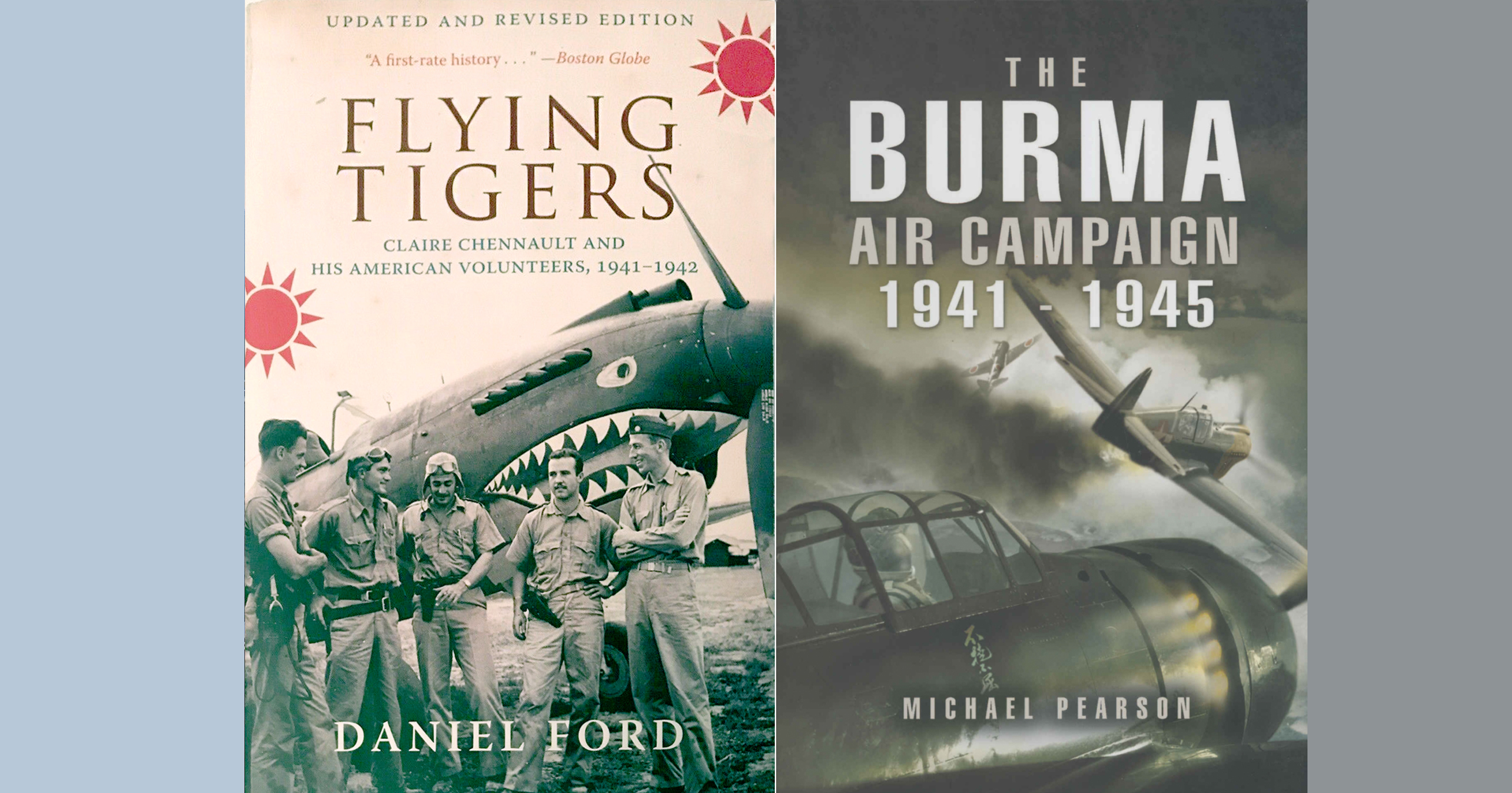

Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and his American Volunteers, 1941-1942 by Daniel Ford, Smithsonian Institution Press, Washington, D.C., 2007, $15.95.

The Burma Air Campaign, 1941-1945 by Michael Pearson, Pen & Sword Books Ltd., Barnsley, South Yorkshire, UK, 2007, $39.95.

When Daniel Ford’s history of the American Volunteer Group, Flying Tigers: Claire Chennault and his American Volunteers, 1941-1942, first appeared in 1991, his attempt to reconcile the unit’s achievements against existing Japanese records impressed some and appalled others. Flying Tigers veterans, whose $600 a month pay was supplemented by $500 for every Japanese plane they shot down, took any suggestion of a mistaken claim—even in good faith—personally, declaring Ford persona non grata at any future reunions they had. Ford himself maintained that his research was never meant to deconstruct the legendary pilots’ achievements, which he believed—even stripped of exaggeration—more than stood on their own merits.

While the Japanese army records available at the time were far from complete, more information on the enemy’s activities and losses have since come to light, and Ford was eager to compare that data with the AVG’s log. The result is an updated revision of his original book that should amend, at least in part, some of the previous edition’s discrepancies. The honest intentions behind Ford’s scholarship have also quelled some of the surviving Tigers’ fury, a suggestion in itself that the upgraded Flying Tigers is worth having.

For a short time the AVG operated from Toungoo, Burma, alongside the beleaguered Royal Air Force during the remarkable Japanese onslaught in the months after December 7, 1941. Air power played a major role in Japan’s advance to the borders of India, as well as an absolutely essential role in the Allied drive to take Southeast Asia back. British author Michael Pearson examines the evolution of aviation’s contribution to jungle warfare in The Burma Air Campaign, 1941-1945.

While air superiority and ground support are dealt with in the various battles and campaigns, a greater factor in Pearson’s book is logistics, for which the airplane became far more of a critical asset than on other fronts. The special limits imposed by Burmese terrain led to the British and American units’ being accompanied by a smaller percentage of wheeled transport vehicles, which in many cases could not follow the troops into the hills and forests. Ground forces were also reduced in number so that the available aircraft could keep them supplied, often by airdrops.

Another unusual aspect of the Burma campaign was the use of long-range strategic bombers for more tactical purposes. More often than bombing cities, Consolidated B-24 Liberators were employed by the RAF and U.S. Tenth Air Force to strike at railroad bridges and mine the Gulf of Siam—and even, on one memorable occasion, the waters surrounding Singapore, which involved a record-setting and undoubtedly grueling 21-hour round trip.

Pearson credits both sides’ achievements. Japan’s offensive featured its share of innovation and improvisation, including the use of whatever fuel and equipment the Japanese could scrounge on captured airfields to keep their planes flying. One of the most notable aspects of the Allied effort in Burma was the relatively smooth cooperation and coordination of the British and American air forces toward their common goal. The ultimate result was the reconquest of territory by 1945 that in 1943 many had doubted the Allies would ever regain.

Originally published in the July 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.