A SMALL PERFUME BOTTLE dyed green and labeled Belle Haleine, Eau De Voilette—“Beautiful Breath, Veil Water”—by iconoclastic artist Marcel Duchamp sold at auction at Christie’s in 2009 for $11,489,968. The title Duchamp gave this enigmatic objet is believed to allude to Belle Da Costa Greene, an imperious figure who ran J.P. Morgan’s library, a few steps down Madison Avenue from the financier’s former Manhattan residence.=

Fresh off the boat from France in 1915, Duchamp had needed money; a mutual acquaintance put him onto Greene, who in her capacity as Morgan’s librarian hired the new arrival as a translator. Greene let Duchamp go after six weeks, a period during which Greene doubtless

irked and intrigued the artist, as she did so many others. The bottle originally held a Rigaud brand perfume, Un air embaumé, and was made of peach-colored glass. Duchamp dyed the container green, perhaps an allusion to the Belle Da Costa Greene story as well as a play on her family name. Aficionados (see “Decoding Duchamp,” below) argue that in creating the work Duchamp was encoding references to his temporary patroness. The artist used the piece as an element on the cover of the only issue of the modernist magazine New York DADA, produced in collaboration with the versatile, innovative American artist Man Ray in 1921. He did not display the work until 1965, 15 years after Greene died.

Duchamp was among a circle of artists and scholars acquainted with the green-eyed Greene, who for her time lived the fast life. She dressed and behaved flamboyantly—drinking and smoking, traveling solo, enjoying numerous suitors, and conducting an affair with a married man. Greene had entered Morgan’s orbit in 1905 through the banker’s nephew, Junius Morgan, an acquaintance from her job. Greene and the younger Morgan, both bibliophiles, worked at the Princeton University Library in New Jersey. Introduced by Junius, Greene, who was 26 but claimed to be 23, hit it off with the 64-year-old tycoon. Morgan hired her as a librarian, in which role she not only oversaw and curated his burgeoning collection of antiquities but ran personal interference for and read aloud to “Big Chief,” as she called the Wall Street dynamo. Asked later if she had been one of Morgan’s many mistresses, Greene would laugh and say, “We tried.”

Feted for her professional acumen, wit, and style, Belle Da Costa Greene lived a life of self-invention, propelled by drive and audacity. She came of age at a time of particular poignancy, in her own life and in the nation’s, rising to a position of power and personal satisfaction rare for a woman of that time—or any time. Fortune brought her into contact with Junius Morgan; preparation readied her to wow his plutocrat uncle. The rest was Belle Greene’s doing. She survived two world wars and a depression, shepherding the Morgan Library for decades following its namesake’s death in 1913. Her secret, like Duchamp’s bottle, lay in the packaging.

College Try

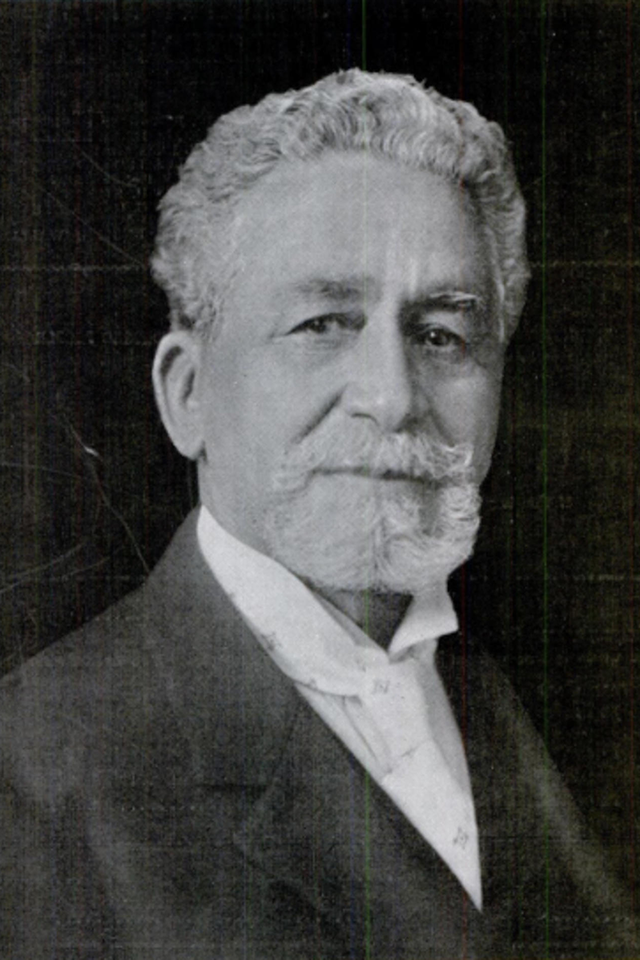

Four decades before the youthful Belle arrived at the Morgan Library, Richard Greener, an African-American born in Boston in 1844 to free black parents, was trying to get into college. His paternal grandfather was an African-American schoolteacher; his maternal grandfather was Spanish, from Puerto Rico. A ravenous reader, the youth, whose skin tone bespoke his mixed ancestry, took classes at

Oberlin College and Dartmouth College and spent senior year at Phillips Andover Academy in Andover, Massachusetts, that elite school’s first black student. Mentors helped him gain admission to Harvard University, from which he graduated in 1870, another African-American first. Greener’s thesis, on Irish land tenancy, won that year’s Bowdoin Prize.

Upon graduation Greener moved to Philadelphia, where he became principal of a school. In that capacity he was part of a delegation that traveled to Washington, DC, to lobby President Ulysses S. Grant for a federal civil rights law. He and Grant became acquainted, and he also met and married Genevieve Ida Fleet, born into a well-educated, musically inclined, and light-skinned family of free blacks. In 1873, Greener accepted a professorship at the University of South Carolina at Columbia, which was integrating under Reconstruction-era federal oversight. Greener, the institution’s first African-American faculty member, taught, tutored under-prepared black students in Greek, Latin, math, philosophy, and logic, organized the university library, and earned a degree from the law school. He was so avid a book lover that he assembled a personal collection of African-Americana, including a copy of Benjamin Banneker’s 1792 Almanac. In 1876 he submitted a paper on “Rare and Curious Books” to the American Philological Association, to which he belonged.

In late 1876 the government began to withdraw federal troops from the South. By 1877 white supremacists again controlled South Carolina state institutions, driving blacks out of positions of influence. Greener moved Genevieve and their two children back to Washington, then to New York City, where he practiced law, wrote, and was a Republican activist. He managed the organization assigned to build a memorial to Ulysses Grant. His work required much travel, which along with other stresses shredded his marriage. By 1897, Greener was listing his address as his New York office; in 1898, he and Genevieve, now parents to five, separated formally. They never divorced. To support her offspring, Genevieve Greener taught music. New York lacking an official definition of race, she and her children apparently identified—and were identified by others—as white.

The fourth Greener child, Belle, received some training in library science. Heidi Ardizzone, author of a 2007 Belle Greene biography, An Illuminated Life, found Greener’s name on a list of students enrolled in a bibliography class at Amherst College’s Fletcher Summer Library School. Belle Greener also may have attended Teachers College at Columbia University. By the time Richard Greener’s olive-skinned daughter was applying for a job with Princeton University’s library in 1901, however, “Belle Greener” had vanished, replaced by “Belle Da Costa Greene.” She and her siblings had all plugged “Da Costa” into their names; should anyone remark on her complexion, Belle mentioned Portuguese ancestry.

Greene’s literary and artistic background may have produced the addition. In 1515 Flemish illuminator Simon Bening had created his masterpiece “Da Costa Hours” for a Portuguese family. The name means “of the coast,” implying borders between land and sea, fact and fiction, black and white, wealth and poverty.

It Girl

White Belle Greene had options unavailable to black Belle Greener, especially in segregated Princeton, New Jersey. Hiring on at the university library, Greene roomed during the work week with a Princeton family; biographer Ardizzone suspects Greene’s hosts, who also had a library connection, may have been passing as well. Weekends Belle lived with her mother in an apartment on West 122nd Street near Columbia University on Manhattan’s Morningside Heights, an address Greene kept for years, even after going to work for Morgan.

From the start of her career with Morgan in 1906, Greene was an arts-and-lit “it girl.” Her love of fashion and flamboyance attracted

invitations to sit for artists. Favoring fashionable gowns and pearls, she liked to say, “I am a librarian, but I don’t have to dress like one.”

Photographs and sketches abound that show her appearing cool, composed, and self-aware. Magazines featured the luminous, green-eyed gamine. As J. P. Morgan’s librarian, Greene commanded the cantankerous banker’s campaign to assemble a collection of artworks, books, and other antiquities he hungered for. She shared Morgan’s passion for medieval European art, particularly illuminated manuscripts. To advance the cause, she cultivated contacts and experts. She traveled to Europe, working her way into artistic and literary circles. She haggled. At least once, she smuggled. In 1910, the library acquired “Da Costa Hours.”

Greene could scarcely have landed in a more public, yet protected spot. In 1902 Morgan, a voracious collector of all kinds of art, had hired star architect Charles McKim to design a library adjacent to his home at Madison and 36th Street. Four years later, the magnificent result resembled a three-room palazzo of Renaissance Italy, with vaulted ceilings and two stories of glass-front bookcases to protect Morgan’s treasures. Greene told Morgan she wanted his library to be “preeminent,” hoping someday to outdo the British Museum and France’s Bibliothéque Nationale. Within two decades the Morgan collection comprised more than 46 illuminated manuscripts and nearly 5,000 books, as well as etchings and drawings. Morgan favored early European works and antiquities, but he also had corralled domestic

treasures such as the diaries of Henry Thoreau and Nathaniel Hawthorne.

Friends in Need

Among Greene’s intimates was Bernard Berenson, a prominent art critic, appraiser, and philandering husband who spent most of his time in Italy and London. For years Greene and Berenson sustained an intense relationship, first as master and apprentice, becoming lovers in 1908, and ending as platonic friends. Greene burned Berenson’s letters to her, but Mary Smith Berenson, who tolerated her husband’s affairs, preserved correspondence to him, including Greene’s—a kaleidoscopic showcase of an extravagant personality that really deserves a reading in full. In 1909, Greene wrote, “I wonder if any living being has greater imaginative powers than I.” From a 1910 letter: “My fate is bound round my neck in bonds of iron, rather gold, glittering gold and locked with the Eternal $.” Greene never wrote about race and only seldom mentioned blacks; when she did, it was with an arch dismissiveness. Between the lines wavers a sense that the relationship soured after Berenson impregnated her, apparently resolved in England by an abortion—a procedure not readily available in the United States.

Berenson had his own identity issues. Born a Jew named Bernhard Valvrojenski in Lithuania in 1865, he was 10 when his family emigrated to Boston and changed its name and 20 when he was baptized an Episcopalian. Educated at Harvard, he lived his life as a Christian or secular European. Berenson and Greene remained in close contact throughout her more than three decades with the library.

No evidence exists that Greene discussed her ancestry with Berenson, although she did allude to gossip about herself, including other less than surreptitious romances. “I really had to laugh at your last letter complaining of all the scandal you were hearing about me—I suppose they say everything…but what difference does it make?” she wrote. “I’ve come to the conclusion that I really must be grudgingly admitted the most interesting person in New York, for it is all they seem to talk about—.” The endlessly jealous Berenson, consumed with cupidity and curiosity, guessed to friends that his paramour had Malay blood. In a 1909 letter to Berenson, Boston art patron and client Isabella Stewart Gardner hinted at Greene’s racial background, urging Berenson not to bruit her musings about. Decades later, speculation surrounding Greene still was percolating through a 1934 letter from a bookseller to Princeton librarian M.L. Parrish:

“Miss Bella [sic] da Costa Greene is fortyish with brown hair and wears horn-rimmed spectacles. My first impression of her was that she looked bloated as if she had a touch of dropsy or perhaps drank too much, although she is not overly heavy and still not thin. She has a bulbous nose (perhaps caught from the numerous photographs of her patron, many of which hang, stand and lie about her office) and her skin must be very swarthy, for, she wore white powder which made her look kind of speckled gray, like the negro you see pouring dusty cement into the mixers on building construction jobs. She was dressed in a sort of classic garment of black velvet relieved here and there by bits of chartreuse lace. She has short, stubby fingers and chews her nails—to the quick.”

J.P. Morgan died in 1913. Greene fretted that son and heir Jack would abandon the library. She lobbied him to keep the operation going—and succeeded in building a close, jesting relationship. In 1924, for example, she writes, “In regard to the Tennyson items, which personally I loathe, it is a question of perfecting your already very large and fine collection of imbecilities.” To which Morgan replies, “I reluctantly confirm that we ought to have the Tennyson idiocies.”

Greene ran the Morgan Library the rest of her life, not only organizing and constantly enlarging the collection but also directing its exhibitions and lecture programs. Her late employer had left her $50,000—today, $1.27 million. That largess enabled her to buy and combine two apartments into a residence for herself and her mother on 40th Street in Manhattan’s Murray Hill neighborhood, a few blocks from the Morgan Library. The inheritance an

d her library salary helped her and her family navigate Depression-era America.

All but one of Greene’s four siblings remained close by in New York. Nephew Robert—son of younger sister Theodora Genevieve, known as “Teddy”—had joined Belle’s household after his mother married for a second time in 1921. Belle became the youth’s legal guardian. Serving in the European theater during World War II, Robert committed suicide. That same year, Greene faced another crisis when Jack Morgan died unexpectedly of a stroke. She feared for the library’s future but her second patron had planned for his father’s creation to continue as a public institution, and Greene oversaw its shift in status and the appointment of her successor.

Over her 40-year career, Belle Greene achieved celebrity without revealing herself. Richard Greener, who never shied from revealing himself, passed nearly unnoticed into history.

In Exile

Long after leaving the Palmetto State, Richard Greener referred to himself as a “South Carolinian in exile,” suggesting how he must have thrilled to the freedom and possibility of his years there before bigotry renewed itself. Back in Washington, DC, with his wife and their

children, Greener worked as a lawyer and dean of Howard University Law School. In 1881, he collaborated on legal appeals by the first two West Point cadets of African descent, Henry Ossian Flipper and Johnson Chesnut Whittaker—high-profile cases that involved false accusations of embezzlement and self-mutilation shot through with racism and expressive of the limits of legal redress then available to African-Americans. Upon Ulysses Grant’s death in 1885, a commission formed to build a monument to the hero and former president. That body, whose membership included J. P. Morgan, invited Greener to become the commission’s only African-American participant and to manage day-to-day operations. The Greeners moved to New York City.

Greener was prominent enough in the black community to draw criticism for the comfort he displayed interacting with white elites; similarly, the ease with which Genevieve Greener and their children mingled with Caucasians had tongues wagging. Richard Greener did not shy from the spotlight aimed at black activists. He was paid for speaking engagements, including debates with Frederick Douglass, who was much his senior. Greener endorsed racial pride.

“The Negro in America was not to lose his identity by absorbing with the dominant race, but to endeavor to do something as a Negro,” Greener said in 1877. He wrote trenchantly on the topic. In “The White Problem,” an 1894 essay in the Cleveland Gazette, an African-American newspaper, he argued that blacks had established a decisive record of accomplishment and service, only to find their way barred by white resistance: “If character, reputation, manly accomplishments, the heights reached, the palm won, still find any black hero a `marked man,’ because of no fault of his own, and church and society, home and club, united in thus ostracizing him and his children, then is it not demonstrated that it is not the Black but the White Problem, which needs most serious attention in this country?”

Painful experiences

Greener was speaking and writing from painful experience. His multiple degrees and many achievements had been no guarantors of income. His support of causes as diverse as Irish independence and women’s suffrage put him at odds with the more cautious Booker T. Washington, who seemed never to support Greener and who in fact may have undermined the other man’s opportunities.

Greener’s constant struggle to support his family figured in his and his wife’s 1897 separation. Their children remained with her; he announced he would support them only to age 18. In 1898, in another first for his race, Richard Greener accepted a position as a U.S. government commercial agent. He was stationed at Vladivostok, Siberia.

Around the time her father was moving out of the family home, college student Belle was, with her siblings and mother, living in Manhattan on West 99th Street, a white neighborhood, shortening the family name, and, in the 1890/1900 census, identifying as white—a declaration that may have been easier in New York City, whose population at the time was less than 2 percent black. In this switch, the Greeners/Greenes were not alone in the United States. Between 1910 and 1920, 400,000 Americans of mixed racial background nationwide disappeared from census rolls.

In Russia, Greener began a second family with a Japanese woman. Explanations vary as to why he returned to the United States in 1905,

according to Katharine Reynolds Chaddock, author of the only Greener biography, 2017’s Uncompromising Activist. The formerly high-profile figure, likely isolated by education and personal intensity, now had less interest in activism, although he offered to mediate between Booker T. Washington’s accommodationists and a harder-line wing led by W.E.B. DuBois. Greener helped draft the 1909 statement that led to the establishment of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People. “I have never aspired to be a leader,” the frequent pioneer said. “I still believe and preach the doctrine that each man who raises himself elevates the race.”

Greener spent his final years living near the University of Chicago with three female cousins and working as a lawyer, lecturer, and newspaper essayist. He died in 1922 at age 78, his reputation gradually dimmed until 2014, when a cache of his diplomas and business documents turned up in an attic in one of the poorest neighborhoods on Chicago’s South Side. Harvard and the University of South Carolina acquired the materials and subsequently honored him—Harvard with a portrait in the Annenberg Library, the University of South Carolina with a nine-foot bronze likeness outside one of the campus libraries. None of the papers sheds light on Greener’s remove from his family with Genevieve.

Erasing History

Belle Greene burned her personal papers. She retired from the Morgan Library in 1948 but kept her hand in with regular visits. She was 71 when she died in 1950. Obituarists alluded to rumors about her family passing for white, but she seems never to have been identified publicly as Richard Greener’s daughter—or privately by her long-time employer, who had known Greener in the 1880s, when they served together on the Grant memorial commission. The only record of contact between Greener and his American family is correspondence from Vladivostok with daughter Louisa. The connection between the sophisticated, stylish doyenne of the Morgan Library and the roving intellectual and activist was obscured until 1999, when J.P. Morgan biographer Jean Strouse found Belle Greener’s 1879 birth certificate, which lists Richard Greener as her father. Father and daughter may have met once after he left the family; her biographer notes a passage in a letter alluding to a 1914 trip Greene made to Chicago “for important personal business” to meet in secret someone she had not seen in 20 years. Late in his life Greener enjoyed a loving correspondence with a daughter from his family in Siberia, who may never have known of her father’s heritage and travails.

Parallels between Richard and Belle are unmistakable: love of books, flamboyance, ebullience. The two also stand in contrast to one another. As Belle Da Costa Greene, Belle Greener never had to straddle boundaries of racial identity and community that entangled Richard Greener. She mostly eschewed politics, secure on her glittering perch—a position inconceivable for Belle Greener and her black father, who never concealed his ancestry. She had wealthy patrons; he stood alone, animosity all about him. Where Greene enjoyed extraordinary success and prosperity, Greener, unusually well-educated for his times and circumstance, frequently found himself excluded and often out of work. His activism on racial injustice threatened whites. His ease with whites aroused envy and suspicion among blacks. Sheltered by the Morgan fortune’s aegis of wealth and privilege, Greener’s daughter blossomed, achieving distinction for herself and the institution she directed. “But no one there could have been unaware of her taste, her intelligence, her dynamism,” a New York Times critic wrote in 1949. “For it was Miss Greene who transformed a rich man’s casually built collection into one that ranks with the greatest in the world.”

Her father would have been proud.

Decoding Duchamp

No other artist is as closely linked to conceptual art as Marcel Duchamp, who toyed with viewers’ expectations, creating works that puzzled and infuriated, including pieces he termed “readymades,” such as Fountain, a porcelain urinal he boldly submitted for display at a New York City exhibition in 1917. He also loved to fool with identity, famously creating his own alter ego, Rose Sélavy, as a play on the sounds of

Eros c’est la Vie (“The passion of love, that’s life”). Details encoded in Duchamp’s Belle Haleine go beyond changing the bottle from orange to green. The label shows Duchamp dressing fashionably, as Belle Greene might. The title—Belle Haleine—is a play on the French dessert, poire belle Hélène, a chocolate-dipped pear. Eau de Violette is close to “eau de voile” meaning “veilwater,” a possible reference to Greene’s adopted middle name, Da Costa. A more intricate reference appears in a 1921 letter from Duchamp to artist Francis Picabia that includes a pun about “bitterness shrinking the Negro.” Paleontologist and Duchamp decoder Stephen Jay Gould linked “shrinking” to Greene axing the “r” from Greener and the bitterness of blanching her blackness. All of this is conjectural. Another element to the puzzle is that Belle Haleine is also the first time Duchamp identified Rose Sélavy as “Rrose,” a hint that the added “r” might refer to the letter Belle Greener discarded to become Belle Greene. —Sarah Richardson