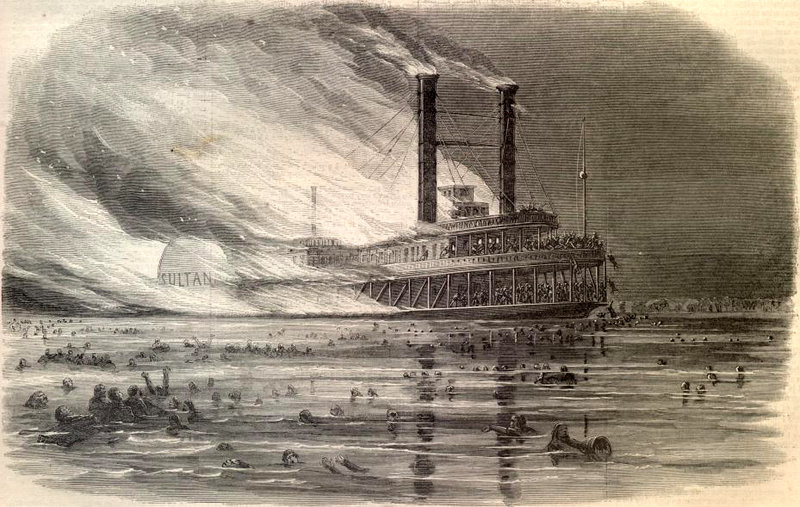

‘I could see fire and hear groans and screams and seemen jumping in the river by the hundreds . . . . ’

William French Dixon—20 years old—was farming in Henderson County, Kentucky, when Lincoln’s call for volunteers in 1861 sent him back to his native state of Indiana to enlist in the 25th Indiana Volunteers. He was joined in Union service by his 60- year-old father and two brothers. Wounded at Fort Donelson in February 1862, Dixon was sent home on leave. When he recovered, he was commissioned a second lieutenant in Company A, 10th Indiana Cavalry, in late 1863. It was while serving with this unit that he was captured at Hollowtree Gap on December 17, 1864, during the Nashville campaign, and sent to Andersonville Prison. Dixon endured the horrors of the prison camp for four months before being paroled at war’s end. He thought his troubles were over when he reached Union-held Vicksburg, but he was wrong. He was put aboard the troopship Sultana. Dixon’s memoirs furnish this eyewitness account of the explosion of the steamer Sultana during the night of April 26-27, 1865.

On April 25, 1865, the ill-fated Sultana landed at Vicksburg. There were over two thousand prisoners of war crowded on board her. She pulled out from Vicksburg for Camp Chase. In a short time we had lost sight of Vicksburg and were gliding along at a merry rate, the boat making her usual stops up the river. We were all talking of home and friends and the many good things we would have to eat. We consoled ourselves that we had lived through it all and now were in the land of the free. We had no thought but that we would be at home in a few days feasting with our loved ones once more….Night passed and morning came. Some time in the forenoon was reached Helena [Ark.] where we stopped for a short time. While here a photograph was taken of the boat with her mass of prisoners aboard. After leaving Helena we steamed on up the river to Memphis. At Memphis the boat unloaded some freight and took on a supply of coal. Night soon came on and I gave those sick comrades their supper and bid them goodnight for the last time. Very soon we were all sound asleep and dreaming of home. It was past midnight and while the boat proceeded on her way up the river about two o’clock, ten miles above Memphis her boilers exploded and over seventeen hundred lives were lost in less time than it takes to tell it. [The official investigation said 1,238; other reliable estimates go as high as 1,647]. I was lying on the crowded cabin floor near the ladies cabin and the floor did not blow up quite as far back as where I was sleeping. I was sound asleep and knew nothing until I was awakened by a sudden jar that threw me across the boat…and I heard someone calling out that the boilers had blown up and that the boat was on fire, and now the thought rushed through my mind…of the long months that I had struggled for existence in prison, of the friends at home waiting to receive me, and now that I must die an awful death. The river being so high, the water so cold, the night so dark and the boat now on fire…I did not have the slightest idea that a single soul would get out alive to tell the story…the fire was under headway and I saw that I must make a choice of one or two things…to either burn to death or drown. As I preferred the latter I began to make preparations with the resolution…to improve any and every opportunity that might present itself for my safety. All was now confusion on the boat. I could see fire and hear groans and screams and see men jumping in the river by hundreds, hanging together in clusters and going under, for ever so many of the poor crippled and scalded comrades would drag themselves to the side of the boat and drooping in the cold water disappear from sight, many were fastened in the debris of the boat, and soon perished in the flames….I secured two small strips of plank, and watching a chance to jump in as near to where I stood as possible, when I went under and came up I had lost one of my strips of plank and that made my transportation very light. Turning my face from the dreadful scenes I began to look for shore…[but] could see nothing but darkness…I could hear men holloring [sic] and crying in every direction….They would strangle and that was the last of them….There was quite a number that caught to the willows [on shore] and chilled to death, hanging fast to the limbs….I resolved to paddle along slowly, not to over do myself, for of course I did not know in what direction to go…I was getting very cold and numb, my mind was wandering and it seemed like everything was becoming blank….It seemed like a dream. It was getting light and there were two men pulling in another man at quite a distance and when they shifted their oars they made quite a noise, and it aroused me and I saw that I was passing by Memphis a distance of eleven miles and the bank was plain to be seen on the other side…and I just had strength to call and they came to my rescue….They took me back to Memphis, and at the wharf there were two boats lying side by side. One had a hot fire in the furnace and there was a comrade that helped me to the fire and threw an old coat around and gave me a glass tumbler half full of whiskey. I told them that was too much. They said it would not hurt me, so I drank it, and it was not long until I was hot inside and out. They took me over on the other boat where…they brought me…a pair of red flannel drawers….They had run out of clothing and they rushed me off to the hospital in this condition. I was very poorly for several days and could not stand on my legs. I spit blood from being injured in my chest and swallowing so much water, but after a few days treatment I got better and was, together with my other comrades, ordered on our way north. We were loaded on another steamboat and she caught fire and came near burning up. Finally the boat landed at Cairo, and we took the train to…Indianapolis where as the war was over we were mustered out and Johnny came marching home again.

We are grateful to Arthur J. Barter of Mt. Vernon, Ind., for allowing us to publish this memoir by his great uncle.

On a beautiful sunny Sunday morning, Amelia Gayle Gorgas, wife of Josiah Gorgas, chief of the Confederate Ordnance Department, walked into St. Paul’s Episcopal Church for the morning service. She sat with Judge John A. Campbell, former associate justice of the U.S. Supreme Court—then Confederate assistant secretary of war. She worshipped with Campbell that day because, as she phrased it, her own pew was filled with strangers. For four years she and her family had lived in Richmond while the Civil War closed in on the Confederate capital. But before the service closed that Sunday, April 2, 1865, the Confederate evacuation of the city would begin. Twenty-four hours later Federal troops would roam the streets. The fall of Richmond would be complete.

Thirty-five years after these events Amelia Gorgas wrote down her recollections for her children and grandchildren. At 74 in 1900, Mrs. Gorgas possessed a sharp memory. Her general recollections are corroborated by numerous official published accounts of the Confederate evacuation and the Federal occupation of Richmond. What is unusual about Mrs. Gorgas’ account is her graphic portrayal of Richmond life, life in a city disintegrating around her. Her story of this Southern disaster is poignant, a quality not found in the usual crisp accounts of the Confederacy’s death.

The daughter of Alabama Governor John Gayle and Sarah Haynesworth Gayle of South Carolina, Amelia was born in Greensboro, Ala. She was educated at Columbia Female Institute in Tennessee, and accompanied her father to Washington while he served in the U.S. Congress. There, the Gayles lodged in the same house as John C. Calhoun of South Carolina. Amelia and Calhoun developed a kind of May-and-December camaraderie, and she became his regular companion on sunrise walks. After her return to Alabama, she met and married a struggling young Army officer from Pennsylvania, Josiah Gorgas. Theirs was a genuine love match that lasted until death.

After their marriage, the pair embarked on the rootless odyssey of a military couple, repeatedly moving from one dreary, isolated Army post to another. Their sole respite was a brief assignment to Charleston, S.C., from 1858 to 1860.

Captain Gorgas then worked at the Frankford Arsenal in Pennsylvania through early 1861. To the surprise of many, on April 3 he tendered his resignation from the U.S. Army. Apparently, he loved the South as much as he loved his wife. A career ordnance officer, he offered his services to the Confederacy and was immediately placed at the head of the Southern army’s ordnance department with the rank of major.

Like so many other Civil War heroes, Josiah Gorgas’ most successful period in life came during the extraordinary crisis of wartime. Considered the administrative genius of the Confederacy, he provided sufficient weapons and ammunition to sustain the South for four years, rising to the rank of brigadier general. Meanwhile, his wife learned to fend for herself.

In April 1865, the couple’s six children (one only six months old) were left behind in Richmond while their father evacuated military equipment. The family would not be reunited to establish a household for a year, at which time Gorgas went into the iron-making business at Brierfield, between present-day Birmingham and Tuscaloosa in the wilderness of Alabama. After financial disaster there, in 1868 Gorgas became vice chancellor at the University of the South at Sewanee, Tenn. In 1878 he was offered the presidency of the University of Alabama. He served in that post only six months before being felled by a stroke. Thereafter, the university trustees made him librarian, a post increasingly assumed by Amelia and their now-grown daughters. After Josiah Gorgas’ 1883 death, Amelia continued working as a librarian until her retirement in 1907.

The episode at Richmond—although Amelia was unaware of it at the time— would be only the first of many crises in which she would have to take responsibility for herself as well as the children without Josiah’s help. She endured this harrowing ordeal by fire and survived it, as she would others in years to come. Here is her account:

Possibly it will be in place as “Historian” to give my experience of the evacuation of Richmond which after 35 years remains fresh in my memory. Sunday morning April 2nd ’65 while attending service in St. Paul’s church just as Mr. Minnigerode began his sermon a messenger swiftly and silently passed up the isle [sic] & whispered to Gen [Samuel] Cooper & other officers of the War Dept news which took them immediately from the church. The sermon proceeded & all was quiet until the messenger returned & going directly to the President’s pew gave the same whispered message. Mr. Davis arose pale but composed & with great dignity passed out of the church. In a moment it was known that Lee’s lines in front of Petersburg had been assaulted & broken by the enemy & could not be reestablished & Richmond must be evacuated by 8 o’clock that night. All was confusion & despair for every wife knew she must be separated from her husband & left to the mercy of a victorious army. The women were brave & aided to the best of their ability in the hurried departure of the men. I hastened to our quarters at the Armory & found preparations already begun to move the public property. My husband was too engrossed with his duties to assist me except to urge that I would leave the armory before the enemy entered the city as he knew the large public buildings would be used as barracks for the Federal soldiers. At 12 o’clock a messenger announced that the Ordnance train was ready & we parted not to meet again for many long and anxious months. That train was the last to pass over the bridge which was burned in an hour. Some men too old & infirm for military service & whom we had befriended assisted me in removing a few necessary things to my sister’s home on Cary St to which asylum my young children had already been taken. My oldest child a boy of 9 years remained at my side working all night—two faithful negro servants made Herculean efforts to leave nothing for the yankees & in their panic deposited on the top of Gamble Hill a sewing machine a mirror & a stand of shovel and poker & tongs. The latter are still preserved & used in my present sitting room. Just as the day was breaking a faithful sentinel rushed in & announced that the Yankees were coming over Church hill & begged me to leave at once as I could not save the furniture carpets &c &c. Taking my young son by the hand much exhausted by the night’s work we slowly made our way to Mrs. Bayne’s house through bursting shells & the lurid glare of many buildings on fire. Then began wild scenes of confusion on the street—liquor from the medical stores emptied in the gutters offered temptation to those who wanted to forget their fate. The contents of the open commissary stores were fought for by the poor wretches long strangers to food & clothing. As the sun rose long lines of the conquering army passed down our street. The brilliant uniforms of the officers & men & the sleek prancing horses formed a painful contrast to our ragged & shoeless braves & their half starved animals. We peered at the enemy through closed shutters even the children shrinking from the gaze of the terrible Yankees. My sister Mrs. Bayne & our friend Mr. James Alfred Jones both in delicate health were sitting together on a sofa in the sitting room when the fragment of a shell crashed through the window & passed within a few inches of their heads. My young son assisted me to spread wet blankets over the flat roof of the house to protect us from [sparks] & debris of the fires which at that time filled the air to suffocation. In the afternoon Willie rushed in & gave the alarm that Yankee soldiers were robbing our neighbor Mrs. Freeland of her silver plate & were coming next to our house. In hot haste my sister’s cook plunged her silver into a [container] of soft soap—my nurse & I threw the contents of my chest upon the top of an old fashioned shower bath the numerous pipes effectually concealing the silver. The mauraders [sic] were arrested before reaching our house but my silver bears honorable scars & dents of that dreadful evacuation day.

As night came on crowds of soldiers & negroes filled the streets & our fears increased as we had no male protector for the three women & nine children who composed our family. Learning that no guard would be granted unless by personal application my friend Mrs. Jones & I with courage born of despair determined to go to the head quarters of the Genl commanding Gen Ord & present a little note my husband had addressed to the Gen. asking protection for his helpless family. Gen Ord was a class mate of my Husbands at West Point. Dressed in deep mourning we drew on our crepe veils & with timid steps threaded our way through smoking ruins & masses of flaunting negro women & yankee soldiers to the city hall. The crowd around the enterance [sic] was so dense we could not have reached the Provost’s office but for the assistance of Dr. Nichols who had a way opened for us. Trembling we approached the man of authority, who proved not to be Gen. Ord. & presented our little note: he scanned us closely but politely & catching a glimpse of the pale & beautiful face of my friend invited us with some solicitude to be seated. In a few minutes, in response to instructions given to his orderly, a tall Prussian soldier presented himself & was ordered to follow the two ladies to their home & to protect them from molestation & intrusion. Our neighbors seeing us followed by an armed soldier concluded we were under arrest & sent messages of sympathy & encouragement. The guard was faithful & attentive & during the week he was on duty made warm friends of our children & promised next time he would “be a nice Confederate & not a bad Yankee” for which concession the little rebels warmly embraced him. After our little ones were asleep we three tired heartbroken women sat bewailing the terrible misfortune that had fallen our beloved city. We tried to comfort ourselves by saying in low tones, for we feared spies were in our servants, that the Capital was only moved to Danville & Gen [Robert E.] Lee would make a stand & repulse the daring enemy & we should win the battle & the day—alas, alas, for our hopes.

Originally published in the January 2006 issue of Civil War Times.