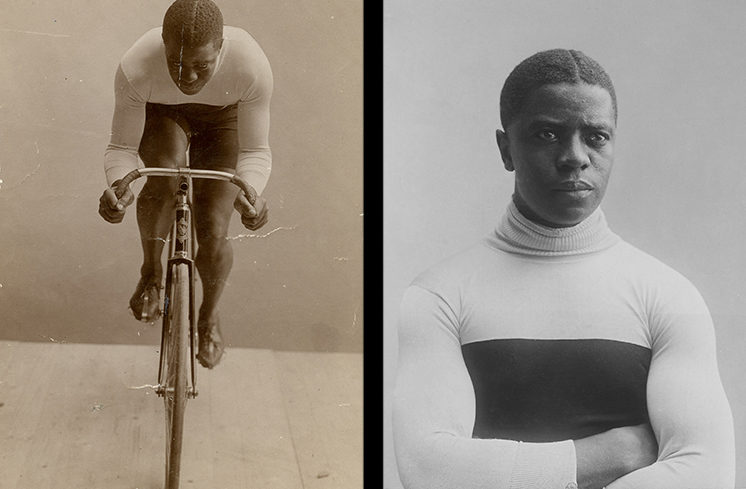

“Major” Taylor was the best bicycle rider of his time, but his career was badly undermined in the Jim Crow South

The World’s Fastest Man: The Extraordinary Life of Cyclist Major Taylor by Michael Kranish, Scribner, 2019; $28.00

What a ride. Besides explicating the origins and impact of competitive cycling in the late 1800s and early 1900s, Fastest Man unblinkingly examines how racism drove and dogged America’s first Black sports hero, Marshall Walter “Major” Taylor. Author Michael Kranish delivers a compelling and detailed chronicle of a life worth knowing.

Taylor was born in 1878 in Louisville, Kentucky. Father Gilbert, a Civil War veteran, and mother Saphronia moved their family to Indianapolis, Indiana, where Gilbert hired on as a coachman for a wealthy white family, the Southards. Befriended by their son, Daniel, Marshall lived with the Southards from ages 8 to 12, afforded all his pal’s opportunities, including academic tutoring and a bicycle—a career-founding gift. Marshall took fervently to two-wheeling, riding hard and well and perfecting stunts. A bicycle shop owner hired him to work at his store and show off his skills. His habit of wearing one of his father’s Union Army jackets earned the youth the nickname “Major.”

Taylor was born in 1878 in Louisville, Kentucky. Father Gilbert, a Civil War veteran, and mother Saphronia moved their family to Indianapolis, Indiana, where Gilbert hired on as a coachman for a wealthy white family, the Southards. Befriended by their son, Daniel, Marshall lived with the Southards from ages 8 to 12, afforded all his pal’s opportunities, including academic tutoring and a bicycle—a career-founding gift. Marshall took fervently to two-wheeling, riding hard and well and perfecting stunts. A bicycle shop owner hired him to work at his store and show off his skills. His habit of wearing one of his father’s Union Army jackets earned the youth the nickname “Major.”

Working at Indianapolis bike shops and entering local races, Major met Louis “Birdie” Munger. The former high-wheel racer and bike builder became Taylor’s coach and lifelong mentor. Taylor moved to Worcester, Massachusetts, rolling up record-breaking times as an amateur 1892-95. In 1896, now 18, he turned professional, debuting in a half-mile handicap race at New York’s Madison Square Garden.

Taylor hit it big on the pro circuit—Theodore Roosevelt was a fan—variously hailed as the “Worcester Whirlwind,” “Black Cyclone,” “Ebony Flyer,” and “Black Zimmerman”—the last because Major Taylor idolized fellow rider Arthur Zimmerman for his two world records and relentless training. In 1899 in Montreal, Taylor became the first African American to win the World Sprint Championship, followed by a string of cycling triumphs worldwide.

But the Ebony Flyer could not outrun racism, especially in the American South, where, in keeping with Jim Crow oppression, promoters barred mixed-race events and white cyclists refused to ride against him, even attacking him physically. Foreshadowing the grit of Jesse Owens, Jackie Robinson, and later generations of Black Americans determined to claim their place in national life, Taylor kept his focus. Upon his retirement in 1910 he ventured into business dealings that soured. His family disintegrated. Unknown to his wife and daughter, Taylor died in 1932 in a Chicago charity ward and was buried in a segregated pauper’s grave. Reinterred properly in 1948—one sponsor of his stately memorial at Cook County’s Mount Glenwood Cemetery was Schwinn Bicycles—he sank from public awareness until the 1980s, when renewed American interest in competitive cycling brought him a revival of reputation.

This post contains affiliate links. If you buy something through our site, we might earn a commission. Thanks!