Ron Williams remembers his temporary duty assignment flying Douglas A-3B “Whales” from a carrier as the most challenging two years of his career

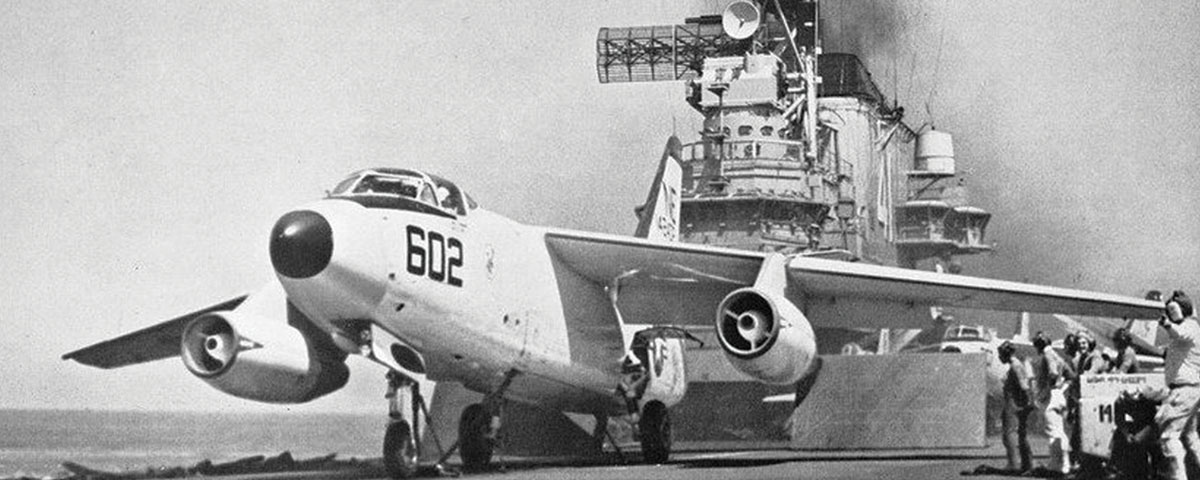

In 1964 U.S. Air Force fighter pilot Captain Ron Williams was selected for a prestigious two-year U.S. Navy exchange assignment with Heavy Attack Squadron 8 (VAH-8). He flew 110 combat missions in the Douglas A-3B Skywarrior, the heaviest and among the longest-serving aircraft to operate continuously from U.S. carriers. Nicknamed the “Whale” for its sheer size, the Skywarrior also earned another moniker among its three-man crews based on the difficulty of landing it on carriers, its lack of ejection seats and previous A3D designation: “All 3 Dead.”

Williams vividly recalls several harrowing missions during his assignment. In March 1965, while en route to Yankee Station off North Vietnam, he was in an A-3B being “hot refueled” with an engine idling on USS Midway, one of the smallest carriers in the fleet. A perfect landing in the Skywarrior brought the right wingtip to within just 40 feet of Midway’s island and three feet from parked aircraft.

“No way they’re going to launch us,” Williams confidently told his two-man crew. “Ceiling and visibility are hovering at minimums and it’s getting dark.” He admitted to feeling somewhat dismayed when Primary Flight Control commanded, “Launch the duty Whale to refuel.” (Among the Skywarrior’s many functions was serving as a refueling tanker.)

The loaded A-3B was catapulted from 0 to 150 knots in 217 feet, and entered the cloud cover at 100 feet. Visibility appeared to be less than a half-mile.

Reaching his assigned 5,000 feet, Williams was told the last jet had landed and instructed to immediately dump 30,000 pounds of fuel, keeping 5,000 pounds for a maximum 50,000-pound trap weight. Radar vectored his Whale onto final at 600 feet, then radioed, “You’re at a half mile—go ball.”

Williams looked up from his instruments. Nothing. Back on the gauges, he tried to hold the same heading and descent rate. At just 1/8th of a mile and 100 feet he finally saw the dim red “meatball.” It was perfectly lined up with the green datum lights and deck center, and he trapped on the no. 3 wire.

“I walked to our squadron ready room with weak, shaking legs and heart pumping 1,000 rpm,” he said. “Most of the pilots had watched my approach on the PLAT [Pilot Landing Aid Television] and were waiting for me.” Several of them grinned and one said, “Hey, Air Force, how’d you like night, no bingo, open-water carrier operations?” As a typical USAF fighter pilot, Williams calmly answered, “No sweat. Any chance the skipper could schedule us for a second launch?”

“I don’t know what I’d have done if he’d said, ‘Sure.’”

“I don’t remember too many of my thousands of landings on concrete,” Williams said, “but I remember every one of my 141 carrier traps.” His most memorable was on return from a solo night mission to drop a dozen 500-pounders on an enemy early-warning radar site northeast of Haiphong Harbor. Ceiling and visibility had dropped to minimums, and the sea was extremely rough, causing the carrier deck to rapidly pitch up and down. Experienced Douglas A-4 and McDonnell F-4 pilots were boltering: missing the carrier’s arresting cables and going around for another attempt.

“So, here I was, a fledgling USAF pilot flying his huge, ungainly Whale, hearing that my experienced USN buddies couldn’t get their little birds on board,” Williams commented.

Due to an inoperable air-to-air refueling system, his A-3B couldn’t be refueled. Bingo fuel was 4,500 pounds—enough to get to Da Nang with barely 1,000 pounds remaining. But, he noted, the Navy only used a USAF base as a last resort.

The air boss ordered him to descend from a fuel-conserving 25,000 feet to an uneconomical 1,000 feet and orbit 30 miles from the ship. When Williams radioed that he was bingo fuel and couldn’t refuel in flight, he received a “Roger” and instructions to come 10 miles closer.

With 2,000 pounds remaining, he transmitted, “If I can’t have an approach right now, then please launch the rescue helo and give me a bailout heading.” That finally got the air boss’ attention, but he cleared Williams to commence air refueling!

An uncomfortable Williams again reported that his plane couldn’t air refuel. This prompted a response of “Sorry. Cleared to CCA [Carrier Controlled Approach] frequency.”

As Williams rolled inbound, he took a last look at the fuel gauge, and wished he hadn’t. It showed less than 1,000 pounds—enough for only one approach. Midway was pitching so badly the meatball was moving quickly from full-scale low to high.

Inside a half-mile, the deck started drastically down. To get back on glide path without building airspeed, Williams did a big no-no: He pulled the twin J57 throttles to idle. Spool-up to full power would take an impossible 18 seconds.

“I felt sure the ship would act like always and wallow around in the bottom of the swell long enough to land,” Williams recalled. “The only other option was to hope we had enough fuel to get high enough to bail out.”

He pulled the yoke back in an effort to arrest his rate of descent, which only magnified it. “It looked like I was going to plant 23 tons of aluminum and the three of us in the ‘spud locker,’” he said. “The deck was rising fast as we hit, and I do mean hit, the deck short of the no. 4 wire, and probably with 9 or more Gs. The impact knocked all three of us unconscious. Two things saved us: first, the A-3B’s strength; second was my idle rpm allowed the airspeed to decrease so much that there wasn’t the energy to bounce the tailhook over the wires.”

When Williams regained consciousness, a glance at the fuel gauge showed it flickering a hair above 0 pounds. “Such a landing normally would have been most severely graded by the LSO [landing signal officer],” he noted. “However, when LSO Stu Corey entered our ready room, all he did was give me a big hug!”

When Williams left Midway, he said, “I was certified as a Centurion with a minimum of 100 arrested A-3B landings on one carrier—and I was a half-inch shorter.” He would go on to earn his colonel’s eagles in the Air Force Reserve, and later retired from TWA as a 747 captain with 28,000 hours in his logbook.

This article originally appeared in the September 2017 issue of Aviation History. Subscribe here!