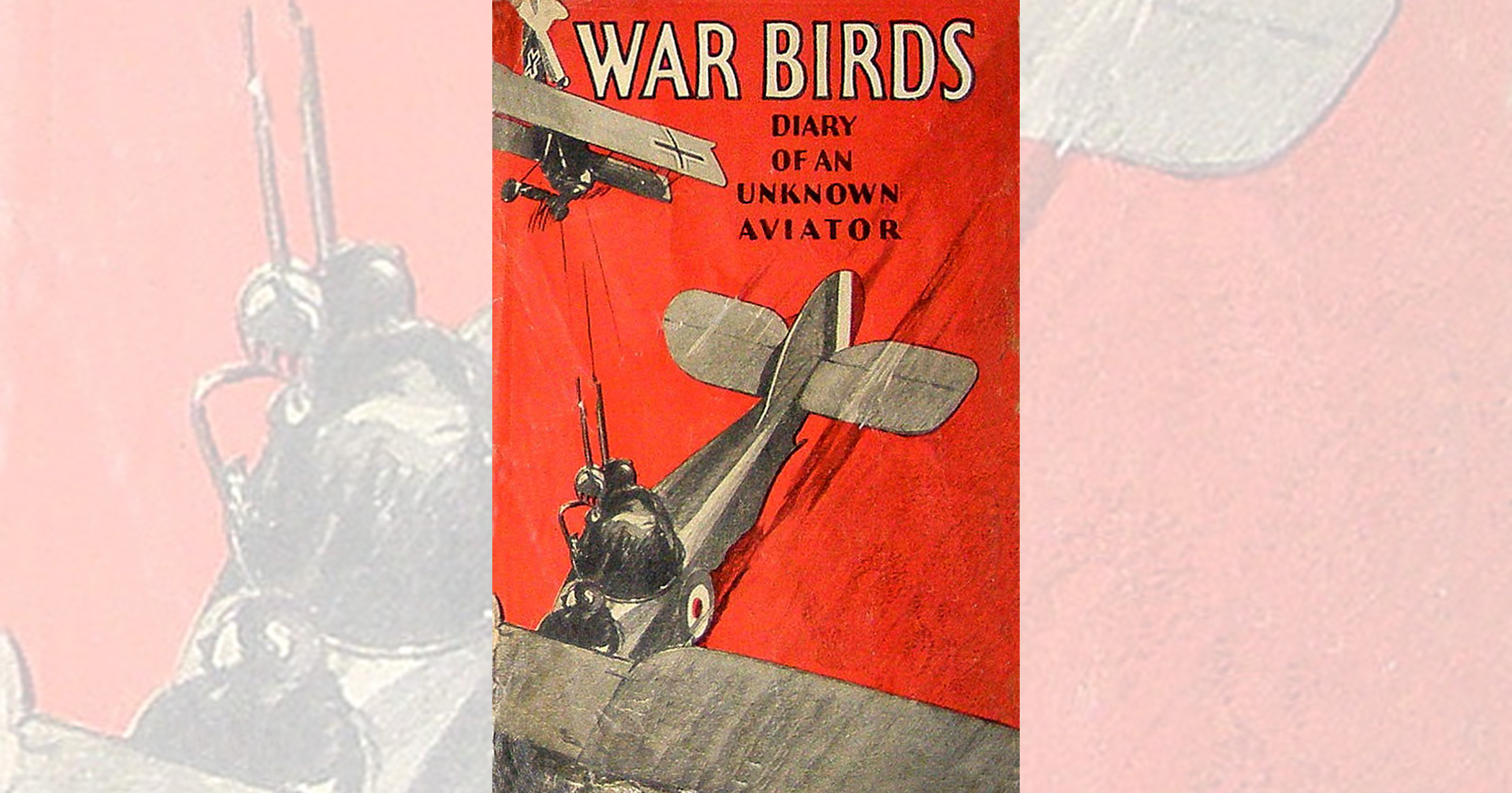

War Birds: Diary of an Unknown Aviator by John MacGavock Grider and Elliott White Springs

If James McCudden’s Flying Fury seems like the quintessentially British memoir of World War I aviation, it might be argued that War Birds: Diary of an Unknown Aviator is the prototypical American version. Originally serialized in Liberty magazine in 1926, this series of vignettes from the life of an American pilot serving in the RAF was then collected in book form. Tearing away the shiny veneer of the popular public image of the first “knights of the air,” War Birds told of clean-living, idealistic college boys adjusting to the hard realities of war and arbitrary death, resulting in fatalism, heavy drinking and womanizing. It proved to be a controversial sensation at the time.

Although it was written in the fast-moving style of a novel and often plays loose with the facts, War Birds is unique in that most of the characters are not fictional. The central figure was originally left anonymous to lend an air of mystery and universality to the story, but John M. Grider’s identity was revealed at his family’s behest by Elliott White Springs. Grider, Lawrence K. Callahan and Springs made up the book’s “Three Musketeers,” serving in No. 85 Squadron, RAF, under Major William A. Bishop. Springs, who scored 12 victories with No. 85 and later flying Sopwith Camels in the 148th Aero Squadron, U.S. Army Air Service, edited the book from Grider’s diary, combined with Larry Callahan’s and his own experiences.

Springs, who went on make a fortune running—and writing humorous and sometimes subtly risqué advertising for—his family’s Springmaid Sheets Company, was also a successful writer. His lively prose is half the reason for War Birds’ continuing popularity. The other, for serious scholars of the first air war, is his comments on the real people who turn up throughout the narrative. For example, harkening back to Flying Fury:

The Great McCudden, now Major McCudden, V.C., D.S.O., M.C., E.T.C., just back from the front to get decorated again, came into Murray’s last night for dinner, and oh, boy what a riot he caused. All the officers went over to his table to congratulate him and the women,—well, they fought to get at him just like they do at a bargain counter back home. He’s the hottest thing we have now,—54 Huns, five more than Bishop and he’s just gotten the V.C. and bar to his D.S.O. He held a regular levee. I think there are only five airmen living that have the V.C. The first thing you have to do to get it is to get killed.

The girl with him thought she was the Queen of Sheba. She started to pretend she didn’t know us. I should have reminded her where we met but I didn’t. I saved her life once.

Well, I’m not jealous. I’m going to be hot myself some day.

The book concludes with a short epilogue: “Here the diary ends due to the death of its author in aerial combat. He was shot down by a German plane twenty miles behind the German lines. He was given a decent burial by the Germans, and his grave was later found by the Red Cross.” Grider’s S.E.5a was shot down near Hamel on June 18, 1918, by Sergeant Johann Pütz of Bavarian Jasta 34. But he and all his comrades in arms, killed and surviving, live on in the pages of War Birds, which has become as much a collective term for the USAS members assigned to the RAF as “Lafayette” has come to be associated with the better-known American volunteers who flew with the French.

Originally published in the July 2009 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.