With two engines out and a fire in the bomb bay, the battered B-17’s odds of survival didn’t look good, but somehow the three remaining crewmen kept the shot-up bomber flying.

“Brakes,”ordered First Lieutenant Edward S. Michael, pilot of the B-17G Bertie Lee. “Brakes set,” answered First Lieutenant Franklin Westberg, his copilot. Continuing down the takeoff checklist, the experienced pilot took nothing for granted. Finally, pushing the throttles forward, Michael applied rudder to keep the big bomber in the runway’s center until they lifted off. “Gear up,” he ordered. Forming up with the rest of the 364th Bombardment Squadron Flying Fortresses of the 305th Bombardment Group (Heavy), Bertie Lee headed east across the English Channel. It was April 11, 1944, and Stettin, Germany—75 miles beyond Berlin—was their target.

During the Eighth Air Force’s darkest days in 1943, when bombers were being shot out of the sky with frightening rapidity, if a B-17 survived 25 combat missions, its crew rotated Stateside. Bertie Lee’s crew had already completed 25 sorties by April 1944, but bad timing and a command decision by Lt. Gen. Jimmy Doolittle conspired to send them into harm’s way once more on the 11th. Doolittle was concerned that by rotating his best aircrews home after 25 combat missions, he was losing them just when he needed them most, so he had recently upped the number of required missions to 30. Experienced crews like Bertie Lee’s, which had already logged close to the original rotation number, now had to fly 27 missions before returning home.

It was a very unpopular policy, but Doolittle had his reasons. Raids on enemy positions along the Channel coast had become more frequent in preparation for D-Day, and those, along with bombing missions in France’s interior, had recently proved less dangerous for aircrews. P-51 Mustangs equipped with drop tanks now escorted the bombers deep into Germany. Doolittle had given the fighter pilots permission to go after targets of opportunity once the bombers had dropped their ordnance, a change that put great pressure on Germany’s fighter command. Luftwaffe pilots now had to watch the sky even when they were on the ground. Doolittle had stolen a play from Civil War Lt. Gen. Ulysses S. Grant’s strategy book: Attack, attack and then attack again. When you had more assets and a better supply chain, a war of attrition worked in your favor.

Bertie Lee’s crew of 10 included seven men on their 26th mission and three replacements on their first flight. Besides Michael and Westberg, the other officers were navigator 2nd Lt. M.M. Calvert—on his first mission—and bombardier 2nd Lt. John Lieber. The remainder of the crew consisted of enlisted men: Staff Sgt. Jewell Phillips, flight engineer; Staff Sgt. Reynold Evans, radio operator; Staff Sgts. Anthony Russo and Arthur Kosino, waist gunners; Staff Sgt. Clarence Luce, tail gunner; and Staff Sgt. Fred Wilkins, in the bottom ball turret. Of these, Luce and Phillips were participating in their first raid. Four hours into the mission, the formation started taking flak. As black puffs of smoke filled the sky, Bertie Lee was hit in the right wing, sending a shudder through the bomber.

The B-17’s gunners could see German fighters working over a flight of B-24s in the distance. While the B-24 Liberator was a good long-range bomber, it could not take as much punishment as a Flying Fortress and had a tendency to burn when hit. Flashing through the formation, the German fighters sent 13 B-24s spiraling toward earth. Tracer rounds slicing across the sky, smoke from burning bombers and an occasional parachute opening amid the flak testified to the carnage surrounding them.

As Bertie Lee and its sister ships hit the IP for the run on Stettin’s ball bearing plant, the enemy threw an old trick at them. More than 100 Messerschmitt and Focke-Wulf fighters had massed high above the bomber formation, poised for an ambush. Despite the Americans’ fighter escort and intense flak from their own anti-aircraft guns, the German fighters suddenly swooped down like birds of prey, sending one B-17 plunging to the ground and badly damaging another.

Many of the fighters seemed to be concentrating on Bertie Lee, raking the Fortress from nose to tail with 20mm rounds. Every crewman with a machine gun at hand returned fire. Enemy cannons knocked out two of the bomber’s engines and badly shot up the top turret. The radio room also took a beating from shell fragments, shredding Sergeant Evans’ parachute stored there. Cannon fire destroyed most of Bertie Lee’s flight instrumentation, blew out a cockpit window and injured both the pilot and copilot, with Michael suffering a gaping thigh wound.

Suddenly the bomber shuddered and started to spin earthward— even as the fighters continued to fire on it. Hydraulic fluid streamed down the windscreen, making it nearly impossible to see ahead, and the cockpit began to fill with smoke. At first the controls refused to respond, but Michael and Westberg managed to wrestle the stricken bomber into level flight after losing 3,000 feet of altitude.

Even then, the enemy fighters hadn’t given up their pursuit. Three 20mm cannon shells now hit Bertie Lee’s bomb bay, setting fire to three of the 42 100-pound incendiary bombs stored there. Evans staggered to the cockpit and alerted Michael. They all realized that the bomber could explode at any moment. Michael tried to use the emergency jettison switch to drop the bombs, but it wouldn’t function.

“Bail out, bail out, bail out!” Michael shouted over the intercom, and the bail-out buzzer clanged its warning to the beleaguered crew. Two of the new men were the first to escape. In the tail gun, Sergeant Luce opened his trap door and slipped out. Lieutenant Calvert, the navigator, went next. Gunners Russo, Wilkins and Kosino had snapped their parachutes into their harnesses and were preparing to jump when Evans ran back and begged them to not leave him behind without a usable parachute. At first Kosino tried to rig his own harness so they both could use one parachute, but then someone discovered an extra chute stored in a duffel bag. The four enlisted men leapt out above Germany, headed for certain capture.

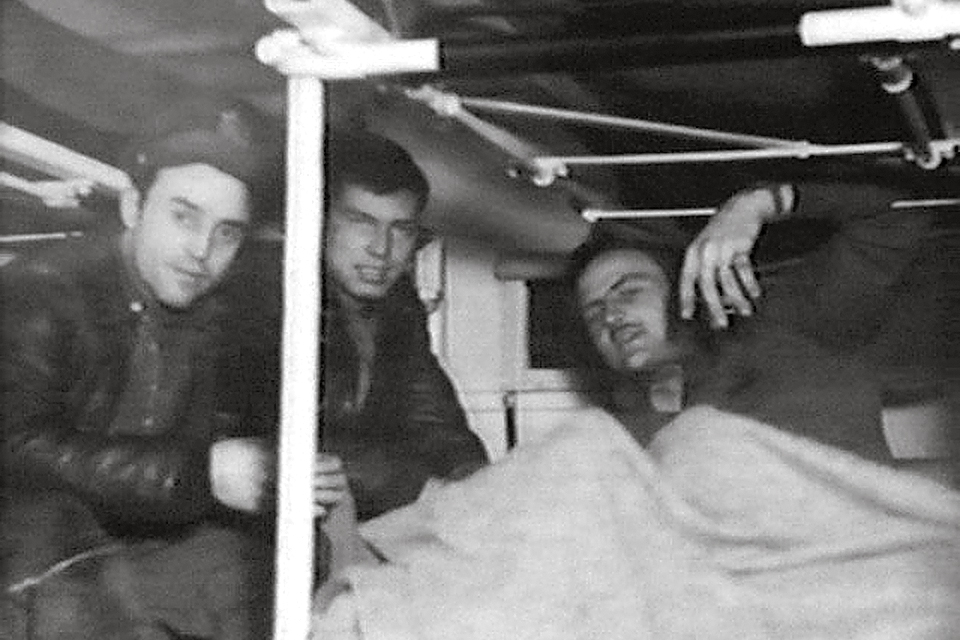

Believing the aircraft was empty, the pilots began preparing to jump as well at that point. But then the German fighters returned to the attack, and Michael spent precious moments steering the B-17 into a cloud bank in an attempt to escape. At that point Sergeant Phillips appeared in the cockpit, with a shattered arm and badly wounded eye. The sergeant was unable to put on his parachute or open it due to his injuries, so Michael attached Phillips’ parachute to his harness, led him to the door and pulled the ripcord as the flight engineer jumped from the bomber.

Michael turned back to the cockpit, where Westberg remained at the controls. Just then they heard one of Bertie Lee’s machine guns firing. Lieutenant Lieber, the bombardier, had missed the bail-out command and remained at his station. Incredibly, despite the mayhem all around him, he continued to fight the enemy. Michael, by now bleeding profusely, ordered Lieber to put on his parachute and get out. When the bombardier reached for his chute, however, he discovered that it had also been riddled by German fire. The pilot ordered Lieber to take his own parachute, but the plucky bombardier refused—and went right back to firing his gun. Recognizing the inevitable, Michael told him to get back to the bomb bay and try to find some way to drop the incendiary bombs before they exploded.

Somehow Lieber managed to release the bombload. Meanwhile, the Germans continued their attacks, forcing Michael to fly violent evasive maneuvers. By this time the wounded bomber had been under constant attack for 45 minutes, and it was still flying on just two engines. The injured pilot managed to shake the fighters by dodging into a cloud bank once again, but when he reemerged he had to contend with heavy, accurate flak.

Convinced that their best option would be to crash-land, Michael took the B-17 down to treetop level. Blood was pooling on the cockpit floor beneath his wounded leg, and he began to feel dizzy. The rapid dive to the deck shook off the German fighters, but the flak towers were still spitting anti-aircraft fire at the low and slow Bertie Lee.

Keeping the B-17 just 50 feet above the ground, Michael headed toward England. By some miracle, the battered bomber continued to fly. A windshield had been shot away, two engines were out, the instrument panel was wrecked and the control cables, right wing, rudder and elevators had all sustained damage. On top of that, the airframe’s integrity was threatened by a huge hole created by the burning incendiary bombs. The three remaining crewmen knew their plane could snap in two at any time. Moreover, the bomb bay doors refused to close, adding significant drag to the struggling Fortress.

Westberg now took over the controls while Lieber administered first aid to the badly wounded pilot. Michael continued to fly the B-17 while he was conscious, but as he lost more blood he began blacking out, at which point the copilot would take over. Lieber stayed in the cockpit serving as a medic, trying to keep both pilots patched together so that they could keep the bomber in the air.

Bertie Lee flew so low across Holland that as the bomber roared by the crewmen could see the faces of farmers waving at them from their fields. Some of the Dutch onlookers even pointed the way toward England. Then the North Sea came into view, and the Fortress was suddenly out over the water, with Michael flying. When the pilot once again lost consciousness, Westberg turned the stricken bomber for home, fighting hard to keep the aircraft above the waves. Sluggish and unresponsive, it didn’t have much life left. Lieber continued to work on Michael, trying to keep him awake.

At last the English coastline came into view, and Westberg pointed the B-17 toward the RAF airfield at Grimsby. With no working radio to alert the airfield, he circled while Lieber shot flares out of the plane, to let the tower know they’d be making an emergency landing with wounded on board. Westberg again shook Michael awake, this time for the final approach. With no undercarriage, no flaps, no rudder, no airspeed indicator and no altimeter, the landing promised to be as dangerous as their entire flight back to England. Michael gave one more order, telling the other two to bail out with the remaining good parachutes and that he would land the B-17 alone. But Westberg and Lieber refused to comply.

Michael then started his landing approach, knowing the bomb bay doors were stuck open and the lower ball turret’s guns frozen down—hardly a good posture for a belly landing. It seemed likely that the hole in the airframe would cause the B-17 to crack in two from the stress of the landing. But despite the severe damage to the control surfaces and with no indications of his height or airspeed, Michael somehow managed to perform a perfect landing, considering the circumstances. An ambulance quickly carted the three Americans to the hospital.

Bertie Lee had flown its final mission. Michael had named the bomber after a girl he met in flight school, whom he would eventually marry. Now the battered B-17 was declared unfit even for spare parts. Bertie Lee was reduced to scrap metal—an ignoble end for a gallant flying machine that had brought its crew home against all odds.

Michael required several transfusions, but after a couple of days his condition improved and his thoughts began to clear. During the seven weeks he remained in the hospital, however, he became wracked with survivor’s guilt. Not even Lieber and Westberg’s visits could sweep away the pilot’s feelings of failure. While the 305th Bomb Group considered him a hero, Michael regarded himself as a commander who had lost seven good men. After all, he had given the order to bail out of a ship that ultimately made it home. He wondered what had happened to those men.

Michael grew a goatee as he lay in bed recovering from his wounds, and he resolved that he would not shave until he found out what had happened to every man in his crew. In effect, his nonregulation facial hair would serve as a reminder of urgent unfinished business.

By July 1944, Michael had returned to limited duty in the U.S. The 305th had nominated him for the Medal of Honor, but an officer sporting a goatee became a matter of consternation to his superiors.

By that time, too, news had begun filtering in regarding the fate of Bertie Lee’s crew. Art Kosino, Reynold Evans, Fred Wilkins, Anthony Russo and Clarence Luce were imprisoned at Stalag 17-B, near Krems, Austria. Lieutenant Calvert was being held at a separate prison for officers. Only the fate of Staff Sgt. Jewell Phillips, whom Michael had helped to jump from Bertie Lee, was still unknown.

On January 10, 1945, the morning of his award presentation, Michael still had not shaved, though he’d been increasingly pressured to do so. Rather than force the issue, the Army brass had wisely opted for another path: finding Sergeant Phillips. As Michael was preparing his uniform for the ceremony, a messenger arrived and advised him that the Army had at last found the flight engineer. Phillips had been so severely wounded that the Germans did not believe he could survive captivity, and had instead repatriated him.

With this welcome news, Michael shaved off his beard.

Later that morning President Franklin D. Roosevelt presented 1st Lt. Edward S. Michael the Medal of Honor and shook his hand. The saga of Bertie Lee’s last flight had finally come to an end.

Previous contributor David F. Crosby is the author of A Guide to Airborne Weapons. He is currently working on a book about al-Qaeda. Additional reading: Above and Beyond: The Aviation Medals of Honor, by Barrett Till man. Also see homeofheroes.com.

Originally published in the September 2013 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.