LIBRARY OF CONGRESS |

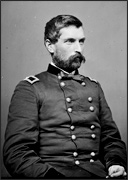

| General John Gibbon ended the war as a major general and a corps commander. |

As the bright red sun slowly set on a warm late summer evening, Union troops marching east along Warrenton Turnpike knew nothing of the danger that awaited them. The Federal soldiers had been scouring the Virginia countryside for days, looking for ‘Stonewall’ Jackson, who seemed to have vanished along with all his men. Yet all the Yankees would have had to do to find him was to look up the hill to their left, where Jackson was watching them from his horse.

Brigadier General Rufus King’s division was on patrol that evening. The division comprised three brigades of mostly green soldiers from New York and Pennsylvania and a fourth brigade manned by Westerners from Wisconsin and Indiana. The Westerners wore distinctive, tall Army-issue dress hats — hence their nom de guerre, the ‘Black Hat Brigade.’ An exceptional commander who had trained his brigade to the point of perfection led the Western soldiers. But Brigadier General John Gibbon, like his men, had yet to see battle in the Civil War.

The rookie Badgers and Hoosiers would soon face the flower of the Confederate Army, Maj. Gen. Thomas J. Jackson’s hard-marching veterans, in a stand-up infantry fight: the Battle of Brawner’s Farm. There, the Rebels would fail to decisively defeat a heavily outnumbered foe, and the men of King’s division would soon prove themselves every inch the soldiers that Jackson’s veterans were.

General Gibbon was a ramrod-straight, 35-year-old Philadelphian born in 1827. He had moved with his family to Charlotte, N.C., at a young age. While living in North Carolina, Gibbon was appointed to West Point, where he was schooled as an artillery officer and, due to academic problems, graduated a year behind schedule in the class of 1847.

After graduation, Brevet 2nd Lt. Gibbon served with the 3rd U.S. Artillery at Mexico City and Toluca during the waning days of the Mexican War but missed most of the fighting. Later he assisted in fighting the Seminoles in Florida, and by 1855 he was serving as an artillery instructor at his alma mater. Four years later, Captain Gibbon was sent to Utah as part of the Mormon Expedition, where he commanded Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery. After the firing on Fort Sumter in April 1861, Gibbon and his battery were ordered to Washington. While three of his brothers chose to fight for the South, Gibbon decided his loyalty to the Union meant more than family ties.

The Westerners spent much of late 1861 and early 1862 in the training camps that surrounded Washington and guarding railroads near Fredericksburg, Va. Gibbon became their brigade commander in June 1862, and by August the general and his men had come to respect, but not love, each other. He expected the same level of discipline and professionalism from his volunteers as he demanded of his Regular artillerymen. One soldier remarked, ‘Until we learned to know him, which we did not till he led us in battle, we seemed very far apart.’

Gibbon later explained the difficulties in training men who had recently been civilians: ‘The habit of obedience and subjection to the will of another, so difficult to instill into the minds of free and independent men, became marked characteristics of the command. A great deal of the prejudice against me as a Regular officer was removed when the men came to compare their own soldierly appearance and way of doing duty with other commands….’

During Gibbon’s tenure as the brigade’s commander, his Western boys won laurels as the foremost fighting brigade in the entire Union Army. In the words of Rufus Dawes, an officer in the 6th Wisconsin, ‘His administration of the command left a lasting impression for good upon the character and the military tone of the brigade, and his splendid personal bravery upon the field of battle was an inspiration to all.’

Changes that led to the Black Hat Brigade’s appearance on the field of battle began in late June 1862, when the Union created the Army of Virginia, commanded by Maj. Gen. John Pope. Gibbon’s brigade was assigned to that force and officially designated the 4th Brigade, 1st Division, of Maj. Gen. Irvin McDowell’s III Corps.

The new army had been formed after President Abraham Lincoln began to demand offensive operations in Virginia after months of inactivity by Maj. Gen. George B. McClellan’s Army of the Potomac outside the Confederate capital of Richmond. Pope’s mission was to march south and destroy the important railways in northern and central Virginia that connected the fertile Shenandoah Valley with Richmond.

Lincoln hoped to force General Robert E. Lee to shift some of his Army of Northern Virginia troops to northern Virginia to confront Pope, thus weakening Lee’s position outside Richmond and helping the Army of the Potomac. In mid-July, Lee did as Lincoln hoped, and sent two divisions under General Jackson, approximately 14,000 men, to the vicinity of Gordonsville, where the Virginia Central Railroad joined the Orange & Alexandria, to impede Pope’s southward march.

In late July, Maj. Gen. A.P. Hill’s division reinforced Jackson while Maj. Gen. James Longstreet and 29,000 men remained outside Richmond to guard against a possible attack by McClellan. After engaging and defeating a portion of Pope’s army at the Battle of Cedar Mountain, eight miles south of Culpeper Court House, on August 9, Jackson continued on to Manassas Junction, where he looted and destroyed Pope’s supply depot on August 27.

What would come to be called the Second Bull Run campaign had started quite well for the Confederates. Following the Battle of Cedar Mountain, Lee, aware that McClellan was moving his army northward, ordered Longstreet to move his men to Gordonsville.

By the morning of August 28, Jackson had deployed his 25,000 men along Stony Ridge, behind the embankments of a railroad grade of the unfinished Manassas Gap Railroad north of the little village of Groveton, near the old First Bull Run battlefield. From there, Jackson could monitor Union activity along the Warrenton Turnpike, a strategic east-west thoroughfare, while awaiting Longstreet’s arrival. Due to the concealment of Jackson’s defensive position, Pope had completely lost track of the Rebels’ movements after the destruction of Manassas Junction on August 27. Stonewall Jackson’s 25,000 soldiers were, in effect, missing as far as the Army of Virginia was concerned.

On the evening of August 28, Gibbon’s brigade of 1,800 Westerners sluggishly marched eastward toward the village of Centreville, where the majority of Pope’s army was massing. The 2nd Wisconsin (the only regiment in the brigade that had previously seen combat, at First Bull Run), the 6th and 7th Wisconsin and the 19th Indiana were getting very close to having a chance to show their mettle in battle.

It was approximately 5:45 p.m. when Gibbon’s brigade neared the open fields of John Brawner’s farm along Warrenton Turnpike, a mile west of Groveton. The soldiers were tired from a day of marching and countermarching, and their thoughts were of bedding down for the night, not of battle. As Gibbon looked to his north, he noticed horsemen near the Brawner farmhouse and wondered if they could be enemy cavalry. Moving off the pike to gain a better view, Gibbon saw Rebel artillery pieces unlimbering for action. Within a few minutes, at least two Rebel batteries fired on King’s division, which was still in marching columns that extended for nearly a mile along the turnpike.

Exploding shells quickly caused the skittish New Yorkers in Brig. Gen. Marsena Patrick’s brigade to scatter. Hours would pass before Patrick could re-form them. King suffered from epilepsy and, after suffering a seizure that afternoon, had turned over command to Brig. Gen. John P. Hatch. Hatch ordered Captain John A. Reynolds’ 1st New York Light Artillery to unlimber north of Groveton, and Gibbon soon had his old Battery B, 4th U.S. Artillery, which was attached to his brigade, move to a knoll a few hundred yards east of the Brawner farmhouse. The ground shook with the ‘wrath of the confronting batteries,’ one Union officer noted.

Gibbon then ordered his brigade to take cover on the north side of the road near the Brawner woods. He consulted with fellow brigadier Abner Doubleday, and both men were convinced that the Rebel guns belonged to Confederate horse artillery and that Jackson’s main force was miles away. Gibbon commanded the 2nd Wisconsin to silence the annoying guns and, if possible, ‘capture one of J.E.B. Stuart’s batteries.’ The Badgers marched off, formed into a battle line and threw out skirmishers as they neared the Brawner house. To their surprise, the Badgers saw a Confederate infantry brigade, also arrayed in battle line, moving toward them.

Eight hundred strong, those troops made up the famous ‘Stonewall Brigade.’ Once commanded by Jackson, the unit had gained everlasting glory at the First Battle of Bull Run and had served with Jackson during the Shenandoah Valley campaign. Now commanded by Colonel William S.H. Baylor, a lawyer from Staunton, the brigade of five veteran Virginia regiments outnumbered the Badgers by almost 2-to-1.

As each side waited for the other to come within rifle range, one Wisconsin soldier noted, the boys ‘held their pieces with a tighter grasp … expressing their impatience with low mutterings in such honest, if not classic phrases, as ‘Come on, God damn you.’ ‘ When the Virginians came within 100 yards of the Union line, Colonel Edgar O’Connor of the 2nd gave the command to fire, unleashing a volley into the Virginians. An officer in Baylor’s Brigade described the volley as ‘a most terrific and deadly fire.’ Minutes later, O’Connor, an 1854 West Point graduate, was mortally injured with wounds in the arm and groin, but his men continued to slug it out with the Virginians. He would later be laid to rest at Arlington National Cemetery.

After 20 minutes of fighting, Gibbon noticed the Rebel line starting to overlap the left flank of the 2nd Wisconsin, and he ordered the 19th Indiana to a position on the Badgers’ flank, a few yards east of the Brawner farmhouse. The Hoosiers, 423 men strong, moved into position but were met with a thunderous volley by the 4th Virginia. As the 19th steadied itself, Jackson desperately searched for more troops, encountering perhaps four regiments of Georgians under Brig. Gen. Alexander R. Lawton. They numbered between 800 and 1,000 men, and Jackson personally led them toward the fighting. Lawton’s regiments positioned themselves on Baylor’s left and joined the fight, overlapping the 2nd Wisconsin’s right flank. In response, Gibbon ordered the 440 men of the 7th Wisconsin to a slight rise on the right of the 2nd’s position. After some mingling and shifting of lines between the two regiments, the 7th Wisconsin finally anchored Gibbon’s right flank.

Meanwhile, Jackson desperately tried to ferry more troops into line against the brazen Yankees. After he deployed Lawton’s Georgia regiments, Jackson ordered Brig. Gen. Isaac R. Trimble’s Brigade to deploy on Lawton’s left in hopes of enveloping Gibbon’s line. At 60, Trimble was one of the oldest general officers in the Confederate Army. His 1,200 men from Alabama, North Carolina and Georgia had moved to within 75 yards of Gibbon’s line when they encountered a surprise on their left. At 6:50 p.m., while Trimble’s Brigade moved into position, Gibbon committed his last regiment to the fight, the 6th Wisconsin. The 500 men of the 6th Wisconsin, Gibbon’s largest regiment, moved toward low ground near a dry streambed that offered some protection from the Confederate artillery. When Trimble’s men were within 75 yards, Colonel Lysander Cutler gave the order to fire, and the 6th Wisconsin hammered Trimble’s stunned brigade. One Badger recalled, ‘Every gun cracked at once, and the line in front, which had faced us at the command ready’ melted away, and instead of the heavy line of battle that was there before our volley, they presented the appearance of a skirmish line.’ Trimble’s men soon took refuge behind the relative shelter of a wooden snake-rail fence that bordered the field, and each side continued its bloody work. As both sides blasted away at each other, Gibbon noticed a 250-yard gap between the right flank of the 7th Wisconsin and the left of the 6th Wisconsin. He sent word back to Hatch for reinforcements, but for reasons unknown, Hatch would send no help. After the battle, General Patrick attributed his brigade’s lack of involvement in the fight to not receiving formal orders to assist Gibbon. On his own initiative, General Doubleday sent the 450-man 76th New York and the 531 foot soldiers of the 56th Pennsylvania from his brigade into the expanding fight. The fresh troops moved into the large gap between the 7th and 6th Wisconsin and helped reinforce Gibbon’s quickly dwindling line.

Gibbon’s battle line was now complete and stretched for nearly a mile with a total of 2,781 men. In contrast, Jackson had three brigades in a line that stretched as far as Gibbon’s position and had a slight edge — 3,000 men — in the number of troops engaged. Jackson had more than 20,000 men at his disposal, but he had been unable to field even a quarter of that number.

Jackson requested reinforcements from both of his division commanders, but in the end Ewell managed to bring only two of his four brigades onto the battlefield, and the four-brigade division of Brig. Gen. William B. Taliaferro (pronounced ‘Tolliver’) only deployed one full brigade and half of another.

Jackson’s efforts were hampered by both of his division commanders being wounded during the action. As Ewell advanced with the 12th Georgia on the extreme Rebel left, he knelt down to gain a better view of the Union line, and a Mini ball shattered his left kneecap. The crippled Virginian was taken to the rear, where his leg was later amputated. Ewell’s Division would be leaderless for the rest of the fight.

On the other flank, Taliaferro, commander of Jackson’s old division, advanced toward the Brawner farmhouse, only to be wounded three times by Yankee rifle fire. Taliaferro refused to leave the field until the fighting was over. Due to his feeble condition, however, he was unable to deliver the authoritative leadership his division needed.

The Southern problems were compounded when Union lead began felling regimental commanders. Colonel Lawson Botts of the 2nd Virginia, a former lawyer who had defended John Brown in the famous 1859 trial, suffered a mortal head wound while encouraging his men near the left of the Stonewall Brigade line.

Colonel John Francis Neff of the 33rd Virginia had been suffering from heat exhaustion all week and was ordered to the rear by a surgeon prior to the battle. He refused any medical aid, opting to stay and fight with his men. As Colonel Neff walked down his line, exhorting his Virginians, he was killed instantly when a bullet entered his left cheek and exited his right ear.

Frustrated with the battle’s progress, Jackson decided to go on the offensive. At approximately 7:15 p.m., he ordered his entire line to advance upon the recalcitrant Union defenders. The first to respond to Jackson’s order was Trimble’s Brigade. Due to the miscommunication that would plague the Confederates throughout this engagement, however, only two of Trimble’s regiments responded to Jackson’s call.

The 21st Georgia and 21st North Carolina — called ‘my two twenty-firsts’ by Trimble — started toward the 56th Pennsylvania and the 6th Wisconsin at about 7:30 p.m. For reasons unknown, Trimble’s two left regiments, the 15th Alabama and the 12th Georgia, failed to advance. The Pennsylvanians poured a devastating volley into the ‘two twenty-firsts’ as they advanced without flank support, while the 6th Wisconsin delivered an oblique fire into the Rebels’ left flank. The Rebel lines seemed to melt before the storm of Yankee lead.

One officer in the 6th Wisconsin remembered, ‘The men [Southerners] loaded and fired with the energy of a madman and a recklessness of death truly wonderful, but human nature could not stand such a terrible wasting fire … it literally mowed out great gaps in the line.’

The whirlpool of death claimed Lt. Col. Saunders Fulton of the 21st North Carolina as he led his men forward with bayonets fixed. Dozens of his men were swept away. The Georgians suffered a similar fate. As one remembered, ‘The blazes from their guns seemed to pass through our ranks.’ The 21st would lose 184 of 242 men in the battle, 76 percent of its strength. One Georgia company pitched into the Yankees with 45 men, but only five emerged from the fray unhurt. Trimble’s advance had been halted, but Jackson’s offensive was far from over.

Jackson personally ordered Lawton’s Georgia brigade to move forward at 7:45 p.m., but once more only two regiments responded. Jackson led the Georgians toward their parlous undertaking. In the fading sunlight, the 26th and 28th Georgia advanced obliquely toward the 2nd Wisconsin. Their attack was short-lived. As they advanced, the 7th Wisconsin and the 76th New York wheeled to the left and poured a lethal volley into the Rebels’ flank. Colonel William W. Robinson of the 7th Wisconsin wrote, ‘The evolution was executed with as much precision as they ever executed the movement on drill. This brought us within 30 yards of the enemy.’

One man in the 7th reported, ‘Our fire perfectly annihilated the rebels.’ While the Southerners received fire from their flank, the 2nd Wisconsin poured deadly volleys into the Georgians’ front. ‘No rebel of that column who escaped death will ever forget that volley. It seemed like one gun,’ said one New Yorker.

The 26th Georgia suffered 74 percent casualties in its feckless assault (134 of 181 men). One Wisconsin officer noted: ‘Our boys mowed down their ranks like grass; but they closed up and came steadily on. Our fire was so terrible and certain that after having the colors in front of us shot down twice they broke in confusion and left us in possession of the field. They left their colors upon the field.’ Jackson’s short, violent offensive had ended, but the two sides continued to bloody each other in a classic, stand-up infantry fight.

As the late summer sun set behind the Bull Run Mountains, the blue and gray battle lines continued to blast away at each other at point-blank range, neither side budging an inch, separated by less than 30 yards in some places. The men could barely make out the dark silhouettes of the opposing battle lines and instead fired at their opponents’ bright muzzle flashes. ‘The two crowds, they could hardly be called lines, were within, it seemed to me, fifty yards of each other, and were pouring musketry into each other as rapidly as men could load and shoot,’ remembered one Union veteran. Men were dropping with every volley — almost two dozen men every minute — but neither side yielded any ground. A veteran of some of the heaviest fighting of the entire Civil War, Gibbon later recalled, ‘The most terrific musketry fire I have ever listened to rolled along those two lines of battle … neither side yielding a foot.’

On the Union left, Colonel Solomon Meredith, the 6-foot-7-inch commander of the 19th Indiana, galloped up and down his line, extolling his men. Known as ‘Long Sol’ to his troops, Meredith was nearing the farmhouse when he noticed a large body of Rebel infantry bearing down on his left flank. The 600 fresh troops were from Colonel Alexander G. Taliaferro’s mixed brigade of Virginians and Alabamians, and they represented the last of Jackson’s immediate reinforcements on that part of the field.

Colonel Taliaferro advanced the 10th, 23rd and 37th Virginia regiments from his brigade against the 19th, hoping to enfilade Gibbon’s left flank. The colonel’s other two regiments, the 47th and 48th Alabama, were still en route to that part of the field and would not reach their brigade until after the fight. During this action, Taliaferro, an uncle of division commander W.B. Taliaferro, was seriously wounded and never again held field command.

As Taliaferro’s Brigade advanced, Captain John Pelham of Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart’s Horse Artillery moved two of his cannons to a knoll only 100 yards from the Hoosiers’ line and began pouring deadly salvos of canister into Meredith’s men. Meredith was severely injured when his horse was shot and fell on top of him during this action. His men, however, put up a strong fight until General Gibbon ordered them to fall back to a new position. But the combination of fresh Rebel troops, Pelham’s guns and nearly complete darkness forced the Indianans to abandon their position entirely.

Sometime after 8 p.m. and the onset of darkness, the fighting died down. The crackle of musketry eventually faded into the groans of the wounded, as each side sought to collect its dead and wounded and burial parties from both sides searched for friends and loved ones.

Lacking sufficient numbers to maintain a defense and not wishing to provoke Jackson any further, at 11 p.m. the ailing Rufus King resumed command and decided to withdraw his battered division to Manassas Junction, eight miles to the south, where much of Pope’s scattered army was gathering.

On the following two days, August 29 and 30, Lee and Pope would fight it out in the Second Battle of Bull Run. The first day of the fight, Jackson held off Union attacks on his position. On the 30th, King’s division, again commanded by Hatch, helped attack Jackson’s position in the afternoon. Whatever hopes Pope had for success were dashed when Longstreet came up on the Confederate right and delivered a punishing blow that broke the Federals. That evening, Gibbon’s brigade skillfully acted as the rear guard for Pope’s withdrawal from the battlefield. The Second Bull Run campaign, a dismal failure for the North, ended when Pope’s soldiers marched into Washington after the Battle of Chantilly on September 1.

The Black Hat Brigade, however, suffered the most at the Battle of Brawner’s Farm. Gibbon’s brigade lost almost 800 killed or wounded, including nearly 200 men killed outright and dozens more who would die of their wounds, in that two-hour fight. The 2nd Wisconsin, Gibbon’s first unit to be engaged, suffered the most casualties: 297 men killed or wounded out of 430, including 83 men killed outright.

On the Union left, the 19th Indiana suffered nearly 260 casualties of 423 men engaged — more than 60 percent of its strength. Farther down the line, the 7th Wisconsin suffered 220 casualties out of 440 men. Doubleday’s two regiments each lost about 100 men killed and wounded. Finally, on the far Union right, the 6th Wisconsin sustained the fewest casualties due to the protective terrain of that part of the field — 72 men killed and wounded.

The brigade’s leadership also suffered. Of the four regimental commanders, one was killed and the other three were wounded. All told, the Federals lost nearly 1,100 men out of about 2,800 engaged — almost 40 percent casualties in two hours of fighting.

Jackson’s men also lost heavily. The Stonewall Brigade had two regimental commanders killed and suffered roughly 300 casualties — a little less than 40 percent of its strength. Lawton’s Brigade incurred more than 300 casualties, with the 26th Georgia losing 74 percent of its men. Trimble’s Brigade, which was only engaged for one hour, lost nearly 350 men killed or wounded, almost one-third of its strength.

The 21st Georgia lost 76 percent of its men. According to official Confederate records, only the 1st Texas at Antietam would have a higher casualty percentage during the entire war, 82.3 percent. Colonel A.G. Taliaferro’s Brigade would lose 87 men, a relatively low number, in its short fight with Meredith’s Indianans. Of the approximately 3,500 Rebels participating that evening, 1,100 became casualties, over one-third of the Confederate troops engaged, nearly identical to their adversary’s grim toll.

At Brawner’s Farm, Jackson fielded only two understrength, yet complete, brigades — Baylor’s and Trimble’s — and a few regiments of two other brigades commanded by Lawton and A.G. Taliaferro. The combined strength of the four brigades barely outnumbered the six Union regiments opposing them.

There are a number of reasons for Jackson’s poor performance at Brawner’s Farm. Known for his brilliant use of maneuver to gain tactical advantage during the Shenandoah Valley campaign, Stonewall contented himself with uncoordinated and unsuccessful frontal assaults and failed to communicate well with his division commanders. Thus brigade commanders being in the dark led to uncoordinated, piecemeal regimental assaults. In Jackson’s defense, when Ewell and W.B. Taliaferro were wounded, he was forced to lead individual regiments into battle, something a major general should not have to do. Jackson, however, also failed to bring sufficient artillery into action against the Union troops. His miserly use of artillery allowed the Union troops to bring up reinforcements.

Lastly, Jackson had difficulty achieving his objectives because his men were up against possibly the best brigade in the Union Army. Gibbon, in his first major battle as an infantry commander, used his regiments brilliantly, deftly plugging them into key positions as different threats arose. Due to Gibbon’s relentless training of his men, and the Westerners’ determination to prove themselves as fighters, the soldiers stood their ground and did not yield a foot until ordered. The Black Hat Brigade’s magnificent performance would be repeated again on many a bloody field — but the men in Gibbon’s brigade would never forget their baptism of fire at Brawner’s Farm.

This article was written by Todd S. Berkoff and originally appeared in the September 2004 issue of America’s Civil War. For more great articles be sure to pick up your copy of America’s Civil War.