A landmark study gave African Americans credit for being important actors in their freedom quest

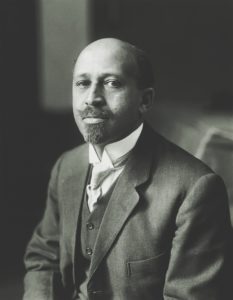

Black Reconstruction: An Essay Toward a History of the Part Which Black Folk Played in the Attempt to Reconstruct Democracy in America, 1860-1880 appeared on New York publisher Harcourt, Brace & Company’s list of new titles in 1935. Written by W. E. Burghardt Du Bois (1868-1963), a leading African American intellectual, sociologist, and historian best known for The Souls of Black Folk: Essays and Sketches (1903), the book received a good deal of attention from newspapers but less from mainline academic journals. Du Bois challenged the prevailing interpretation of Reconstruction as a dark time when carpetbaggers, scalawags, and their recently freed Black allies ran roughshod over a prostrate White South struggling to recover from the Civil War. That interpretation, widely disseminated by D. W. Griffith’s blockbuster film The Birth of a Nation (1915) and by Claude G. Bowers’ best-selling The Tragic Era: The Revolution After Lincoln (1929), shaped scholarly and popular attitudes toward Reconstruction for many decades. In a major departure from previous—as well as much subsequent—literature, Du Bois treated enslaved people during the war and freedpeople in its aftermath as important actors, rather than as passive pawns in the political, military, and economic struggles of the era. In doing so, he anticipated scholarship from revisionist studies by Kenneth M. Stampp and others in the 1960s, to the landmark work of Eric Foner in the 1980s, and down to the present. Anyone familiar with Henry Louis Gates’ Reconstruction: America After the Civil War, first aired on PBS stations in 2019, would find many similarities between that documentary and Du Bois’ 750-page masterwork.

Apart from its detailed examination of Reconstruction, Du Bois’ book offers a great deal to students of the Civil War. It presents a powerful argument for what later came to be called the concept of self-emancipation, whereby African American actions on the ground in the Confederacy forced politicians in Washington to proceed more quickly to end slavery. Du Bois relied on a Marxist-inspired economic analysis that cast the enslaved population as workers who rose up against the aristocratic class in the Confederacy. He sought to explain “How the Civil War meant emancipation and how the black worker won the war by a general strike which transformed his labor from the Confederate planter to the Northern invader, in whose army lines workers began to be organized as a new labor force.” The point regarding Black contributions to Union victory, while overstated, is clear and compelling—as African American refugees flocked to Union positions, they deprived the Confederacy of their labor, worked and eventually served as soldiers for the United States, and by their efforts contributed significantly to suppressing the Southern rebellion.

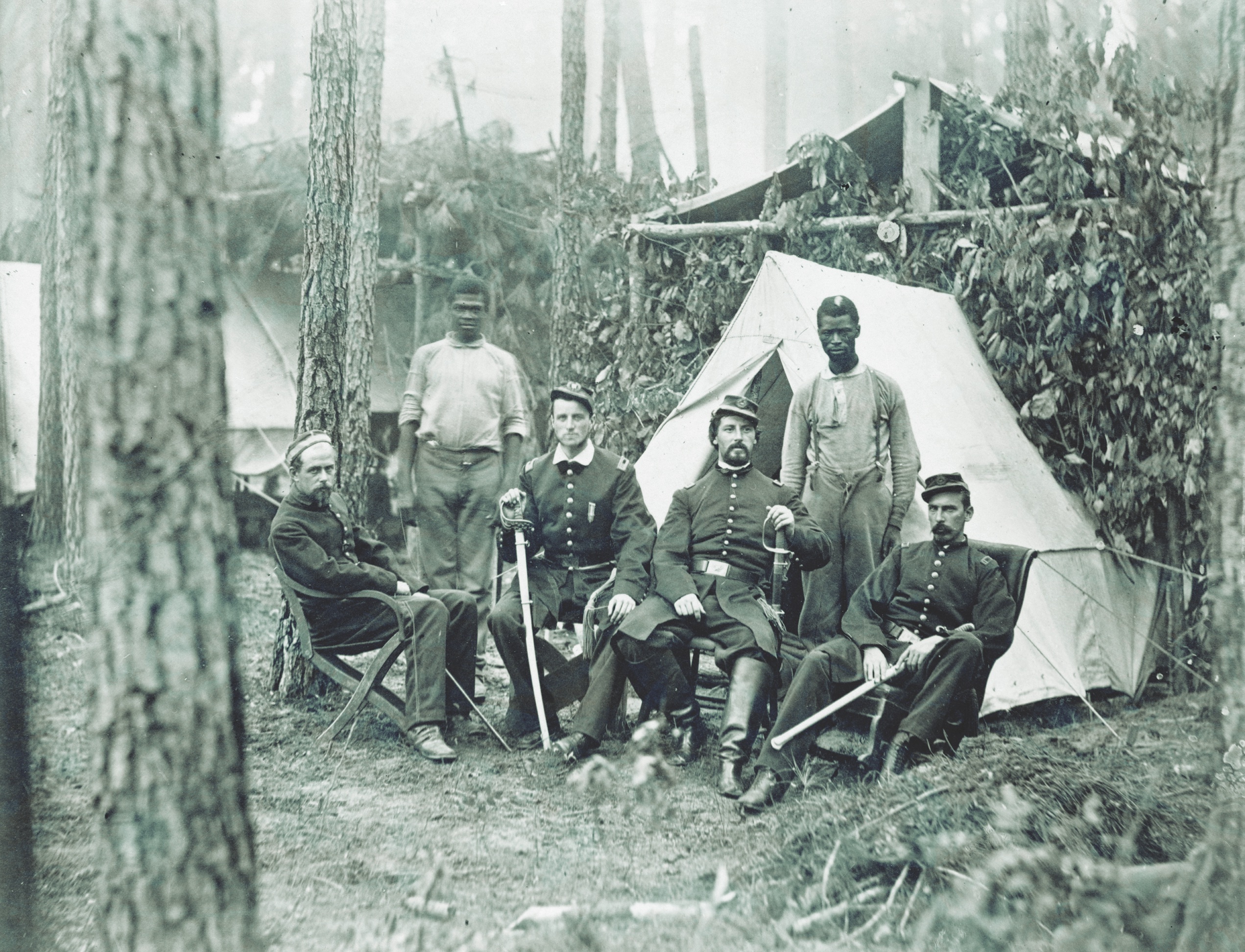

Du Bois correctly linked an enslaved workforce directly to the Confederate war effort. “The South counted on Negroes as laborers to raise food and money crops for civilians and for the army,” he noted, “and even in a crisis, to be used for military purposes.” With nearly 4 million enslaved people available to keep the economy running, the Confederacy could mobilize a huge percentage of its military-age White males. But as the war progressed, African Americans, through steady movement to Union lines and work slowdowns on plantations and farms, engaged in what Du Bois termed “The General Strike” that eroded the Confederacy’s capacity to mount an effective military resistance. Overall, the “guns at Sumter, the marching armies, the fugitive slaves, the fugitives as ‘contrabands,’ spies, servants and laborers,” Du Bois observed, furthered the process of emancipation and marked the progress of “the Negro as soldier, as citizen, as voter…from 1861 to 1868.”

Black Reconstruction handles the role of U.S. military forces in ending slavery very well. It sets the stage by identifying the overarching war aim for most of the loyal population. “The North did not propose to attack property” at the outset, Du Bois asserted: “It did not propose to free slaves. This was to be a white man’s war to preserve the Union, and the Union must be preserved.” “Freedom for slaves furnished no such slogan,” continued Du Bois, who estimated that not “one-tenth of the Northern white population would have fought for any such purpose.” Yet when Federal forces “entered the South they became armies of emancipation.” Wherever they marched, regardless of soldiers’ racial attitudes, the armies weakened Confederate control over enslaved people.

The arrival of blue-clad soldiers swelled the number of African American refugees. In turn, Union planners who oversaw the war effort “faced the fact, after severe fighting, that Negroes seemed a valuable asset as laborers, and they therefore declared them ‘contraband of war.’ It was but a step from that to attract and induce Negro labor to help Northern armies”—and after 1863 to enroll thousands of Black soldiers.

The impact of armies, not the efforts of the small number of abolitionists in the loyal states, settled the issue of slavery. “Freedom for the slave,” Du Bois insisted, “was the logical result of a crazy attempt to wage war in the midst of four million black slaves, and trying the while sublimely to ignore the interests of those slaves in the outcome of the fighting.”

By fleeing to Federal camps across the Confederacy, African American refugees “showed to doubting Northerners the easy possibility of using them” to subjugate the Rebels. “So in blood and servile war,” judged Du Bois, “freedom came to America.”

After Appomattox, the same attitude that sustained the Union as the preeminent focus of the loyal White citizenry undercut the possibility of achieving true racial equality. The postwar tragedy lay in the fact that “the Reconstruction of the Southern states, from slavery to free labor, and from aristocracy to industrial democracy,…[was not] conceived as a major national program of America, whose accomplishment at any price was well worth the effort ….” Had the nation made that effort, Du Bois concluded at a time when Jim Crow reigned supreme across much of the United States, “we should be living today in a different world.”