In late ad 74 Emperor Ming of China’s Han dynasty assigned Geng Gong, a midlevel field officer, to command the 500-man garrison at Jinpu, a strategically important fortress on the northern slopes of the Tian Shan Mountains near the east end of the Silk Road. The emperor entrusted the garrison with three key missions: first, to patrol for bandits and protect the rich caravans that plied the famed trade route; second, to keep an eye on the subjugated Jushi kingdom, which had only recently been conquered by the Han; third, and perhaps most important, to prevent the advance of an ancient enemy—the nomadic Xiongnu.

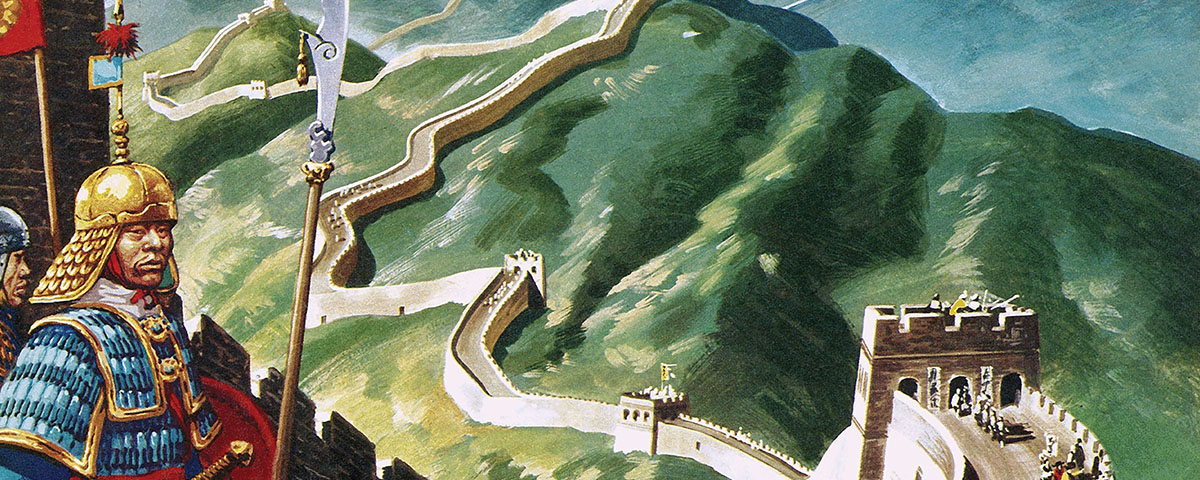

In 221 bc King Zheng of the state of Qin completed his conquest of a half-dozen surrounding states and proclaimed the Qin empire (221–206 bc), naming himself first emperor of a unified China. Toward the end of Zheng’s reign, around 215 bc, the Xiongnu began encroaching on Qin lands, prompting Zheng to send General Meng Tian and an army of some 100,000 men to drive the nomads north of the Yellow River. That done, Zheng then ordered construction of the Great Wall to keep the barbarians out of his empire. The directive came just in time, as the emperor himself died in 210 bc, and the next year a nomadic chieftain named Modun set out to conquer several large northern tribes and establish the Xiongnu empire, which soon spanned Central Asia.

Over the next century the Xiongnu sought to expand into the region held by the Chinese—first under the Qin emperors and later the Han (206 bc–ad 220). During the latter dynasty the Xiongnu repeatedly threatened Han territory and almost captured Liu Bang, the first Han emperor, at the 200 bc Battle of Baideng. After that near debacle the Han emperor initiated a policy of rapprochement with the Xiongnu. Liu Bang and his successors sought to placate the nomads by sending them vast amounts of treasure, as well as providing imperial Han princesses as brides for Xiongnu chieftains. While the concessions forestalled full-scale war between the empires, Xiongnu riders continued to stage border raids into China, and the imperial Han army continued to mount punitive expeditions against the Xiongnu. Such expeditions almost always ended in Han victories, for the dynasty’s army was superior in discipline, weaponry and leadership. The centuries of nearly continuous combat during the Warring States period (475–221 bc) had shaped the imperial Chinese army into a disciplined force that fought effectively as a cohesive unit.

The nomads did boast one tactical advantage over the Chinese—superior horsemanship. The Han military commanders acknowledged that superiority and resolved that the best way to counter the Xiongnu horsemen was with an equally robust cavalry force. Toward that end imperial administrators encouraged the general populace to raise horses, exempting those who did so from taxes and labor levies. During the reign of Emperor Wu (141–87 bc) the imperial army launched full-scale attacks against the Xiongnu. In addition to cavalry, the Han employed large numbers of crossbowmen, whose weapons far outranged the nomads’ traditional recurve bows.

During the subsequent century of protracted warfare between the realms, the Han conquered and assimilated many southern Xiongnu tribes. Some of the nomads wound up in the Chinese army, fighting against their northern Xiongnu cousins—not unlike Roman recruitment of barbarians into the legions. Eventually, most of the remaining belligerent Xiongnu tribes withdrew to the north or west, counting among their descendants Attila and his Hun hordes.

While the Great Wall largely barred the Xiongnu from venturing south against the Han empire, Geng Gong was further tasked with severing communications between the nomads and western kingdoms (thus deterring any alliance that might threaten the imperial realm) and with thwarting attacks from the west against the empire. In December 74 Emperor Ming summoned home the Han expedition that had conquered Jushi, stationing Geng Gong at Jinpu and another garrison commander at Liuzhong, on the southern slopes of the Tian Shan, to guard the frontiers. The following spring some 20,000 Xiongnu riders poured south, seeking to wrest control of Jushi.

Geng Gong sent a deputy with 300 men to bolster the Jushi people, but the Xiongnu ambushed the relief column en route and wiped it out. The loss of 60 percent of his command was undoubtedly of great concern to Geng Gong, as he knew an attack on his own garrison was only a matter of time. In preparation for the inevitable assault, he reinforced the bulwarks at Jinpu and ordered his men to dip the heads of their arrows and crossbow bolts in poison. A nasty fight was in the offing.

After making short work of the Jushi kingdom, the Xiongnu army advanced on Jinpu. As the enemy troops gathered for the attack, Geng Gong mounted the battlements and shouted down a warning to the nomads: “Any man hit by Han bolts and arrows shall suffer painfully, because the missiles were sent by the gods to the Han emperor.” It was not an idle threat, for when the Xiongnu troops launched their opening assault, those hit by the poison-tipped Han projectiles suffered caustic, festering wounds. The agonized warriors’ cries and mournful moans further demoralized their uninjured comrades, who withdrew in disarray. Then, under the cloak of darkness and a thunderstorm, Han soldiers raided the Xiongnu encampment. The violent surprise attack by troops wielding broadswords and halberds broke the siege and drove the Xiongnu away from the fortress.

But the nomads weren’t beaten yet.

In the aftermath of his victory against the Xiongnu, Geng Gong recognized the weakness of his own position and moved his command south to the Shule fortress, sited on more defensible ground along a stream that provided a reliable water supply for his men and animals. The Han commander also stocked up on food, weapons and other supplies and recruited several thousand Jushi auxiliaries to bolster his force. The move negated the nomads’ advantages in numbers, speed and mobility, again forcing them to attack fixed defenses.

When the Xiongnu reappeared that July, Geng Gong was ready. Indeed, before the nomads could form for battle, the Han commander struck, sending out his professional troops and auxiliaries to engage the enemy. The Xiongnu had expected to face numerically insignificant Han defenders, and the startlingly large force fielded by Geng Gong panicked the nomads into another retreat.

Within weeks the Xiongnu resumed their offensive. After repeated attacks failed to breach the fortress walls, they settled into a siege. Their first act was to dam the stream that provided water to the Han garrison. In the blazing summer heat the defenders quickly began suffering from dehydration. When newly dug wells sunk 150 feet failed to strike water, the desperate Han drank their horses’ sweat and urine to quench their thirst. Fortunately, a renewed well-digging effort personally led by Geng Gong was successful. On his direction the elated Han soldiers hauled jugs of water atop the battlements and symbolically poured the precious liquid over the attackers massed at the base of the walls. The demonstration demoralized the nomads, who must have been convinced the gods were indeed watching over the Han troops.

Unfortunately for Geng Gong and his men, Emperor Ming died that September and left no one to authorize a relief force. To make matters worse, in the interim the king of Jushi had capitulated to the Xiongnu and sent his army to join the nomads in the siege of Shule. Geng Gong’s Jushi auxiliaries soon melted away. Fortunately for the Han defenders, the Jushi queen was of Han ancestry. She smuggled food and supplies to the garrison and provided intelligence on the Xiongnu and Jushi attackers. Despite the queen’s assistance, Geng Gong and his men soon neared starvation. They resorted to boiling the leather and sinews from their clothing, armor, shields, helmets and bows to slake their hunger.

Realizing the Han defenders were short of supplies, the Xiongnu chieftain sent an envoy to the fortress with generous terms for Geng Gong: “If you surrender, we will name you as King Bai Wu and give you women for wives.”

Geng Gong glared down at the Xiongnu envoy, then back at the starving troops arrayed around him. The men looked to their commander to decide the garrison’s fate. Geng Gong agreed to negotiate the garrison’s surrender. Han soldiers lowered a rope and hauled up the enemy envoy. Then, to everyone’s shock, Geng Gong drew his sword and abruptly killed the man. He then ordered the body to be butchered and boiled in a large pot placed conspicuously on the fort’s rampart. While his soldiers feasted on the envoy’s flesh, Geng Gong hollered down to horrified enemy onlookers, “This is what happens to any Xiongnu that reaches my battlements!” While the killing and consumption of an envoy under a flag of truce was certainly ghastly and unprecedented, it did serve to alleviate the garrison’s hunger and demonstrate the defenders’ resolve to continue the fight. At the same time, Geng Gong had preempted any possibility of surrender. Cannibalism of one’s enemy was a clear declaration of “no quarter.”

The onset of cool weather presented a new problem for Geng Gong, as he and his men had eaten much of their leather clothing and gear. If the garrison was to survive the winter, they needed new equipment. Geng Gong sent a subordinate named Fan Qiang through enemy lines to requisition supplies from the Han base at Dunhuang. But its garrison commander refused, explaining to Fan Qiang that any resupply or reinforcement required the new emperor’s authorization. Help was not coming.

By the spring of 76 the besieged Han defenders at Shule were in dire straits. Though they had held off a 20,000-man Xiongnu army for a year, only Geng Gong and two-dozen of his original 500 men remained alive. Worse still, their most effective weapon—the crossbow—was useless, as archers had already dropped their bowstrings into the stewpot. Then came the fateful day when sentries reported vast numbers of mounted men approaching the fortress. Despair gripped the Han survivors as they struggled to the parapet, expecting yet another nomad attack. Instead, a familiar voice hailed them: “I am Fan Qiang! The emperor has sent an army to bring you home!” Pandemonium broke out within the fort. With tears streaming down their faces, Geng Gong’s men threw open the gate and welcomed their saviors.

The next day Geng Gong and the other Han holdouts joined the 2,000-man relief force for the 200-mile trek home. En route they struggled through massive snowdrifts in the Tian Shan Mountains and were harried by pursuing nomads. By the time they reached Yumen Pass, only 13 of Geng Gong’s men, counting Fan Qiang, remained alive to stagger through the western gates of the Great Wall.

Geng Gong’s successful yearlong defense against a vastly superior enemy force, despite shortages of food and water, spoke well for the commander and his unit. More than a millennium later the feat inspired General Yue Fei to write a poem—featured at the beginning of this story—to motivate his men to fight northern Jin invaders, descendants of the nomadic Xiongnu raiders.

Despite his achievements, however, Geng Gong never rose to the general rank. The reason? While he had successfully defended the realm against barbarian invaders, he had failed to expand its borders to the glory of the Han emperor.

Tang Long (aka William Tang) is a consultant on China. He wrote the “Tales of the Dragon” column for the WashingtonTimes.com and authored The Book of War, the first chronological account of ancient Chinese military history written in English. For further reading he recommends the Book of Han, by Ban Gu and Ban Zhao; Records of the Grand Historian, by Sima Qian; Romance of the Three Kingdoms, by Luo Guanzhong; and his own The Book of War.