Blunders by U.S. generals and courageous stands handed the country two iconic victories

Between July 1812 and 1813, the United States, at war with Great Britain, tried and failed seven times to invade Canada. In autumn 1813, an eighth attempt sent two American armies to seize the St. Lawrence River and Lower Canada, now Quebec Province. A textbook study in how not to coordinate an offensive strategically and tactically, the St. Lawrence campaign brought about one of the bloodiest land battles of the War of 1812 and a pair of battlefield encounters Canadians regard as iconic.

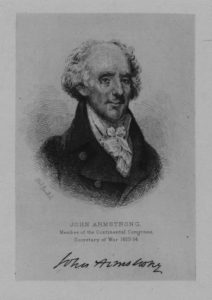

U.S. Secretary of War John Armstrong Jr., who held the Army rank of lieutenant general, conceived the St. Lawrence campaign as a two-pronged invasion that he originally intended to lead himself. He soon delegated command of the larger force, however, to his second in command, Maj. Gen. James Wilkinson. Wilkinson was to lead 8,000 troops accompanied by a squadron of gunboats and bateaux out of Sacketts Harbor, New York, on the southeastern corner of Lake Ontario, and move north along the St. Lawrence River, where it would meet 4,000 men under Maj. Gen. Wade Hampton, coming up from Plattsburgh, New York, about 170 miles east-northeast. As a prelude to conquering all of Lower Canada, a region of 206,250 square miles, the combined divisions were to capture Kingston on Lake Ontario. Soon, however, Armstrong, judging that lake port too well defended, changed the objective to Montreal. He expected the expedition to commence on September 15, 1813.

Armstrong’s scheme went awry from the beginning. In September both he and Wilkinson were reported to have come down with unspecified maladies. Armstrong elected not to lead the campaign himself. He left it to Revolutionary War veterans Wilkinson—whenever he sufficiently recovered—and Hampton to jointly carry out the plan.

The pairing was inherently ill-starred. The Maryland-born Wilkinson had been general in command of the U.S. Army since 1800. At 66, he was senior in age and tenure to Hampton, 61. Hampton, who despised Wilkinson, had not been on speaking terms with him since 1808. To mute the South Carolinian’s ire, Armstrong assured Hampton that orders to him would come through the War Department rather than directly along the chain of command from Wilkinson.

Hampton was not alone in loathing his designated superior. Wilkinson had long been notorious for shady dealings and remarkable fortune; as often as he was court martialed, he eluded conviction. Now came another war offering chances at redemption. In summer 1813 Wilkinson had occupied Mobile in Spanish West Florida, a minor feather in his cap. Orders that July to assume command at Sacketts Harbor and ready an expeditionary force against the British brightened his prospects.

On Independence Day Hampton arrived at Burlington, Vermont, where his troops were staging, to learn that most of his new command, which included a 1,400-man brigade of New York militia, was poorly trained. His junior officers were green. His quartermasters had barely enough supplies to sustain a prolonged march, let alone any siege he might have to undertake. On September 19 he transported his force across Lake Champlain to his forward base at Plattsburg, only to find the supplies stockpiled there inadequate. Hampton led a reconnaissance in force north to Odelltown, Quebec, but abandoned that route in order to avoid a British base at Ile de Noix that harbored 900 soldiers and enough gunboats to dominate Lake Champlain. Instead, Hampton marched west to Four Corners—now Chateaugay, New York—on the Châteauguay River and settled in to await word of Wilkinson’s next move.

On October 18 Hampton finally received a communiqué from the still-ailing Armstrong. The secretary of war, who had departed Sacketts Harbor for Washington on October 16, reported Wilkinson’s force to be about to get under way. Hampton duly resumed his march. At the Canadian border his 1,400 New York militiamen refused to cross, citing opposition to fighting their neighbors. Hampton entered Lower Canada with 2,600 U.S. Army infantrymen, 200 cavalry, and 10 field guns.

At that point the British, alerted to the Americans’ advance, were taking steps to deal with the incursion. After 15 months of hostilities, theCrown still viewed the “American War” as an irritating distraction from the empire’s real fight against Napoleon in Spain. British regular army forces in North America now exceeded 13,000, but in units so widely scattered that to supplement their meager numbers the army depended on five “fencible” regiments—Canadian conscripts with British commanders—as well as local, or “sedentary,” militia and allied Indian tribes. Militia forces, which dressed less expensively than regulars, were known for their gray-dyed uniforms and coats.

Realizing the Americans meant to attack his city, on September 17 Maj. Gen. Louis de Watteville, Swiss-born commander of the Montreal District, ordered the militia raised. At the same time Lt. Gen. George Prevost, governor general of North America, ordered a composite battalion of British regulars and Canadian militiamen led by Lt. Col. George MacDonnell to march some 180 miles from Kingston to a blocking position south of Montreal.

Hampton’s most direct route through the Canadian wilderness to Montreal was along the banks of the Châteauguay. Near that river’s junction with a creek called the English River stood his first obstacle—a mixed force of local Canadian units whose nucleus, the Voltigeurs de Québec, was a light infantry regiment of French Canadians. Loyal to the Crown, the Voltigeurs nonetheless spurned red coats, preferring gray uniforms with black bearskin hats. Their Quebec-born commander, Lt. Col. Charles-Michel d’Irumberry de Salaberry, had served in the Napoleonic Wars and brought the resulting hardnosed professionalism to drilling his men. During an earlier American incursion, Salaberry had led about 100 Voltigeurs and 230 Kahnawake Mohawk Indians in repulsing 650 U.S. Army invaders at Lacolle Mill, near Quebec, on November 19, 1812.

MacDonnell arrived from Kingston with orders to supplement the Voltigeurs and militia. Salaberry installed breastworks and abatis—tangles of tree branches—on either shore of the Châteauguay, blocking the road at a ravine near the English River mouth, where woods gave way to a small patch of cleared ground. There Salaberry waited with his first line of defense: 150 Voltigeurs, 50 fencibles, 100 sedentary militia, and two dozen Indians. Behind these fighters MacDonnell staged a series of reserve lines comprising 300 Voltigeurs, 580 militiamen, and 150 Indians. These lines guarded access to the river, including Grant’s Ford, which offered the enemy an opportunity to cross the Châteauguay and cut Salaberry’s vanguard off from his reserve forces.

Local farmers monitoring the Americans’ advance kept Salaberry and his officers well informed of the enemy’s movements; the Americans proceeded in ignorance. Hampton’s advance scouts had located Grant’s Ford, however, and on the evening of October 25 Hampton dispatched Colonel Robert Purdy with 1,000 troops on a 16-mile march to cross the Châteauguay at the ford. At dawn Purdy was to flank the enemy from the south. But Purdy’s guides did not know the terrain, and his cohort got lost in a hemlock swamp, spending a miserable night under pouring rain.

In the morning, Hampton received a belated dispatch from Armstrong to the effect that he was departing Sacketts Harbor—he had, in fact, done so 10 days before—and left command to Wilkinson. Hampton was to prepare winter quarters for 10,000 troops along the St. Lawrence. Inferring from the order that Armstrong was writing off the campaign, a disgusted Hampton wrote a letter resigning his command. Had he not felt concern about Purdy and his lost brigade, Hampton would have withdrawn his force forthwith. Instead, he committed a brigade under Brig. Gen. George Izard to a frontal assault on Salaberry’s first line of breastworks.

At dawn October 26, Purdy regained his sense of direction only to get lost again at mid-morning and have most of his brigade emerge from woods not at Grant’s Ford, but just south of Salaberry’s first line of defense. Some Canadian militia attacked the Americans, who drove them back, wounding two ranking militia officers. Hotly engaged by additional militia and Indians, some of Purdy’s troops retreated—into friendly fire from the nervous troops behind them.

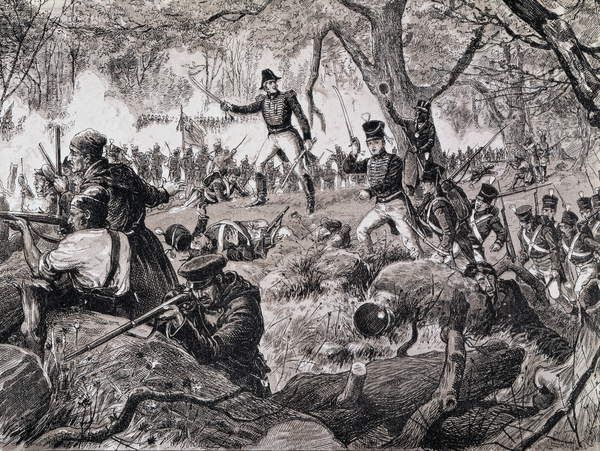

Around midday Izard’s 1,000 U.S. Army troops reached the ravine facing Salaberry along the north shore of the Châteauguay. At 2 p.m. Hampton ordered them into action. The Americans lined up to engage 300 dug-in defenders with rolling volleys more suited to a European battlefield than the uneven terrain at hand. An American officer is said to have ridden up and in French ordered Salaberry to surrender. The American was not carrying a white flag, however, so Salaberry shot him. In 45 minutes of fighting, elements of Izard’s force drove back the fencibles on Salaberry’s right flank until reinforcements arrived to restore that line.

Throughout the fighting Salaberry was said to have stood atop a stump, subsequently writing his father that he had led from a “wooden horse.” Hoping to fool the Americans as to his force’s actual size, he encouraged his flankers, concealed among trees, to produce a cacophony of bugle calls, cheers, and war whoops—with considerable success. Finally, a British bugle signal to advance reportedly convinced Izard he was outmatched. His force retreated three miles.

About that time Purdy reached a location at which he hoped to connect with Izard’s advancing force and get his wounded ferried to the American shore. Instead, Purdy came under fire from Salaberry’s advance element. The Americans fell back and spent another wretched night of meandering before reconnecting with Hampton.

A post-hoc conference by the invaders counted 23 Americans killed, 33 wounded, and 29 missing. Salaberry had taken 16 American prisoners, against the loss of two of his men dead, 16 wounded, and four missing. Disengaging at about 4 p.m., Hampton withdrew to Four Corners, sending a subordinate to update Armstrong in Washington.

Prevost and de Watteville, who arrived just after the fight, submitted after-action reports in which they took the credit for a fabulist victory by 300 militiamen over 7,500 Americans. Salaberry, furious at his superiors’ misrepresentations, considered resigning, but truth prevailed. In the end Salaberry got recognition and thanks from the Quebec legislature. He and MacDonnell later received chivalric honors as Knights Companions of the Bath.

Châteauguay was as remarkable a victory for the militia of Lower Canada as it was a profound embarrassment to the U.S. Army. Nevertheless, the threat to Lower Canada was far from over. At Sacketts Harbor on October 17, the main prong of the invasion—Wilkinson and his 8,000-man division—finally got under way.

Wilkinson originally planned to seize Kingston and then join Hampton, but his Navy flotilla commander, Commodore Isaac Chauncey vetoed the idea due to the powerful British naval presence there. Crossing the St. Lawrence on November 4 at French Creek, near present-day Clayton, New York, the Americans came under bombardment by British brigs and gunboats until their artillery drove off the waterborne attackers. Wilkinson was marching his troops northwest when he learned on November 6 of Hampton’s defeat at the Châteauguay. Wilkinson sent Hampton orders to march west from Four Corners to Cornwall, 114 miles up the St. Lawrence from Kingston, and join his force. Wilkinson then resumed his advance on November 7, bypassing a British post at Prescott, across the river from Ogdensburg, NY.

At a November 9 council of war senior commanders, undiscouraged by Hampton’s defeat and the news that a large British force was trailing them, persuaded Wilkinson to push on.

At Kingston, Maj. Gen. Francis de Rottenburg, lieutenant governor of Upper Canada, had learned of Wilkinson’s movements. He dispatched a 650-man “Corps of Observation” to follow and harass the Americans. Its leader, Lt. Col. Joseph Wanton Morrison, had been born in New York in 1783 shortly before the British evacuated that city, and had fought in the Netherlands before returning to North America as commander of the 2nd Battalion, 89th Regiment of Foot. En route, his task force swelled, incorporating fencible and militia units, Voltigeurs, and 30 Tyendinaga and Mississauga Mohawks, its ranks eventually nearing 900.

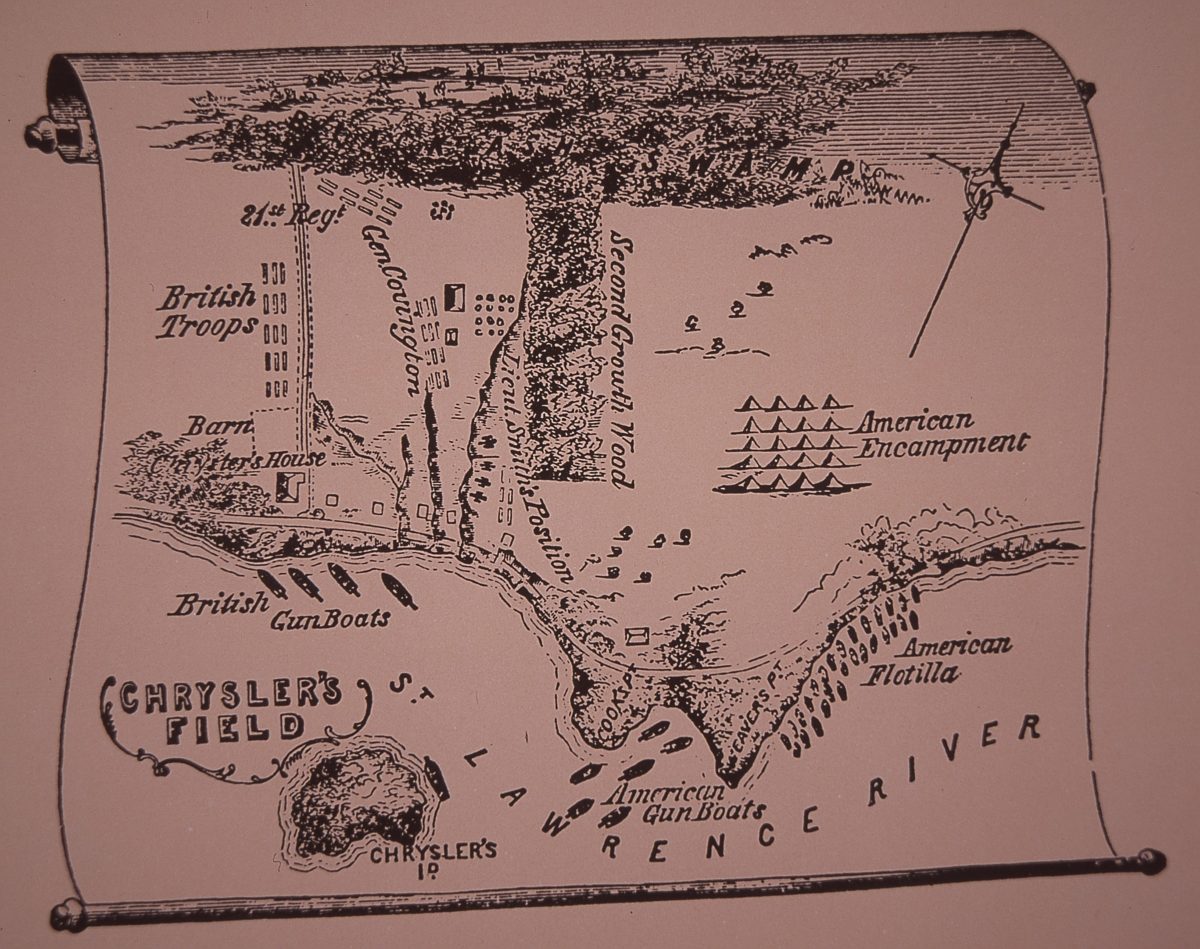

At Hoople Creek, west of present-day Cornwall, Ontario, on the evening of November 10, Wilkinson’s vanguard encountered and drove off 500 local Canadian militiamen. Behind Wilkinson, the Corps of Observation bedded down at a farm owned by one John Crysler, near the town of Morrisburg. The American rear guard was two miles upstream.

November 11 was dawning raw and rainy when shallow-draft British gunboats fired on Americans encamped around Cook’s Tavern, where Wilkinson had set up his headquarters. Inland, a Mohawk shot at American scouts. The Americans returned fire, sending half a dozen Canadians rushing to alert Morrison’s force of an American attack. Dropping half-eaten breakfasts, the redcoats stood to arms. So did the Americans at Crysler’s farm.

At 10:30, Wilkinson learned that since the previous day’s battle at Hoople Creek an overland route to the rapids had opened. Before taking advantage of that access, however, he wanted to eliminate the enemy force hectoring his rear guard. He ordered Brigadier General John Parker Boyd to take 2,500 infantry and dragoons and deal with the annoyance.

On the British side, Colonel Morrison was on the kind of open ground he liked—muddy, yes, but ideal for the musketry at which his redcoats excelled. While his 500 regulars lined up in the center, supported by two six-pound cannon, Morrison anchored his right flank against the St. Lawrence River with light and grenadier companies, fencibles, and a third six-pounder, a gulley separating that part of the line from the foe. In the woods to the British left, Voltigeurs, militiamen, and two dozen Indians took up skirmishing positions.

The Americans sought to turn the British left flank, starting with an infantry thrust that drove the Canadians a mile back through the forest. Pausing for breath, those American infantrymen, joined by others, emerged from the woods to the redcoats’ left. In response, the well-drilled British wheeled and with a withering series of volleys drove the attackers to cover in disorder.

A separate American force, led by Brig. Gen. Leonard Covington, struggled across the gulley, reaching the open field to behold a line of men at arms in gray. At the sight of their dress, Covington is said to have shouted, “Come on, lads, let’s see how you will deal with these militiamen!” Under those gray raincoats, however, were the red coats with green facings of Morrison’s 89th Foot. The British regulars fired, mortally wounding Covington; shortly after, when his second in command died, the entire brigade lost cohesion.

At the riverside, six American cannon crews belatedly unlimbered and began an effective bombardment. To silence the guns, redcoats attacked, struggling over fences and enduring heavy casualties but nevertheless closing on the enemy battery. Trying to save the field pieces, American dragoons came on once and again, only to be caught in a crosshatch of musket and cannon fire. Of 130 dragoons, 18 were killed or wounded, a sacrifice that allowed the American artillerymen to recover five guns. The sixth charge bogged down and was captured by redcoats. By 4:30 nearly all the Americans were in full retreat. At dusk the British ceased pursuit and the Americans rowed to the south shore of the St. Lawrence.

Crysler’s Farm was a rarity in the War of 1812, being a conventional Napoleonic-era pitched battle—with a corresponding butcher’s bill. The British lost 31 killed and 148 wounded; the Americans, 103 dead, 247 wounded, and 120 taken prisoner. On November 12, Wilkinson’s main force reunited with its vanguard. Informed of Hampton’s withdrawal to Plattsburgh, Wilkinson held another council of war, which unanimously agreed to curtail the St. Lawrence campaign. By stages, Wilkinson withdrew to Plattsburgh as well.

That winter Wilkinson planned more invasions, but his only offensive, by 4,000 troops in March 1814 at Lacolle Mills, ended in defeat, court martial, and his being relieved of command. As always, he evaded conviction, but his army career was over. He died in Mexico City in 1825. In 1854 American authorities confirmed that, codenamed “Agent 13,” Wilkinson had begun spying for the Spanish in the American southwest in 1787 and remained on their payroll for several years.

Formally leaving the Army on April 6, 1814, Wade Hampton returned to South Carolina and got rich speculating in land. His plantations and 3,000 slaves made him that state’s wealthiest resident. He died in 1835, leaving a namesake and grandson who in time had a brilliant military career—fighting against the U.S. Army, as commander of the Cavalry Corps of the Confederate Army of Northern Virginia.

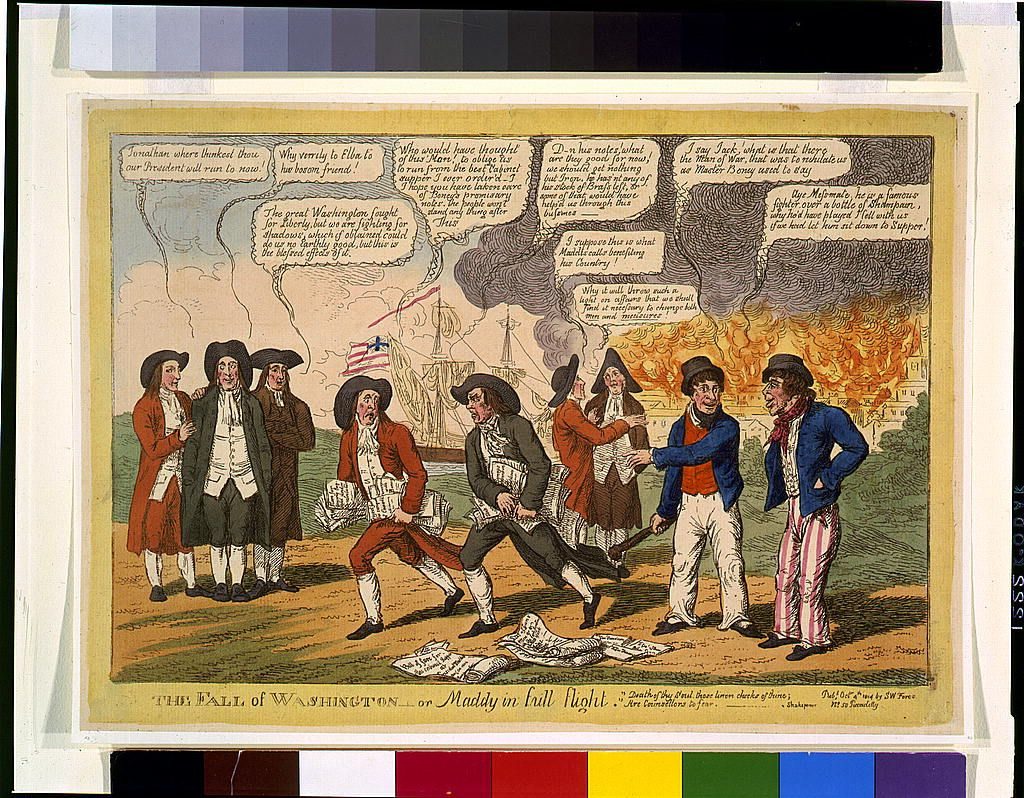

In August 1814, Secretary of War Armstrong made another brilliant mistake when he insisted until the last possible moment that the British would not attack Washington, DC. On August 24, British troops took and burned the capital. Armstrong was forced to resign his cabinet position.

Of the winning commanders, Morrison fought on until he was severely wounded at Lundy’s Lane in present-day Niagara Falls, Ontario, on July 25, 1814. He later served in India and was sailing home from a campaign in Burma when he succumbed to a tropical disease on May 4, 1826, at age 42. Charles d’Irumberry de Salaberry rose to inspecting field officer of light troops in Lower Canada. He was 50 when he died in Chambly, a suburb of Montreal, in 1829. His wartime exploits made him a local hero accorded legendary status after British North America achieved autonomy as the Dominion of Canada in 1867.

The St. Lawrence debacles get short shrift in American histories of the War of 1812. North of the border, however, Canadians call Crysler’s Farm “the battle that saved Canada” and have even higher regard for the Battle of the Châteauguay, in which U.S. Army regulars met ignominious defeat at the hands of local militiamen of English, Scottish, French, and First Nations stock—in retrospect, Canada’s first military victory.