton, which was not of pure humanity but of politics.’

Sherman’s attitude toward black people is perhaps best illustrated in his own words, in a private letter he wrote to his wife, Ellen, shortly before he left Savannah to continue his march up the coast. ‘Mr. Stanton has been here and is cured of that negro nonsense,’ he wrote. ‘[Secretary of the Treasury Salmon P.] Chase and others have written to me to modify my opinions, but you know I cannot, for if I attempt the part of a hypocrite it would break out in every sentence. I want soldiers made of the best bone and muscle in the land, and won’t attempt military feats with doubtful materials.’ As he admitted in his memoirs, ‘In our army we had no negro soldiers and, as a rule, we preferred white soldiers.’

‘The negro question was beginning to loom up…and many foresaw that not only would the slaves secure their freedom, but that they would also have votes,’ his memoirs further reveal. ‘I did not dream of such a result then, but knew that slavery, as such, was dead forever; [yet I] did not suppose that the former slaves would be suddenly, without preparation, manufactured into voters–equal to all others, politically and socially.’

In course, when considering Sherman and his actions, it’s important to remember that his ideas about black people, though shocking today, were hardly unique in his time. The majority of Union volunteers, and of Northerners in general, were at most ambivalent about emancipation and were vehemently opposed to black suffrage.

Given the prevailing beliefs of the time, it might be no surprise that Union authorities justified the incident at Ebenezer Creek as a ‘military necessity.’ None of the officers involved was even officially reprimanded. Most of them advanced in their military and, later, civilian careers.

Davis’s commander, Howard, who had been described as ‘the most Christian gentleman in the Union army,’ went on to found Howard University, a black college in Washington, D.C. He also became the first director of the Freedmen’s Bureau, which the Federal government set up to help the recently freed slaves make the transition from slave to citizen.

Wheeler’s cavalry was roundly condemned for its part in the affair, but the reputation of its young commander was evidently not harmed. Wheeler went on to serve in the U.S. House of Representatives from 1885 to 1900 and as a major general of volunteers in the Spanish-American War in 1898.

Davis handled the Ebenezer Creek commotion with the same coolness that had taken him back to battlefield command so soon after the Nelson shooting. Again he was never punished or even reprimanded. In fact, he was later made a brevet major general.

Then there is William T. Sherman, the field commander ultimately responsible for Davis’s actions. Sherman was rewarded with the Thanks of Congress for the revolutionary ‘total war’ he waged during his March to the Sea. At the May 1865 Grand Review of the Armies, the huge parade through Washington, D.C., to celebrate Union victory, Sherman was hailed as a war hero. A few years later, newly elected President Ulysses S. Grant made Sherman a full general and general-in-chief of the U.S. Army.

Sometime during those postwar years, Sherman offered a rosy recollection of the reception he and his men had received as they marched through Georgia. ‘…the Negroes were simply frantic with joy,’ he said. ‘Whenever they heard my name, they clustered about my horse, shouted and prayed in their peculiar style, which had a natural eloquence that would have moved a stone.’ Apparently, though, it did not move Sherman deeply enough to make him seek justice for the soon-forgotten victims of the Ebenezer Creek incident.

This article was written by Edward M. Churchill and originally published in Civil War Times Magazine in October 1998.

For more great articles, be sure to subscribe to Civil War Times magazine today!