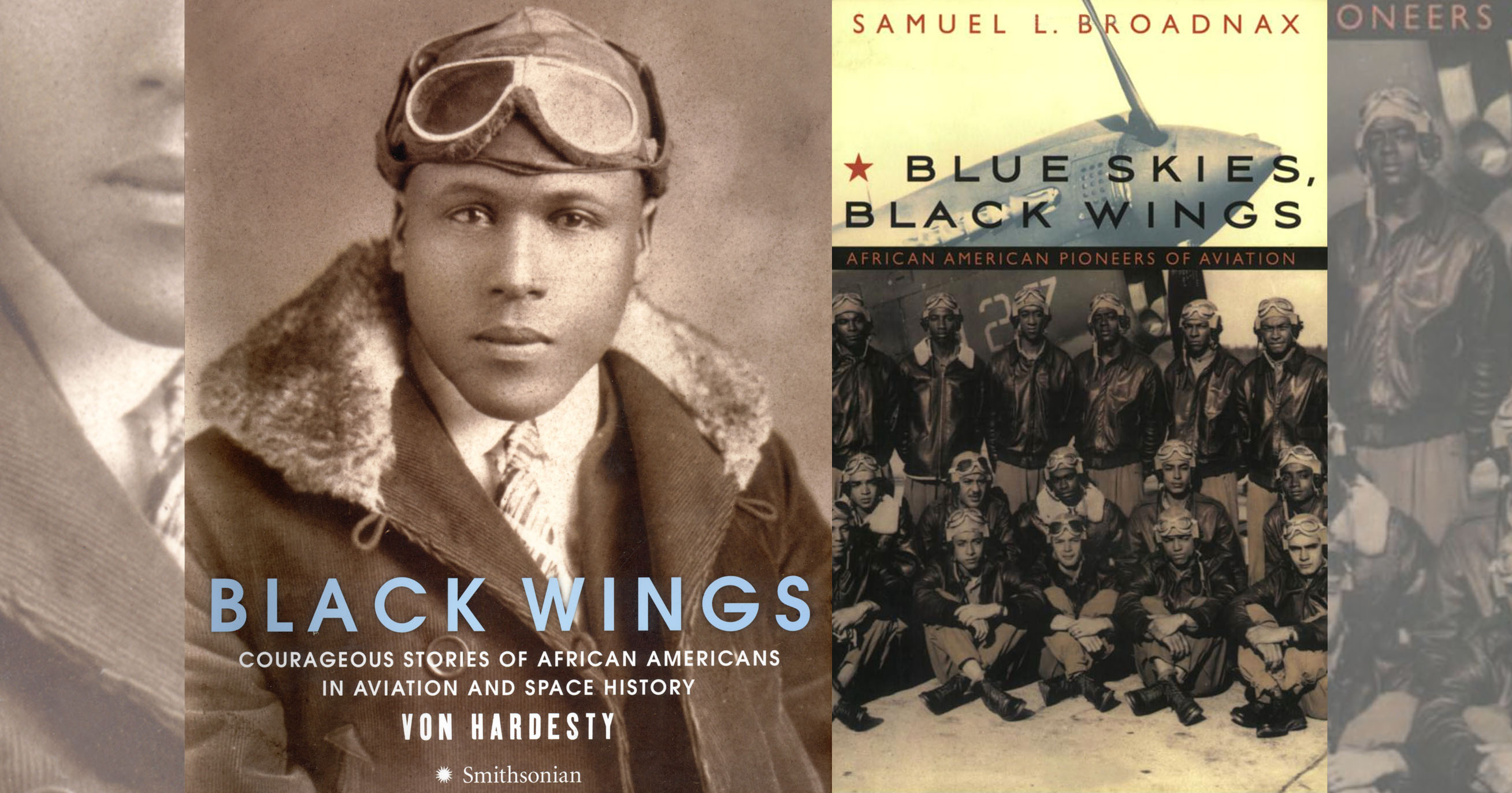

Black Wings: Courageous Stories of African Americans in Aviation and Space History by Von Hardesty, Smithsonian Books, New York, 2008, $21.95

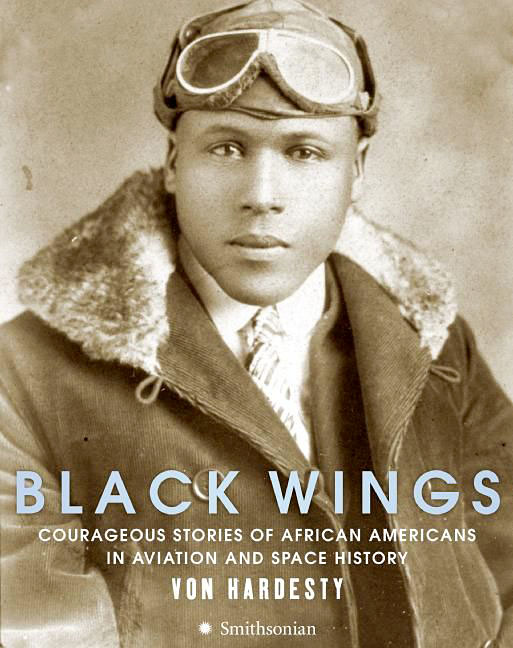

Blue Skies, Black Wings: African American Pioneers of Aviation by Samuel L. Broadnax, Praeger, Westport, Conn., 2007,$44.95

Two books provide perspective on how changes introduced through military training helped to erase the myth of race limitations. Both underscore that World War II set an important precedent, proving the color of a man’s skin was no measure of his ability to learn how to fly.

According to the official history, there were 139,000 African Americans in the U.S. Army Air Forces in August 1945, 1,533 of whom were commissioned officers. In the course of WWII, however, most pilots like me heard there were blacks flying in combat in Africa, but we usually saw them serving as truck drivers or base maintenance personnel.

Von Hardesty, a curator at the Smithsonian’s National Air and Space Museum and author or co-author of two dozen books, wrote Black Wings to supplement an exhibit on African-American airmen that he helped create. He begins with a chapter on Bessie Coleman, among the first to break the color barrier, then turns to the work of William J. Powell, foremost promoter of aviation in the African-American community in the 1930s (and author of a quasi-autobiographical work also titled Black Wings). Powell encouraged black airshows as well as the establishment of flying clubs, a trade journal and the Challenger Air Pilots’ Association.

As one might expect, Hardesty plunges into the “headwinds of prejudice” encountered by many young black pilots, who struggled to establish their right to a career in aviation but were excluded because of their race. In the 1930s a few such fliers went on to attempt air records and aviation firsts. For example, J. Herman Banning and Thomas C. Allen and the team of Albert E. Forsythe and C. Alfred Anderson were widely acclaimed in black newspapers for their transcontinental flights.

Samuel Broadnax’s Blue Skies, Black Wings is written from the standpoint of a Tuskegee Airman who won his wings in early 1945. He writes candidly of the humiliations of segregation during that era, describing the wrenching injustices forced on blacks eager to prove their flying ability and serve their country. Broadnax names several white generals and colonels who, with “craftily conceived subterfuge to keep the races separated,” deliberately flaunted Army regulations. He also details the rebellion of 101 black officers who were jailed for disobeying a direct order by a superior officer, forbidding them to enter a white officers’ club.

Both Hardesty and Broadnax recognize Colonel Noel F. Parrish, the white commander of Tuskegee Army Air Field, for his part in making the “Tuskegee experiment” a success. They also highlight the important role played by Colonel, later General, Benjamin O. Davis Jr., whose inspired leadership established a model for black officers.

Both authors bring their coverage of black aviators into the Space Age. Hardesty devotes a chapter to the military pilots who qualified as astronauts, beginning with Guion S. Bluford, the first African American to travel into space; Frederick D. Gregory, the first to command a space shuttle flight; and Dr. Mae C. Jamison, first black woman to venture into space. Broadnax also briefly surveys African Americans who have pioneered in space. But he mostly focuses on the Tuskegee Airmen, who he stresses “ripped the massive door of segregation from its hinges so that all who wished could enter.”

Originally published in the November 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.