With his army paused at Pittsburg Landing, Tenn., in early April 1862, waiting the arrival of Maj. Gen. Don Carlos Buell’s Army of the Ohio from the east, Ulysses S. Grant was confident he was on the verge of dealing a decisive blow to General Albert Sidney Johnston’s Confederate Army of the Mississippi, stationed about 20 miles away at Corinth, Miss. Union victories at Forts Henry and Donelson in February had given Grant control of the upper stretch of the Tennessee River, allowing the general to launch a forceful thrust into the Confederate heartland.

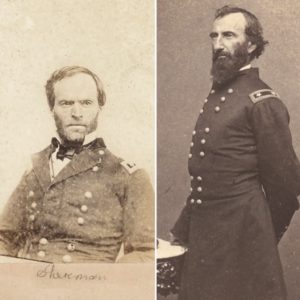

Johnston, however, stung Grant early in the morning April 6 with a strike on the Army of the Tennessee’s right flank, manned by Brig. Gen. William T. Sherman’s 5th Division and Brig. Gen. Benjamin M. Prentiss’ 6th Division. Several hours of desperate, chaotic fighting followed that initial attack, and although Johnston would be lost, mortally wounded, the Confederate onslaught continued unabated. By nightfall on the Battle of Shiloh’s first day, the Federals found themselves all but surrounded in front of Pittsburg Landing itself.

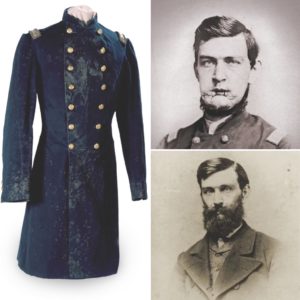

Grant famously turned the tables the following day, helped by the overnight arrival of Buell’s reinforcements, to secure an unlikely victory and another notch in a budding war record of success. For many Union soldiers, Shiloh was their first taste of true combat. Among those was Lieutenant Ephraim Cutler Dawes, 21-year-old adjutant of the 53rd Ohio Infantry, in Sherman’s division—camped near the Shiloh Church on the battle’s opening day. The 53rd, part of Colonel Jesse Hildebrand’s 3rd Brigade, had been in service for only two months.

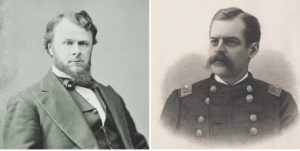

Dawes, an 1861 graduate of Ohio’s Marietta College, would be part of the one of the war’s more remarkable fighting families. His older brother, Rufus, became lieutenant colonel of the 6th Wisconsin Infantry, serving first in Northern Virginia with an all-Western brigade that would become known as the legendary Iron Brigade for its exemplary record of heroism in battle. Both brothers survived the war, but in late May 1864, Ephraim’s field service ended when he was severely wounded at the Battle of Dallas, Ga., during Sherman’s Atlanta Campaign. Rufus would be mustered out of the Army of the Potomac that August.

The following is a condensed version of Ephraim’s postwar account of his experiences that first day at Shiloh, which he penned for the Military Order of the Loyal Legion of the United States (MOLLUS). Grammar and punctuation of the original are retained.

On Friday, April 4th, there was a considerable skirmish about one mile in front of our camp. Some prisoners were captured. They were confined in Shiloh Church over night. I did not see them. Those who did reported that they claimed to be the advance of a great army, that would drive us into the river the next day.

Saturday, April 5th, was a day of rumors. Colonel [Jesse J.] Appler was very uneasy. About four o’clock in the afternoon, some mounted men were seen at the end of the field, south of our camp. The colonel sent an officer with a platoon of men through the woods to find out who they were, and to bring them in, if enemies. The men were gone some time, a few shots were heard, and the officer returned, reporting that the mounted men had escaped him and his men had been fired upon, by what appeared to be a picket line of men in butternut clothes.

Colonel Appler ordered the regiment in line and sent the quartermaster, Lieutenant J.W. Fulton, to General Sherman with this report. The quartermaster came back and said in the hearing of many of the men: “Colonel Appler, General Sherman says: ‘Take your d—-d regiment to Ohio. There is no enemy nearer than Corinth.’” There was a laugh at the colonel’s expense, and the regiment broke ranks without waiting for an order.

At seven o’clock P.M., Colonel Hildebrand sent word to Colonel Appler that General Sherman had been to his tent, and told him that the force in front of our army had been definitely ascertained to be two regiments of cavalry, two regiments of infantry, and one battery of artillery. He had directed Colonel Hildebrand to send the Seventy-seventh Ohio Regiment at 6:30 A.M., Sunday, April 6th, out the Corinth road to a point known as the See House…to support a movement of our cavalry, intended to attack and drive away or capture the part of this force in our immediate front.…

About four o’clock Sunday morning, Colonel Appler came to my tent and called: “Adjutant, get up, quick.” I hurried out and walked with him to the left of the camp. We could hear occasional shots beyond our pickets. He said he had been up all night, and that there had been constant firing. While we were standing there, our picket of sixteen men came in. They reported that they had heard a good deal of firing, and were sure that there was a large force in our front….

The colonel sent me to form the regiment; then, called me back, directed me to go to Colonel Hildebrand; again called me back, and finally sent a soldier to the brigade picket line, which was not three hundred yards away, to ascertain and report the facts. Before the soldier was out of camp, a man of the Twenty-fifth Missouri Regiment, shot in the arm, came hurrying toward us, and cried out: “Get into line; the rebels are coming!”

Colonel Appler hesitated no longer, but ordered the long roll, and formed the regiment on its color line. The only mounted officers in the regiment then were the lieutenant-colonel and the quartermaster. He sent one of these to Colonel Hildebrand and one to General Sherman with the report of the wounded man. General Sherman’s quarters were nearer to us than Colonel Hildebrand’s, and the quartermaster returned first, and said, this time in a lower tone: “General Sherman says, ‘You must be badly scared over there.’”

An officer of our regiment, just out of bed, came running to the line half-dressed, and cried out: “Colonel, the rebels are crossing the field!” pointing to the long open field south of our camp. Colonel Appler ordered the regiment to move to the left of the camp, facing south, and directed me to go at the head of the regiment and halt it at the proper point. As we filed left, one of the companies that had been sent to support the pickets came back through the brush, the captain exclaiming, as he took his place in line: “The rebels out there are thicker than fleas on a dog’s back.”

…The bright gun barrels of the advancing line shone through the green leaves. I gave the command, “Front! left dress!” and, hastening to Colonel Appler, who was in rear of the center of the regiment, said in a low tone: “Colonel, look to the right.” Colonel Appler looked up, and, with an exclamation of astonishment, said: “This is no place for us;” and commanded: “Battalion, about face; right wheel!”

At this time, about 6:45 A.M., the tents were standing, the sick were still in the camps, the sentinels were pacing their beats, the officers’ servants and company cooks were preparing breakfast, the details for brigade guard and fatigue duty were marching to their posts, and in our regiment the sutler shop was open. This order brought the regiment back through its camp. Colonel Appler, marching in front, cried out a number of times, in the loudest tones of his shrill, clear voice: “Sick men to the rear!” It is needless to add that they obeyed. The regiment halted at the brow of the elevation in rear of the officers’ tents, marched ten paces forward, faced about, and the men lay down in the brush where the ground began to slope the other way.

Two pieces of artillery of [Captain A.C.] Waterhouse’s battery [Battery E, 1st Illinois Light Artillery] took position on the right of the regiment, as it halted, and General Sherman and staff rode along its front, stopping a few paces in front of the sixth company….

General Sherman with his glass was looking along the prolongation of the line of…troops marching across the end of the Rea field, and did not notice the line on his right. Lieutenant Eustice Ball, of Company E of our regiment, had risen from a sick bed, when he heard Colonel Appler’s command, and was walking along in front of his company. I saw the Confederate skirmishers emerge from the brush which fringed the little stream in front of [our] camp, halt and raise their guns. I called to him, “Ball, Sherman will be shot.” He ran toward the general, crying out, “General, look to your right.” General Sherman dropped his glass, and looking to the right saw the advancing line of [Confederate Lt. Gen. William J.] Hardee’s corps, threw up his hand, and exclaimed, “My God, we are attacked!” The skirmishers fired; an orderly fell dead by the general’s side. Wheeling his horse, [Sherman] galloped back, calling to Colonel Appler as he passed him, “Appler, hold your position; I will support you.”

The view from the high ground where I stood at this time was one never to be forgotten. In front were the steadily advancing lines of Hardee’s corps, marching in perfect order, and extending until lost to sight in the timber on either flank. In an open space in the Corinth road a battery was unlimbering. Directly in front of the spot where General Sherman’s orderly lay dead, there was a group of mounted officers and a peculiar flag—dark blue, with a white center.

The camps of [Colonel Ralph] Buckland’s and Hildebrand’s brigades were in sight; all the regiments were in line, those of Buckland were marching forward; there were great intervals between them, for sickness had made heavy inroads in the ranks….There was a sharp rattle of musketry far to the left, on General Prentiss’ front. The long roll was beating in [Maj. Gen. John] McClernand’s camps. The Confederate battery fired, its first shot cutting off a tree top above our Company A. The two pieces of Waterhouse’s battery each fired a shot, limbered up, and returned to the battery camp; a Confederate regiment came through the line of our officer’s tents; Colonel Appler gave the command to fire; there was a tremendous crash of musketry on the whole front….The battle was fairly on.

The hour marked by the first cannon shot was seven. The first fire of our men was very effective. The Confederate line fell back, rallied, came forward, received another volley, and again fell back, when our colonel, who was behind the left wing, cried out, “Retreat, and save yourselves.”

Two or three companies on the right, whose commanders did not hear this order, stayed until they saw the remainder of the regiment going back in confusion, and then marched back, in order, to a ravine in rear of a regiment of McClernand’s division which had just come forward. Here the regiment was rallied without difficulty. General McClernand was there, and in person ordered it into position in front of General Sherman’s headquarters, designating the point where the right should rest. The regiment marched to the position indicated. The colonel [Appler] walked quietly along near the front. There were many bullets singing through the air, but he paid no attention to them. In its new place the two right companies, A and F, were separated some thirty yards from the remainder of the regiment by a deep but short ravine. Colonel Appler remained with them while I went to the left.

One of McClernand’s regiments went to our front and at once became hotly engaged. Waterhouse’s battery was firing down the ravine between our camp and the Fifty-seventh Ohio camp. A good many men in our left were shot here by a fire which they could not return because of McClernand’s regiment in our front.

As I turned to go back from the left to the right, I saw the Fifty-seventh Ohio, which had been fighting on its color line, falling back through its camp, its ranks broken by the standing tents, despite the efforts of its gallant lieutenant colonel, A.V. Rice, the only field officer with it. It seemed to me we could help them by moving the length of a regiment to our right and perhaps save the line. I ran to where the colonel was lying on the ground behind a tree, and stooping over said, “Colonel, let us go and help the Fifty-seventh; they are falling back.” He looked up; his face was like ashes; the awful fear of death was on it; he pointed over his shoulder with his thumb in an indefinite direction, and squeaked out in a trembling voice, “No; form the men back here.”

Our miserable position flashed upon me. We were in the front of a great battle. Our regiment never had a battalion drill. Some men in it had never fired a gun. Our lieutenant-colonel had become lost in the confusion of the first retreat, the major was in the hospital, and our colonel was a coward! I said to him, with an adjective not necessary to repeat, “Colonel, I will not do it!” He jumped to his feet, and literally ran away.

The sergeant-major, W.B. Stephenson, who was an old college friend, had followed me up to the line. I said to him, “Go, quick, and order each company to close up to the right.” I went to Captain Wells S. Jones, of Company A, and said, “Captain, you are in command; Appler has run away. I have ordered the regiment to close up to the right; let us help the Fifty-seventh.” He replied, “All right, get the men together; tell every company commander my order is to stay at the front, and come back as quick as you can.”

I ran down the line, stopping a moment to speak to brave old Captain [J.R.] Percy, of Company F. He swung his sword over his head and said, “Tell Captain Jones I am with him. Let us charge!”

“Wait till we get together,” I replied, and he assented. Just then the regiment in our front which had been fighting most gallantly broke to the rear. I passed across the ravine and met the sergeant-major, who said, “The men have all gone.” Where or why they went, we could not then imagine.

It transpired that our brigade commander had ridden over and ordered them back to “the road.” He did not designate what road; they expected him to conduct them, and went back until they found a road and remained there until Major [Benjamin D.] Fearing with the remnant of the Seventy-seventh [Ohio] came along, when they placed themselves under his command. I went back to Captain Jones, who had moved a little way to the right….

Bullets now began to come from our left. The battery swung around and began to fire almost to its rear. Men from Prentiss’ division were passing very rapidly behind us. The Seventeenth Illinois Regiment came up in beautiful order, and, forming on the right into line, on our left, began to fire at the Confederates who were coming now from the south-east. We continued firing almost west….

The Confederates had now captured three of Waterhouse’s guns. They swarmed around them like bees. They jumped upon the guns, and on the hay bales in the battery camp, and yelled like crazy men. Captain Jones moved our little squad, now reduced to about forty men, to join Lieutenant-Colonel Rice…who was still making a fight on the left of Shiloh Church. Of seventy men in Companies A and F, nineteen had been killed or wounded, eight or ten had gone to the rear with badly wounded men, one had fallen in a hole, and when pulled out had permission to go to the rear by the most expeditious route.

No orders had been issued in our brigade in regard to care of the wounded. No stretchers were provided. No stretcher bearers had been detailed. We had not yet learned that in victory was the only battle-field humanity. When a man was wounded, his comrades took him to the rear, and thus many good soldiers were lost to the firing line.

We joined Colonel Rice, and…with his men, drove back a disorderly line that was pursuing us, and then, with the Seventy-seventh Ohio, made a line parallel with the Corinth road, the right of this line resting near Shiloh Chapel, and the left extending toward the river.…

There was a good deal of disorder here. Every body wanted cartridges. There were three kinds of guns in our brigade and six in the division, all requiring ammunition of different caliber. Of our brigade not over four hundred men were present. The brigade commander had disappeared. During the first fight he had displayed the most reckless gallantry. At the time he rode his horse directly between the opposing lines of battle, but when the Seventy-seventh and Fifty-seventh Regiments were driven from their camps, he assumed that their usefulness was at an end, and rode away and tendered his services to General McClernand for staff duty. This line was soon broken; bullets came from too many points of the compass. The situation was aptly described by a man who was hit on the shin with a glancing ball. It hurt him awfully and he screamed out. His captain said, “Go to the rear.” As the line broke and began to drift through the brush, [he] came limping back and said, “Cap, give me a gun. This blamed fight ain’t got any rear.”

While the success of Iron Brigade Lt. Col. Rufus Dawes is well-known, the catastrophic heroics of his younger brother, Ephraim, at the Battle of Dallas, Ga., somehow tend to get overlooked by many Civil War enthusiasts. On May 28, 1864, the younger Dawes was rallying his wavering 53rd Ohio Infantry as Confederate troops closed in. Dawes was struck by a bullet to his left jaw, which, according to Private John Duke of the 53rd Ohio, “took off his lower lip, tore the chin so that it hung down, took out all the lower teeth but two and cut his tongue.” As Duke recalled: “It was the most horrible looking wound I saw during my entire army service.” Dawes survived the ghastly injury, but it ended his active military career and he underwent several surgeries over the next few months to reconstruct his lower jaw. In September 1864, Dawes underwent the most difficult of those, enduring most of a 1½-hour procedure without anesthesia after an initial dose of chloroform wore off. The wound eventually healed and he regained his speech. After the war, the 53rd Ohio members voted unanimously to present Dawes with the regiment’s national colors. —M.A.W.

On the Purdy road, two regiments of Buckland’s brigade [48th and 72nd Ohio] were in line. Our men and the Fifty-seventh fell in with the Forty-eighth Ohio. Here was more confusion than I saw at any time during the day. The troops who retained their organization were in good enough shape, but there were many disorganized men; the road was almost blockaded with teams hurrying from the battle line; a battery was trying to get into position; the Confederates charged; there was a brisk fire for a few moments. Our line gave way at all points….

There was a brass gun stuck between two small trees, apparently abandoned by all but one man who sat on the wheel horse crying. I took seven of our men and called to Colonel Rice, who took a dozen or more of his men. In a moment we broke down the saplings and released the gun….

We hurried to join the nearest troops and fell in with the Seventieth Ohio Regiment, which we now saw for the first time. I have no idea where we were, and think no one else had. All around was a roar of musketry; immediately about us was the silence literally of death, for the ground was strewn with the slain of both armies. Colonel [Joseph] Cockerill rode at the head of his regiment in a perfectly cool matter of fact way, as if it was his custom to pass through such scenes every Sunday morning. He marched the regiment along the road…several hundred yards, where I saw the sergeant-major of the Seventy-seventh Ohio Regiment in the brush near by….

In an open field on lower ground to our right was a regiment with full ranks, uniformed in blue, marching by flank to the drum beat. Their course was obliquely across the path of the Seventieth Regiment; a few moments would bring them together. It did not seem possible that a Union regiment in such condition could be coming from the battle line. I said, “They are rebels. I am going to fire on them.” He said, “They are not.” The wind lifted the silken folds of their banner. It was the Louisiana State flag!

We all had guns, and dropped to our knees and fired. The men on the road saw us, ran forward, and a rattling volley ran along the line. The Louisianians broke in disorder to their rear, and we marched unharmed past the point of danger….

A Confederate battery was now in position…the line of its fire was pretty certainly toward our troops. If we could follow it and not get shot we could surely find somebody. There was an old farm road along which we ran, falling on our faces at each report of the cannon….I think we went half a mile when I saw Colonel Hildebrand sitting on his horse by an old log barn intently watching the swaying lines and wavering banners of troops, fighting across a long open field south. “Now, we are all right,” I said to our men, and directing them to lie down in a little gully I went to the colonel, and said, “Colonel where is the brigade?” “I don’t know; go along down that road and I guess you will find some of them.”

…“Why don’t you come with us, get the men together and do something?” I said. “Go along down that road,” he answered sharply, “I want to watch this fight.”

Cannon shot were whizzing through the air, bullets were spatting against the old barn. It was not an ideal place to tarry, so calling my men we followed the road, crossed the head of a deep ravine and found Lieutenant [Jack] Henricle, a typical battle picture. His arm and shoulder were covered with blood, where a wounded man had fallen against him, his coat was torn by a bullet, his face was stained with powder, his lips were blackened by biting cartridges, he carried a gun. His eyes shone like fire. He was the man we long had sought. I said to him, “Jack, where is the brigade?” He replied, “Part of your regiment and part of ours are right down this way a little way.” I felt like falling on his neck and weeping for joy, but did not, and only said, “What time is it?” I was amazed when after consulting his watch he replied, “A quarter to three o’clock.”

We walked rapidly down the road, and soon found that portion of our regiment which had fallen back early in the morning; about two hundred and fifty strong, now under command of Lieutenant-Colonel Fulton. Near them was the Seventy-seventh Regiment, having about the same number of men….With them was a battery that had arrived at the landing that forenoon, had not yet been under fire, and had received no orders whatever. They were in front or south of the main road leading from Pittsburg Landing to Corinth, and several hundred yards west of some heavy guns, which I suppose were of the famous siege gun battery which figures so largely in all accounts of the battle. A few minutes after I reached the regiment, Captain [J.H.] Hammond, who was General Sherman’s A.A.G., rode up and gave to the commander of the battery an order which I did not hear, and then coming to us, cried out in an excited tone: “Sidney Johnston is killed! Beauregard is captured! Buell is coming! I want volunteers to go out and support this battery!”

At the command “Attention!” our men fell in, and we marched out the main Corinth road to its junction with the road running from Hamburg to Crump’s Landing; marched along it a little way to the right, then a short distance forward, where the battery went into position with our regiment on its left….The battery had hardly opened fire when it was answered by a Confederate battery with shot and shell. At first, the shells burst far behind us, and the round shot cut off the limbs of the trees above our heads. But soon another Confederate battery began to fire at a different angle, so as to partially enfilade the line….In a very short time it had disabled two guns of our battery and killed ten or twelve horses. Our battery men, however, stood up to their work until they had fired away their last round. I suppose this artillery fire lasted an hour. I do not think a single man, either in our regiment or the battery, was killed or wounded….

In about one-half hour, the firing ceased almost as suddenly as it had begun. We were not quite certain what the result had been, so, on my own responsibility, I sent a reliable man to go down the line as far as possible and find out the situation….I distributed pieces of paper…to the company commanders, to take the names of the men present….

This was the end of my first day under fire. In the light of subsequent experience, I can see many things I might have done much better, but as I recall the circumstances then existing, I have no apologies to make.

Steven Magnusen, who writes from Indianapolis, is the author of To My Best Girl: Courage, Honor, and Love in the Civil War—The Inspiring Life Stories of Rufus Dawes and Mary Gates (GoToPublish, 2020).