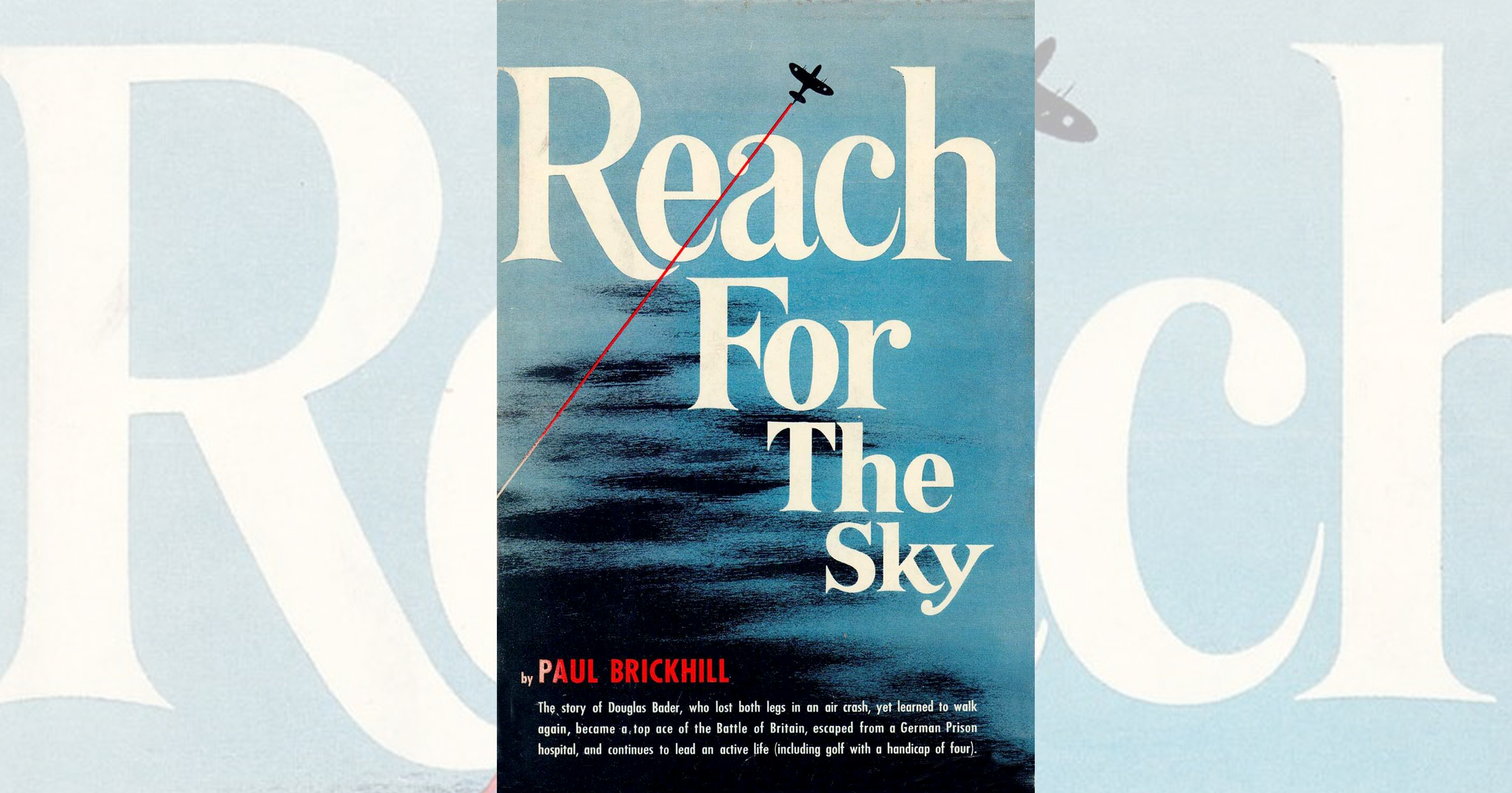

Reach for the Sky: The Story of Douglas Bader, Legless Ace of the Battle of Britain, by Paul Brickhill

Group Captain Sir Douglas Robert Steuart Bader, KBE, DSO, DFC, was a cocky young fighter pilot who lost his legs in a crash but defied the odds by going on to become a 20- victory ace. He then added luster to his story by becoming the most intractable prisoner of war held by the Germans. A gallant pilot, Bader is one of the most inspirational figures of World War II air combat.

More than an ace, he was an able fighter leader. Later in life he became a competent businessman, an inspirational speaker and a champion of the disabled. Indomitable and incorrigible, he always remained an outspoken, formidable figure, easier to admire than he was to like.

Sir Douglas wisely selected Paul Brickhill (The Great Escape, Dam Busters) as his biographer. Brickhill, himself a fighter pilot and a POW, tells Bader’s story with authenticity. He writes in an empathetic, almost affectionate manner, portraying his subject’s personal qualities, both good and bad, in the best possible light.

From his youth Bader was extraordinarily good in everything he found interesting, and only middling fair in others. An exceptional athlete, he was accustomed to being the best man playing, whatever the sport.Yet discipline was anathema to Bader, who regarded most orders as simply advisory.

Pilot Officer Bader embraced flying as he had sports, and his uncanny capability won him a slot on the RAF aerobatic demonstration team. When he and Flight Lt. Harry Day flew Gloster Gamecocks at the 1931 Royal Air Force Display at Hendon, the normally staid London Times gushed that Bader’s team “provided the most thrilling spectacle ever seen in exhibition flying…ten minutes full of the cleanest trick flying, synchronized to a fraction of a second…the most successful of the Hendon displays yet held.”

Bader’s relentless success in all areas— sports, flying, women—set him up for his fall. After his squadron transitioned to the heavier Bristol Bulldog, he could not resist when challenged to do forbidden low-level acrobatics. The Bulldog was not as responsive as the Gamecock. A wingtip caught the ground, catapulting him into a crash in which he lost both his legs, and setting the stage for his legendary comeback.

Brickhill gives ample coverage to Bader’s valiant fight, first to live, then to walk with artificial legs, followed by eight unrelenting years of effort to be restored to flying status. Only the strength of his personality enabled him to overcome his disability in the face of bureaucratic indifference.

Bader became a tactician when he was made wing commander of three Spitfire squadrons. He was officially described as a leader who “eliminated fear from his pilots,” and it was said that “His semi-humorous, bloodthirsty outlook was exactly what is wanted in war.” He was shot down, perhaps by friendly fire, on August 9, 1941, over occupied France. Despite his amicable introduction to POW status by Adolf Galland, Bader made continuous attempts to escape.

Brickhill is at his best in describing the combat of the Battle of Britain—few have done it as well. Overall his book is well worth reading or rereading, despite the fact that latter-day researchers (read: nitpickers) have spotted some minor errors in it.

I had the good fortune to host Sir Douglas during a dinner and a lengthy tour of the National Air and Space Museum in the late 1970s. As we walked along the corridors he would stop every hundred feet, ostensibly to examine a photo or an artifact, but really to catch his breath. Bader was extremely charming to all, insisting on rising to his feet to greet someone. He did so by rocking back and forth and then using his upper-body strength to literally hurl himself to a knee-clanking standing position. Even in his late 60s, when he suffered from heart troubles, his charm remained unabated, while his famed temper fortunately stayed under control. The accident that had permanently changed his appearance made him larger than life, and so he remained until his death in 1982.

Originally published in the May 2012 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.