Tension hung over the U.S. Senate chamber on March 7, 1834, as Martin Van Buren descended from the presiding chair to confront Henry Clay. The Senate giant had just challenged the vice president to tell President Andrew Jackson about “helpless widows” and “unclad and unfed orphans” devastated by his administration’s economic policies. A packed gallery watched nervously to see how Van Buren responded. He surprised onlookers by calmly asking fellow snuff-dipper Clay “for another pinch of aromatic Maccaboy.” The Kentuckian nodded and stepped aside so Van Buren could snipe that pinch from Clay’s supply. With a sly grin, the vice president returned to his chair. For the moment tension melted and the senators of the 23rd Congress resumed their debate in what was soon being called the Panic Session, for the economic crisis gripping the country.

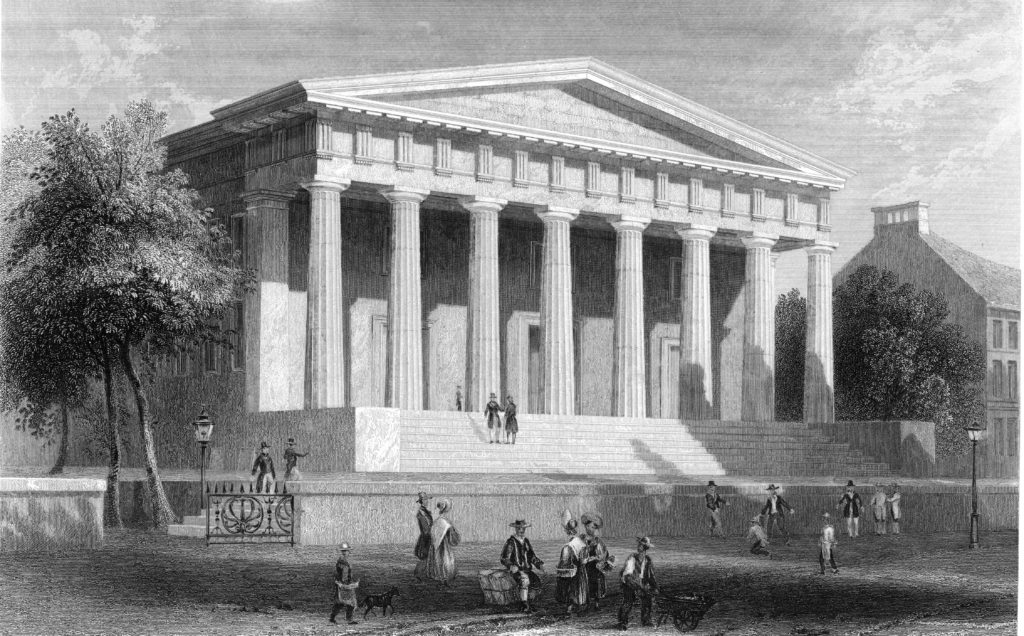

That crisis was the latest reverberation of Andrew Jackson’s ongoing war against the Second Bank of the United States. The Bank, whose main branch was on Chestnut Street in Philadelphia, had opened its doors in 1816, five years after the discontinuation of its predecessor. The War of 1812 had made clear the need for a central bank, not only to manage the nation’s finances but to generate and maintain a uniform system of currency. The Bank and its branches became the depository for government funds, disbursing money as needed to cover federal expenditures and helping to regulate a gaggle of state banks chartered since the war’s start and inclined to wild lending behavior. The Bank also held roughly one-third of the nation’s specie.

Besides serving as the government’s fiscal agent, the B.U.S. was a commercial venture. Private investors had ante’d up 80 percent of the Bank’s initial $35 million capitalization. This duality, which imposed on a public entity the responsibility of delivering profits for private shareholders, generated much criticism. Opponents argued that the Bank could not serve two masters. Much of that private investment money flowed from the Northeast and from bankers overseas, leading critics to accuse the B.U.S. of benefiting wealthy northerners and business insiders at the expense of everyday people.

The carping bore fruit almost immediately. Instead of reining in state banks, the B.U.S. emulated them, engaging in the same unsavory lending practices it had been created to stop. Just three years into the new Bank’s existence, the United States experienced its first peacetime economic depression—the Bank was not entirely at fault, but undeniably it was a factor. Demand in Europe for American crops prompted a land boom fueled by unregulated issuance of B.U.S. notes. Western B.U.S. branches loaned local banks even more money, accelerating risky purchases. Local banks extended credit to acreage-hungry farmers, creating a speculative bubble that was bound to burst and did. B.U.S. branches called in their loans, forcing local banks to do the same. Farmers who could not meet their obligations faced foreclosure. The Bank’s hand in the mess confirmed detractors’ suspicions that the B.U.S. was an unconstitutional monster favoring a select few. New leadership in the 1820s corrected many of the problems and allowed the Bank to hew to its stated purpose, but its strongest opponents remained vocal.

Among those voices, Andrew Jackson’s was one of the loudest. Jackson himself had suffered setbacks in the Panic of 1819, for which he blamed the B.U.S. His hostility intensified when rumblings from political allies based on circumstantial evidence led him to conclude that the Bank had conspired against his 1828 run for the presidency. Through his first term, Jackson made clear his displeasure with the Bank “as at presently organized” but left vague—perhaps purposefully—his intentions toward the institution. The Bank’s charter was to expire in 1836. A handful of supporters, notably Bank president Nicholas Biddle, believed Jackson amenable to rechartering. This optimism was largely ill-founded.

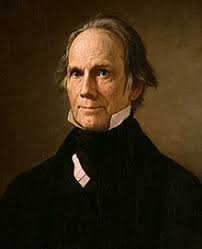

When in his third annual address to Congress in 1831 Jackson said nothing to indicate any intention to recharter, Bank advocates chose to force the issue. Chances of unseating the popular Jackson in that fall’s election appeared slim but Biddle and company, observing the Bank’s own popularity, wondered whether its influence could tip the balance. As their candidate, the National Republicans chose Bank enthusiast Henry Clay. Clay had conceived the American System, a national economic vision interweaving tariffs, federally funded infrastructure programs, and a national bank. Clay and his supporters saw rechartering the Bank four years ahead of schedule as a winning platform plank—if they could paint Jackson as the anti-Bank candidate.

Putting recharter on the ballot carried risks. A Jackson victory would signal the people’s devotion to him, imperil the Bank’s chances for future recharter, and bring down Old Hickory’s fullest wrath against it. Even so, select members of the Bank board, prominent National Republicans, and Biddle decided to submit to Congress an application to recharter the Second Bank of the United States on January 9, 1832. Enough pro-Bank sentiment existed in Congress to assure that the recharter bill passed, painting Jackson into an awkward corner. Signing the Bank bill would extend by twenty years an institution he loathed. A veto would establish himself as anti-Bank, jeopardizing his reelection chances. Jackson sought validation for the work of his first term by securing reelection by a wider margin than his comfortable 1828 victory. He had no real fear of losing the election if he vetoed the recharter bill, but history and tradition were not on his side. Previous presidents had only vetoed bills they believed unconstitutional. Jackson had concerns regarding the recharter bill’s constitutionality, but his strongest reason for vetoing stemmed from his hatred of the Bank. That summer both houses predictably passed the recharter bill. Jackson vetoed it on July 10, 1832, establishing a powerful precedent. Henceforth in pursuing legislative goals Congress no longer could count on constitutionality to fend off a presidential veto.

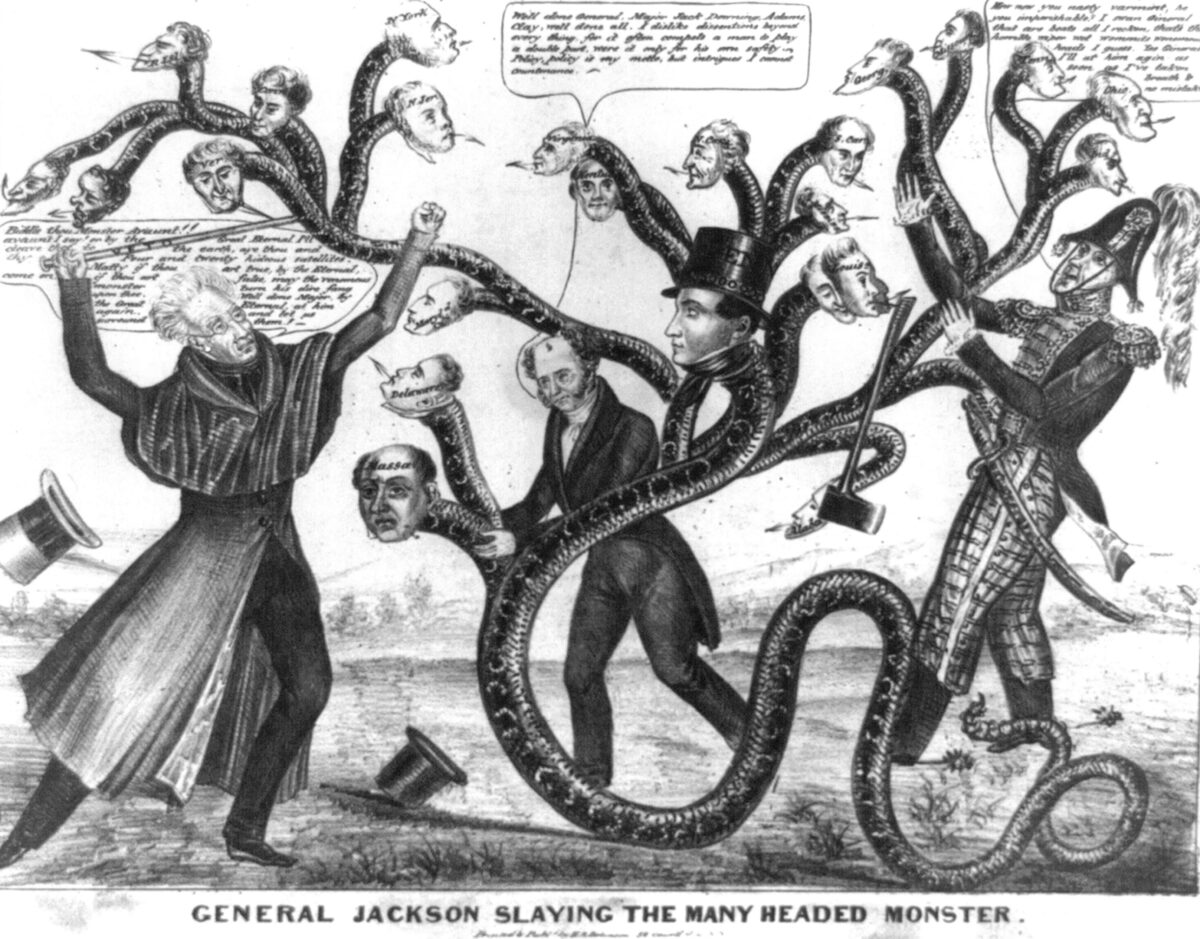

In Jackson and Clay pro-Bank forces got what they wanted—candidates with starkly defined positions on the B.U.S. Voters were left to choose between their hero and their bank, which, intent on self-preservation, engaged in the first national lobbying effort in American history. The people spoke loudly, reelecting Jackson by a crushing electoral vote margin, although his share of the popular vote shrank slightly from 1828.

Unwilling to let the Bank wither, Jackson read his victory as a mandate to destroy it. Even given his habitual exercise of executive prerogative, he recognized that he could not shut down the Bank on his own. So he set about starving it. Deprived of enough capital, the Bank could not issue enough loans or make enough investments to stay afloat. By law, federal funds generated from taxes, tariffs, and sale of western lands went in the Bank’s vaults. By 1833, such funds made up 25 to 30 percent of the Bank’s capital. Without them, the Bank would not function properly. Additionally, much of the Bank’s stability resulted from its status as the government’s fiscal agent. Divested of that role would reduce the B.U.S. to a mere commercial bank, and, thanks to the removal, a weakened one.

Under the Bank’s charter, only the secretary of the Treasury could order the removal of government deposits. Treasury Secretary Louis McLane, a pro-Bank man, was unlikely to issue such an order. Jackson reassigned McLane to head the State Department and replaced him with Philadelphian and Bank critic William J. Duane. To Jackson’s surprise, Duane resisted removing the deposits, calling the gesture “arbitrary and needless” in light of the Bank’s imminent demise. On September 18, 1833, Jackson presented to his cabinet a paper enumerating reasons for removing the deposits and taking full personal responsibility for doing so. Duane remained unmoved. Jackson fired Duane, replacing him with U.S. Attorney General Roger B. Taney; occurring as it did during a congressional recess, Taney’s appointment did not require Senate confirmation. Taney, who may have hated the Bank even more than Jackson did, issued an order on September 26 withholding all future government moneys from Bank vaults. With the federal spigot off, the B.U.S. soon would cease to be the government’s depository. The government funds would be spread among a number of chosen state banks, derided by Jackson opponents as “pet banks” due to the political considerations that went into their selection.

In anticipation of the removal order, Nicholas Biddle had acted to protect his Bank. Between August 2, 1833, through early October, Biddle, to balance against the withdrawals that were imminent, reduced the Bank’s loans from $64 million to $60 million and collected about $2.3 million in public debt. Once the removal began, he squeezed harder, in the next five months pulling $10 million more out of circulation. Trying to save the Bank, he was in effect orchestrating a panic. He hoped that tightening the money supply would cause such economic distress that Americans would blame the Jackson administration, triggering recharter as a means of rescue. Petitions and testimonials from those devastated by financial ruin inundated the Senate in the ensuing session, begging the government to restore the deposits and recharter the Bank. At a ratio of 5:1, those expressions outran the trickle of praise for the administration’s action.

That was where matters stood in December 1833, when the Senate of the 23rd Congress convened. Under the B.U.S. charter, a Treasury secretary ordering removal of government deposits was to report to Congress the reasons for doing so. Just days into the session, Taney’s report arrived and was read in the Senate chamber. In his report the secretary cited several reasons that he said had prompted the removal. For one, with its charter running out, Taney felt, the Bank needed time to wrap up its affairs. Removing the government deposits would force a slowdown of bank activities and prevent a sudden shock to the economy when the charter did expire. Taney also complained that the Bank conducted much of its business in violation of its charter. The charter stipulated that to transact Bank business a board of no fewer than seven of the Bank’s directors was required. In practice, much Bank business was done by a committee of exchange consisting of two or three Biddle appointees. This committee engaged in important Bank functions behind closed doors under clandestine circumstances that fed into the mounting suspicion regarding the Bank’s dealings. The Bank’s most egregious offense, however, was meddling in politics. For evidence, Taney cited an uptick in the Bank’s printing expenses upwards of $80,000 between 1830 and the 1832 election. In addition to the printing of anti-Jackson circulars, a portion of the spending paid salaries of printers and bought up presses, forming a pro-Bank press coalition. A hybrid public-private financial institution engaging in electioneering was an unpardonable offense and served as irrefutable proof that the Bank’s power and influence had risen to dangerous heights, Taney said. There followed one of the most contentious and consequential debates in Senate history. Besides the nation’s economy, at stake was the presidency and its holder’s relationship to Congress, to the economy, and to the people.

The debate began with Henry Clay formally requesting that Jackson submit his September 18 cabinet paper to confirm its authenticity. Clay reasoned that since the contents had appeared in the press, Jackson should confirm its words as being his. Jacksonians saw the request for what it was: a set up. Senator John Forsyth (D-Georgia) argued that Clay in effect was asking Jackson to go on the record as his statement’s author, providing grounds for impeachment. As only the House of Representatives could initiate such an accusation, Forsyth charged Clay with overstepping his authority as a senator. Jackson refused to submit or authenticate the paper.

On December 26, Clay addressed the Senate regarding what he called “a question of all time.” The Kentuckian introduced two resolutions. One formally accused Jackson of taking an unconstitutional hold over the public treasury by abusing his power of removal. The second resolution called Taney’s reasons for removing the deposits “unsatisfactory and insufficient.” Clay followed his resolutions with a three-day speech, setting in motion a debate that went on until March 28, 1834, when Clay’s resolutions came to a vote.

The debate featured lengthy speeches—one spanned four days—by about a dozen senators. Nearly everyone who spoke addressed Clay’s opening remarks directly, even when weeks separated their speeches. Senators would routinely address remarks made by multiple colleagues, creating at times a confusing dialog requiring back tracking through the written record to discern who a speaker was referencing. Some senators chose to reserve their comments to specifics regarding the Bank and its behavior. Others focused their attention on Jackson, either defending or condemning his actions. Vice President Van Buren had to restore order more than once as senators took shots at one another and twisted each other’s words.

The session’s most important arguments were political. Jacksonians attacked the process that generated the resolutions. Echoing Forsyth’s indictment of Clay’s authentication ploy, Thomas Hart Benton—Jackson’s stalwart ally from Missouri—railed against the resolutions as “a direct impeachment of the President of the United States,” assailing the opposition for seizing judicial powers. He and other Jacksonians saw the resolutions as a de facto allegation of an impeachable offense, even though the House, as stipulated by the Constitution, had made no formal charge.

Amid this rancor the debate took up constitutional topics, some not raised since the republic’s earliest days. Separation of power took center stage as anti-Jacksonians, who by session’s end were calling themselves “Whigs,” argued to rein in the chief executive. Whigs claimed that the Treasury Department answered not to the executive branch but to Congress, making Jackson’s actions against the Bank a usurpation of congressional authority. As evidence, the Whigs cited the absence of the modifier “executive” from the department’s title. Further, they argued, the treasury secretary’s responsibilities to Congress surpassed those of other department heads. Blaming the missing adjective on accidental oversight, Jacksonians countered that the Treasury had always been referred to as an executive department and its head always referred to as an executive officer.

The two sides could not even agree on what constituted the treasury and if the administration had removed money from it. Whigs insisted that once chartered, the B.U.S. had become the treasury so removing the money from its vaults without congressional approval infringed upon Congress’s authority. Jacksonians countered that the treasury was not a fixed location but rather anywhere the money was under the watch of the treasurer of the United States. Shifting the government funds from the B.U.S. to state banks did not change that they could not be disbursed without the treasurer’s signature. Therefore, Jacksonians argued, the money was still in the treasury despite being jettisoned from the Bank’s vaults. Jackson had done nothing illegal.

The Senate also scrutinized the president’s control over his cabinet and his use of removal to exercise that control. Jacksonians contended that the Constitution explicitly granted the president sole authority to oversee the faithful execution of the laws. This justified any measure Jackson took, including removing recalcitrant officers, they argued. By this line of reasoning “good government” required a singular executive vision that the president was duty-bound to establish and maintain. If executive officers could act upon their individual designs, the Jacksonian line went, government would become disjointed and inefficient. The Whigs predictably rejected this claim. Ignoring the fact that the 1stCongress had settled the question, Ohio Whig Thomas Ewing went as far to argue that the president needed Senate approval to remove officers. Most other Whigs, conceding that Jackson had authority to remove his treasury secretaries, said this particular use perverted the founders’ intentions.

Clay declared that the mechanics of presidential removal, formalized narrowly in 1789 by Vice President John Adams’ tie-breaking vote, required fresh examination. Toward the end of the debate Clay proposed additional resolutions intended to curb the president’s power to remove officers and requiring that he obtain Senate consent to do so. Tabled without serious debate, these resolutions died a quiet death. However, the Whig leader’s desire to revisit a matter settled by the 1stCongress reveals a distinct level of concern with where Jackson had taken the presidency.

Dissections of Clay’s resolutions often shoved aside discussion of the Bank and its fate, by now a given even among Whigs. The resolutions effectively were seeking to stand in for voters in repudiating the Jackson presidency and its expansion of presidential power. Peleg Sprague, a little-known Whig senator from Maine, delivered the most emphatic disavowals of Jackson’s tenure. Removal of the deposits, Sprague said, illustrated only the latest example of Jackson’s exercise of a design to “accumulat[e] power in one great and all-absorbing reservoir” placing “the whole statute book at [his] mercy.” Reciting a litany of alleged Jackson transgressions, Sprague exploded, “[a]nd this is republicanism!!!” His outburst encapsulated the Whigs’ deepest fears; namely, that Jackson would succeed in subjugating the legislature and judiciary. Senate Whigs saw in the Panic Session a final chance to reestablish congressional dominance over the federal government.

Despite initial promise, those efforts proved futile. On March 28, 1834, Whigs and pro-Bank Democrats voted to adopt both Clay resolutions. The first, censuring Jackson, passed 26-20, with four members disregarding state legislatures’ instructions to vote no. Two weeks after the vote, Jackson submitted a formal protest to the Senate, voicing his disgust with the proceedings. Jackson, declaring himself the people’s tribune, said his reelection constituted a popular mandate to destroy the Bank. He took up supporters’ claim that the resolutions amounted to an unconstitutional pseudo-judicial proceeding. Jackson reminded senators that had the charade been an actual impeachment trial, it would have failed, not having achieved the two-thirds vote required for conviction—even despite the votes of those four rogue senators.

As winter gave way to spring, opinion slowly turned against the B.U.S. and the Whigs. Struggling businessmen came to the president seeking relief but Jackson shrewdly flipped the script, convincing them that Biddle’s and the Bank’s market manipulations were causing their troubles. By May 1834, Biddle had to reverse course and end his manufactured panic without securing restoration of the deposits or recharter. The more Jackson-friendly House of Representatives, trying to justify Jackson’s actions, adopted anti-B.U.S. resolutions. By late spring, Jackson and company had forced a complete 180°. The congressional session had begun with Jacksonians reeling, struggling to counter accusations of usurpation, abuse of power, and a subsequent economic collapse. By session’s end, public support for the B.U.S. had evaporated and Jackson once again was a hero, adored this time for conquering a Senate hell-bent on reversing the people’s will. The final blow came in 1837, when a three-year crusade led by Benton succeeded in expunging Jackson’s censure from the record. The 24-19 vote to reverse Clay’s resolution came just weeks before Jackson left office. The only official condemnation of the president’s actions now sit harmlessly, forever obscured by the words scrawled by Senate Secretary Ashbury Dickens: “Expunged by the order of the Senate, this 16th day of January, 1837.”

The Panic Session and its larger context of Jackson’s campaign against the Bank had profound effects. The economic impacts, though, were minimal. Deposit banking continued and the economy recovered, at least until 1837, when another depression, largely attributed to international conditions, hit. Congress established an independent Treasury to manage the government’s finances in 1840. In 1841 the Whigs repealed that law, but it was reinstated in 1846 and its creation continued until 1913, when the Federal Reserve replaced it.

The episode’s lasting impacts were instead political. The conflict crystalized a random assortment of anti-Jackson figures into a cohesive party, the Whigs, that vied with the Democrats for two decades. Also in the political column were the changes the conflict wrought on the presidency. When Jackson vetoed the Bank recharter bill for personal reasons, he transformed the veto from a safeguard against unconstitutional laws to a weapon of presidential will. By couching his reelection as a popular mandate to remove the deposits and destroy the Bank, Jackson established electoral success as a go-ahead to take specific executive action. And in declaring himself the people’s tribune Andrew Jackson altered the job of presiding over the nation. No longer a detached presence watching over the country, the president now wore the mantle of defender of the public interest.

Michael Trapani has taught American history in central New Jersey for fifteen years. His book, Panic in the Senate: The Fight Over the Second Bank of the United States and the American Presidency, was recently published by Algora Publishing. He resides in Rockaway, N.J., with his wife, Kelly, and two daughters, Addison and Everly.