Abraham Lincoln’s critics were vitriolic, but at least he didn’t have to deal with them in a daily twitter feed.

This past summer, a beleaguered Barack Obama invited a new wave of criticism—if such criticism really surprises him or us anymore—by ill-advisedly comparing himself to Abraham Lincoln. The subject, ironically enough, was criticism itself.

“Democracy is always a messy business in a big country like this,” Obama declared in Decorah, Iowa. “Lincoln, they used to talk about him almost as bad as they talk about me.”

Not surprisingly, the comment unleashed a firestorm of disapproval. Weighing in were Reagan administration veterans (“More grandiose than narcissistic,” cried former aide Eric Denzenhall. “It’s equating any form of push-back with some sort of giant historical crime”); columnists in the conservative press (“He has it easy compared to the hatred thrust upon Abraham Lincoln,” declared John J. Miller in the New York Post); and also, for the first time, previously sympathetic historians. Alvin Felzenberg of the University of Pennsylvania called Obama’s remarks “laughable,” “hysterical,” “vain and self-absorbed,” adding, “You couldn’t print things today they said about Lincoln.”

Not surprisingly, the comment unleashed a firestorm of disapproval. Weighing in were Reagan administration veterans (“More grandiose than narcissistic,” cried former aide Eric Denzenhall. “It’s equating any form of push-back with some sort of giant historical crime”); columnists in the conservative press (“He has it easy compared to the hatred thrust upon Abraham Lincoln,” declared John J. Miller in the New York Post); and also, for the first time, previously sympathetic historians. Alvin Felzenberg of the University of Pennsylvania called Obama’s remarks “laughable,” “hysterical,” “vain and self-absorbed,” adding, “You couldn’t print things today they said about Lincoln.”

Even Pulitzer-winning Columbia University historian Eric Foner piled on. Pointing out that criticism of Lincoln “was even more vitriolic than what you see about Obama,” Foner opined, “Obama is a guy who has a thin skin and does not take criticism well.”

Let’s be accurate. Lincoln was indeed called far worse names (although, to be fair, he was never the subject of racism or challenges to his citizenship). Some of them were indeed ugly, if not exactly unprintable in modern family newspapers, as Felzenberg suggested.

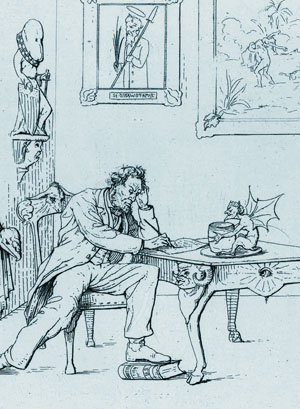

Lincoln was teased, mocked, taunted and abused by unfriendly editors and political critics alike. Judging the level of vitriol is a subjective business. Lincoln called himself the most abused man in Washington, and he was right. One attack—from a customarily friendly

editor—made him feel like “a dog,” though most of the time he brushed off criticism with a smile.

But it’s not difficult to compare the media of the Lincoln era with today’s. The fact is, modern presidents are subject to, or the subject of, so much criticism, so relentlessly and in so many forms and formats, the daily press of the Civil War era looks placid, at least in terms of volume and frequency. It’s not that we’re ruder now, or that today’s leaders are more deserving of attack. It is simply that formats such as Facebook, Twitter, 24-hour TV news and shock jock talk radio offer so much assaultive commentary to so many so frequently. Even Lincoln’s skin might have bruised had he faced a daily ripping from news and talk show hosts, not to mention the uncensored commentary that fills the ever-ready and frequently uncivilized blogosphere.

Lincoln may have laughed off most hurtful assaults—at least those he heard about. Remember, in a time when only major newspapers might be available for daily reading (and pouting) at the White House, Lincoln certainly never heard or read the now-famous attacks launched against him in the South or in smaller Northern towns and villages. Distribution of Southern newspapers was generally banned along with other “commerce.” Adalbert Volck’s withering etchings remained largely unseen until after Lincoln’s death.

Even General McClellan’s rude reference to Lincoln as a “gorilla”—now part of virtually every biography—was at the time known only to the commander and his wife.

Obama may indeed be criticized more often, but he would do well to take some lessons from Lincoln’s fabled forbearance. “As a general rule,” Lincoln said only days before his assassination, “I abstain from reading the reports of attacks upon myself, wishing not to be provoked by that to which I cannot properly offer an answer.” A year earlier, he responded to another critic by observing: “Dogs will bark at the moon, but I have never heard that the moon stopped on that account.”

Provoked he may well be, but barring a catastrophe, a president can be “stopped” only by voters at the polls. Lincoln endured a disastrous midterm election upheaval and entered his re-election year facing likely defeat. As the Civil War president taught himself and his critics, it’s not over till it’s over.

Not that criticism did not cause Lincoln his own share of pain. Much has been made of his thick skin, but as a young politician, he frequently responded to rebuke in kind and with relish. Later, when he lost the 1858 Senate race to Stephen A. Douglas, he famously admitted that he was too hurt to laugh and too big to cry. Conversely, when editors praised him for issuing the Emancipation Proclamation, Lincoln confided to his vice president, Hannibal Hamlin, “Commendation in newspapers and by distinguished individuals is all that a vain man could wish.”

Of course, the mature Lincoln was wise enough to share such feelings only with friends and subordinates—not journalists. Had Obama admitted he is sometimes close to tears over criticism, or finds his vanity tickled by praise, the commentators’ howling would last until the election.

Another Lincoln-admiring president, George W. Bush, once asked me face-to-face how much criticism Abraham Lincoln really endured. In particular, was he ever criticized for saying he was too often criticized?

And then, before I could answer, Bush reminded me that Lincoln had his own way of dealing with critics who assailed administration policies—he closed down newspapers and imprisoned editors. “I never shut the New York Times,” Bush reminded me, adding with a wink, “much as I’d like to.”

Harold Holzer chairs the Abraham Lincoln Bicentennial Foundation.