The Civil War was an environmental catastrophe for the Confederacy and loyal states where armies fought and encamped

BY THE SUMMER OF 1863, the war’s profound impact on environmental resources stood out across much of the Confederacy and in loyal states subject to military activity. The mere presence of an army disrupted natural patterns and agricultural rhythms. Wherever a large force camped for any length of time, thousands of campfires resulted in the destruction of many acres of forests, substituting moonscapes for previously lush vegetation. Even one night’s appearance by an army, whether friendly or hostile, could bring the loss of a farm’s fencing, crops, and animals. As the war progressed, much of the Confederacy’s heartland experienced catastrophic damage from armies bent on destruction or simply seeking food and fodder for soldiers, as well as for the thousands of horses and mules that labored alongside them. When armies went into winter quarters, the environmental dislocation escalated in any area within reach of troops seeking firewood, building materials for huts, food, and other items.

[divider_flat]William Tecumseh Sherman and Philip H. Sheridan most often come to mind when considering how armies wreaked havoc on Confederate agriculture and the animals and structures that supported it. “I have destroyed over 2,000 barns filled with wheat, hay, and farming implements,” Sheridan famously reported from the Shenandoah Valley in 1864, “over 70 mills, filled with flour and wheat; have driven in front of the army over 4,000 head of stock, and have killed and issued to the troops not less than 3,000 sheep.” Sherman spoke more concisely in a letter to his wife near the outset of the Atlanta Campaign: “We have devoured the land and our animals eat up the wheat & corn fields close—”

Three witnesses, however, provide testimony about environmental changes wrought long before Sherman’s and Sheridan’s operations. In late June 1863, British observer Arthur James Lyon Fremantle traveled through central Virginia with Lee’s army and wrote about the countryside around Sperryville, a village near the eastern slope of the Blue Ridge Mountains. The nearby presence of two armies for more than a year—there had been no battle in the area—left the region “completely cleaned out.” Many acres lay “almost uncultivated, and no animals are grazing where there used to be hundreds. All fences have been destroyed, and numberless farms burnt, chimneys alone left standing.” Fremantle concluded, “It is difficult to depict and impossible to exaggerate the sufferings which this part of Virginia has undergone.”

Two Union accounts demonstrate that Middle Tennessee presented a comparably bleak picture. Known in the prewar years for its agricultural bounty, the region had been overrun by Federal armies in 1862 and subjected to intense foraging. A cavalryman, writing in April 1863, adopted language similar to Fremantle’s: “It is really sad to see this beautiful country here so ruined. There are no fences left at all. There is no corn and hay for the cattle and horses, but there are no horses left anyhow and the planters have no food for themselves.”

The cavalryman in Tennessee would have been particularly alert to the absence of horses. The contending sides probably used close to 1.1 million horses and 750,000 mules—for the cavalry and artillery, to pull supply wagons and ambulances, and to support construction or repair projects associated with campaigning. Losses among horses and mules cannot be determined with precision, but they were terrible. Diseases swept through horse depots and armies, and claimed thousands of victims.

In the fall of 1863, the Army of the Cumberland alone, while besieged in Chattanooga, lost 10,000 animals dead or so disabled they could no longer work. The following spring, Union armies ordered that all livestock abandoned on the march should be shot to prevent Rebels from capturing and returning them to service. Charles Francis Adams Jr., a Union cavalryman whose great-grandfather and grandfather had been presidents of the United States, spoke to how horses suffered. “The air of Virginia is literally burdened today with the stench of dead horses, federal and confederate,” he informed his mother in May 1863: “You pass them on every road and find them in every field, while from their carrions you can follow the march of every army that moves.”

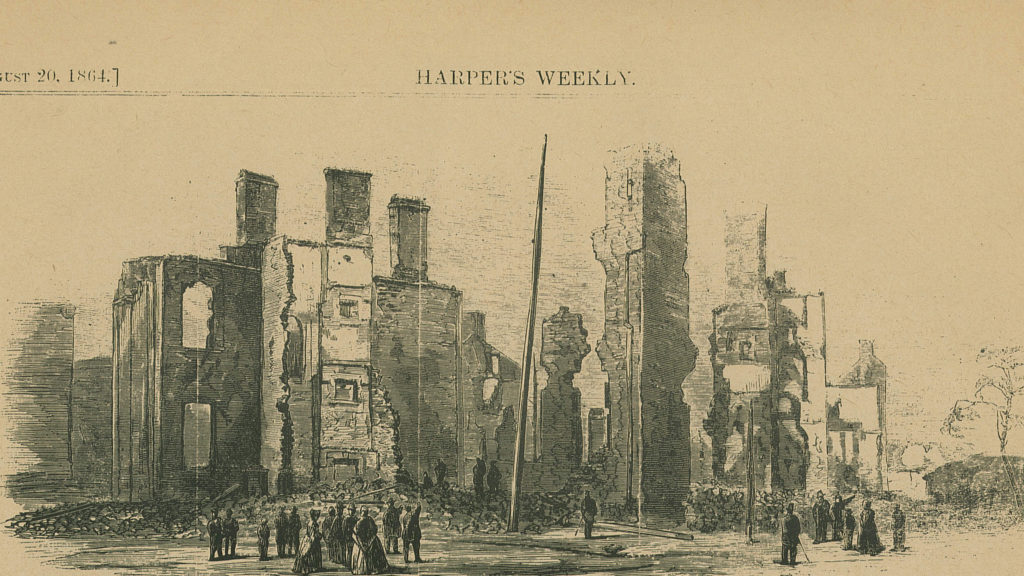

Private homes and outbuildings, as well as mills, factories, railroad facilities, and other structures more directly tied to the war efforts, also suffered damage or destruction. Among the first was Judith Henry’s modest home on the First Bull Run battlefield, which stood near the center of combat on July 21, 1861, and by the summer of 1862 had been reduced to shambles. Fredericksburg, Charleston, Petersburg, Vicksburg, Atlanta, and other Confederate towns and cities endured artillery bombardments that left many dwellings in ruins. North of the Potomac River, Confederate cavalry torched hundreds of structures in Chambersburg, Pa., on July 30, 1864. Harper’s Weekly published engravings of the destruction and reported that Chambersburg’s “burned district covers all the business portion of the town and some of the finest private residences.” Guerrilla depredations in every military theater took a toll on private as well as public buildings and other property, most notoriously when Confederates under William C. Quantrill sacked Lawrence, Kan., in August 1863.

A visitor to Fredericksburg, Va., in late 1864 captured the degree to which a protracted military presence transformed many areas. By that time, the Army of the Potomac and the Army of Northern Virginia had waged four huge battles within a few miles of Fredericksburg, and many smaller actions and periods of Union occupation had further affected the local population and environment. The visitor noted that “few trees remain upon the hills…[and] not a fence nor an inhabited house….The rich plains bear no crops now but crops of luxuriant weeds….There are no hands at work in the fenceless fields—no signs of animated life about the deserted houses—.” Around Fredericksburg, he summed up, “All is still as death for miles and miles under the sweet and autumnal sun.” That person could not know that Fredericksburg, whose residents white and black were buffeted by the war, would not return to its 1860 population until 1900.