Through a Howling Wilderness: Benedict Arnold’s March to Quebec, 1775

by Thomas A. Desjardin; St. Martin’s Press, 2006

A 600-mile March through wilderness. Whitewater rapids that smashed boats to smithereens. Swamps whose winding trails petered out into bogs. Spoiled rations, then none at all. Dog soup and candle stew. A hurricane followed by a flood. Cold so bitter that wet clothes “froze a pane of glass thick.” And finally, a mutiny.

The Continental Army’s march to Quebec in the autumn of 1775 remains one of history’s most agonizing and amazing. Even the British admitted that it would “ever rank high among military exploits” because of “the boldness of the undertaking and the fortitude and perseverance with which the hardships and great difficulties of it were surmounted.”

Those “hardships” and “fortitude” should have immortalized this anabasis. Instead, both the march and the subsequent attack on Quebec are virtually forgotten. Perhaps that’s because the eventual traitor Benedict Arnold conducted them, or perhaps it’s because they ended in failure. Now comes Thomas A. Desjardin’s Through a Howling Wilderness, describing the campaign’s two deadly battles: that between the Continental and British armies over the city of Quebec, and the even fiercer one between indomitable human will and implacable Mother Nature. Both tales are riveting, and Desjardin, site historian for the state of Maine, enlivens them with plenty of quotes from the participants and anecdotes about their travails and the people they encountered. The author, who lives near the march’s route, uses his extensive knowledge of the region and his engaging writing skills to transform the very landscape into a major character in the tale.

Before he became a traitor, Arnold had become a hero—one of the Patriots’ greatest, in fact. In May 1775, he and Ethan Allen captured Fort Ticonderoga with its 100 cannons from the British. Arnold’s resulting reputation for guts, gumption and military expertise made him the obvious choice that summer to command the second column in a two-pronged invasion of Canada.

But we do a disservice in calling it an “invasion.” All the Patriot participants, from the commanders to the men in the ranks, considered themselves liberators, not invaders. Canadians were suffering the same insults to their liberty as the colonists to the south. If they longed to be free, the Patriots would help by loosening the Redcoats’ hold on Canada—but only if the Canadians wanted them to. That proviso links the northern campaign to modern headlines: Should America invade other countries and compel their citizens to adopt governments we prefer?

Today’s politicians might shout “Yes!” But our 18th-century leaders answered differently. The Founding Fathers understood that liberty cannot be imposed from without; people have to prize it enough that they are willing to fight—and even to die—for it. That realization underlay all of Colonel Arnold’s plans and preparations. General George Washington’s orders stressed that Arnold was to discover “the real sentiments of the Canadians towards our Cause.” If they were “averse to it and will not co-operate or at least willingly acquiesce,” Arnold was “by no Means to prosecute the Attempt,” though the “present enterprise” was “of the utmost consequence to the interest and liberties of America.”

And “of the utmost consequence” it certainly was. The Continental Army in September 1775 was already suffering the privations that would continually characterize its existence. There were never enough men, and even those few were never properly outfitted. If they had muskets, they lacked powder; if they had waistcoats, they lacked breeches; if they had rations, the bread was not only wormy but forsaken by meat or butter and—inconceivably to troops then—they even lacked rum. Washington looked to Canada for a remedy: “I must beg…the Wants of the Army here, which are not few, and if they cannot in some Parts be supplied by [Canada], I do not Know where else I can apply.” Despite so overwhelming an incentive, neither Washington nor Arnold planned to plunder Canada. Arnold wrote a friend that his detachment would “frustrate the arbitrary and unjust measures of the [British government] and restore liberty to our brethren of Canada.”

Through a Howling Wilderness concentrates on the astounding nuts and bolts of this attempt to restore that liberty. First, Arnold had to move 1,100 men from Cambridge, Mass., several hundred miles to Quebec City. That would have been daunting enough had he used one of the two usual routes of the time—along the Atlantic coast to the St. Lawrence River, or inland, up the Hudson River to Lakes George and Champlain. The British navy, however, patrolled the coast, which ruled out the first option. And General Richard Montgomery was then traveling the Hudson River route with a detachment on its way to Montreal, making the second option also unavailable to Arnold.

As the other pincer in the advance on Canada, Arnold would have to march his men through the wilderness of Maine via the Kennebec River, even if it meant going upstream against frenzied whitewater rushing away from Quebec.

For six weeks, those 1,100 troops endured unimaginably hard conditions in a wilderness that was no primeval paradise. This treacherous tract had roaring rivers to drown men, marshes that sucked at their legs and sent them sprawling, and dense forests and undergrowth impenetrable to soldiers or even sunshine. Everything needed to sustain life had to be floated over the whitewater, lugged through the swamps and pushed through the brambles. On October 14, just a few weeks into the odyssey, army surgeon Isaac Senter noted: “The army was now much fatigued, being obliged to carry all the bateaus [lightweight, flat-bottomed boats], barrels of provision, warlike stores, &c., over on their backs through a most terrible piece of woods conceivable. Sometimes in the mud knee deep, then over ledgy hills, &c….”

Between the hard going and faulty maps, starvation soon descended. Rations were slashed, again and yet again. Soldiers sometimes shot moose or caught trout, but the army’s noise and smell scared most game away. The men were reduced to eating tallow candles, and according to one account, “old moose-hide breeches were boiled and then broiled on the coals and eaten.” Surgeon Senter claimed they had to resort to eating the leather from shoes and cartridge boxes, pomatum and shaving soap, as well as three dogs accompanying the expedition. Captain Henry Dearborn mourned, “They ate every part of [my Newfoundland dog]…not excepting his entrails; and after finishing their meal, they collected the bones and carried them to be pounded up, and to make broth for another meal.”

Hunger might seem their most merciless enemy, but at least one soldier lamented that “what we most dreaded was the frost and cold from which we began to suffer considerably.” It was October, which is to say winter, in Maine. The men were usually immersed in water, whether pulling their boats through the Kennebec’s fury or slogging through swamps. And the weather’s brutality increased. A hurricane killed a few troops with falling trees; one night their campsite flooded; several nights, snow blanketed an army lacking other cover. It’s hardly surprising that half the men mutinied and marched home. Incredibly, the rest struggled on.

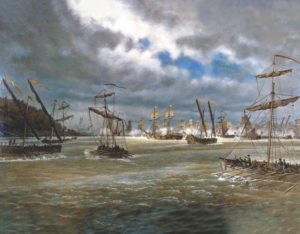

Once having reached Quebec, they endured another six weeks of savage weather, though they were better fed and clothed. General Montgomery’s men, fresh from freeing Montreal, joined them, and on the last day of 1775, the combined columns assaulted Quebec. Montgomery was killed, Arnold wounded and, tragically, most of the troops who had endured so much to “restore liberty” to Quebec, who had dined on dog and waded whitewater, were captured. They spent the next months imprisoned in the city they had hoped to free.

The courage, zeal and heroism of Benedict Arnold and his men deserve far more reverence than they have received. Desjardin’s Through a Howling Wilderness sparkles in tribute to them.

Originally published in the August 2006 issue of American History. To subscribe, click here.