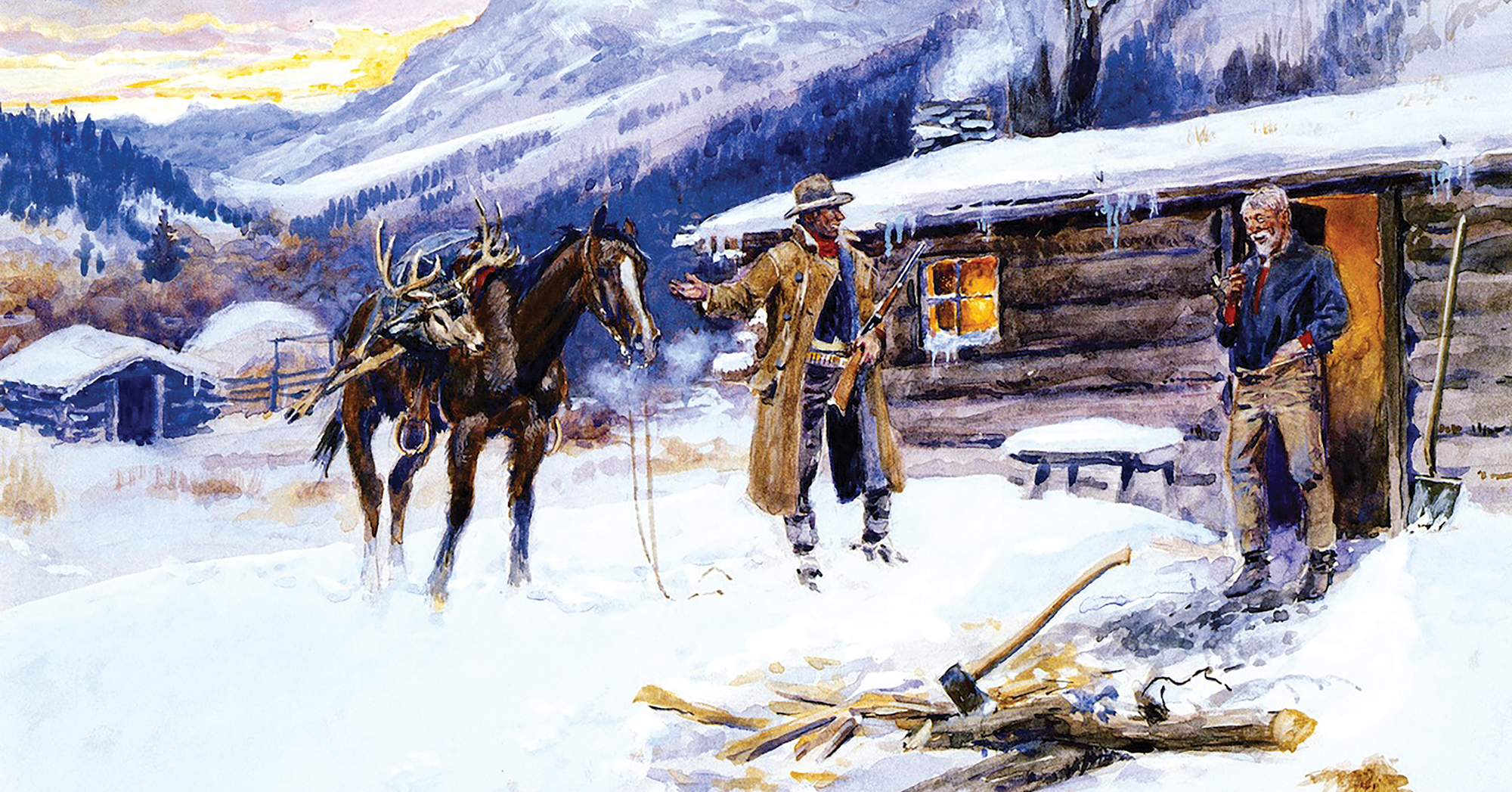

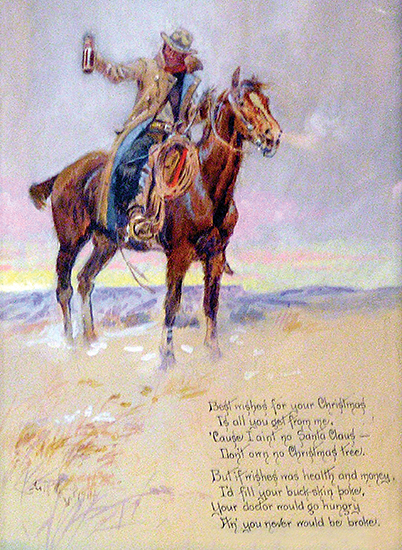

Death was often a close companion on the high plains of the 19th-century West. Christmastime could be an especially dangerous time for travelers, as storms unexpectedly blew down from the Rocky Mountains across the short grass prairies in deadly ground blizzards that blinded man and beast alike. Such was the case for a lone Nebraska cowboy sometime during the 1880s.

As the cold orange globe of the winter sun ascended over the rolling plains, a two-horse sleigh glided atop the snow on Christmas Day following a fierce blizzard the night before. A small family had left their home to visit ranching friends east of an unnamed town. Sighting an incongruous speck of color on the stark white prairie, the driver reined in the horses and halted the sleigh. Stepping down, he trudged through drifts to a gully in which he discovered the frozen corpses of a young Nebraska cowboy and his Appaloosa. Apparently, the young man had been heading east toward home. Tightly clasped in his frozen arms was a burlap sack containing a few Christmas packages, the bright tissue paper wrappings torn by the victorious wind. Lashed across the saddle horn atop the horse’s corpse was a miserable branch of a scrub pine tree.

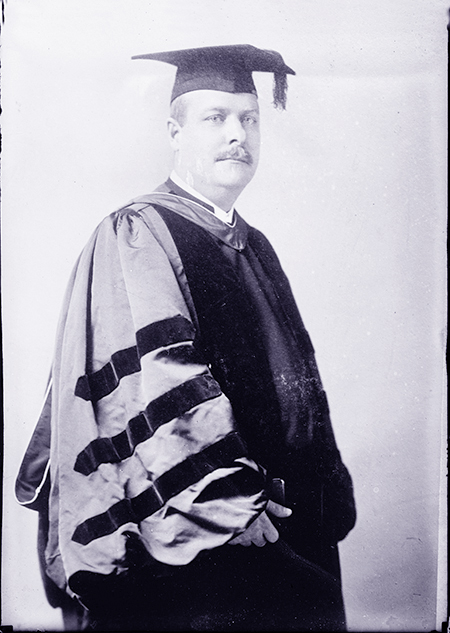

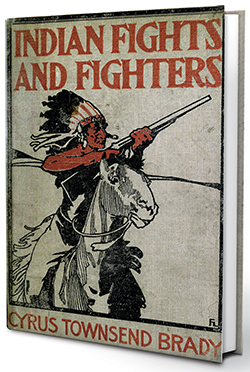

This melancholy tale is one of several Christmas stories written by prolific Western author the Rev. Cyrus Townsend Brady, an itinerant missionary on the high plains of Nebraska, Colorado and Kansas during the last two decades of the 19th century. Brady published more than 100 books on a score of subjects, but he is best known to Old West aficionados as the author of Indian Fights and Fighters, still in print. Brady is undoubtedly the writer who coined the famous ironic misquote of ill-fated U.S. Army Captain William J. Fetterman in 1866—“Give me 80 men, and I will ride through the Sioux nation”—published in Indian Fights and Fighters and in serial form in Pearson’s Magazine in 1904, four decades after Sioux, Cheyenne and Arapaho warriors wiped out Fetterman’s 80-man command outside Wyoming’s Fort Phil Kearny. Garrison commander Colonel Henry B. Carrington spent several months with the author, relating his often biased recollections of the Fetterman Fight (aka Fetterman Massacre).

Brady was born on Dec. 20, 1861, in Allegheny, Pa., the son of an affluent banker. From childhood he showed a strong interest in military history, as many of his later books reflect. He graduated from the U.S. Naval Academy in 1883, but for reasons unknown he left the service three years later. In the late 1880s he moved west with wife Clarissa to Omaha, where he worked on the Missouri Pacific and Union Pacific railroads.

While in Nebraska, Brady befriended several veterans of the Plains Indian wars, and he framed Indian Fights and Fighters around his interviews of their firsthand experiences. Soon after his arrival in Omaha he connected with an Episcopal church and began studying for the priesthood. Brady became a deacon in 1889 and a priest in 1890. That spring Clarissa died, leaving Cyrus a grief-stricken widower with three young children. He looked to the church for solace. In 1898 Brady returned to Philadelphia, where he met and married Mary Barrett, with whom he had three more children. He remained in the East till his death in 1920.

His time as an itinerant missionary had taken him on exhausting travels across the high plains grasslands, often at the height of dangerous winters. Those experiences made a lasting impression on him and informed his writing. His recollections of struggling young homesteader families at Christmastime became cherished subjects among readers of his articles in Pearson’s and the Ladies’ Home Journal. They also featured in several of his books. His best-selling 1900 book Recollections of a Missionary in the Great West presented several such Christmas stories. “I traveled over 91,000 miles by railroad, wagon and horseback,” he wrote, “preaching or delivering addresses upward of 11,000 times.” Other books incorporating Christmas tales included A Christmas When the West Was Young (1913) and A Baby of the Frontier (1915).

Brady embraced the literary device of nostalgia for the pathos of Western myth popular with readers at the turn of the 20th century. His sentimental stories are evocative, if not quite melodramatic, of his concept of the “pioneer spirit.” One poignant tale set in the 1860s relates the saga of young couple just trying to survive on the Nebraska grasslands. Two days before Christmas the family lost a small infant boy. “They buried him on Christmas Eve on the brow of the hill, looking over the ocean of open country,” Brady wrote. “They had clothed him in the simple dress she [his mother] had made for his Baptism, now grown quite too small for him. Of all the flowers, there was left in the house but a single rose, white; they laid that beneath the tiny hands.” Whether the episode was based on fact or is historical fiction is unknown, but the itinerant missionary author wrote with empathy and candor how the grieving mother questioned the existence of God that Christmas.

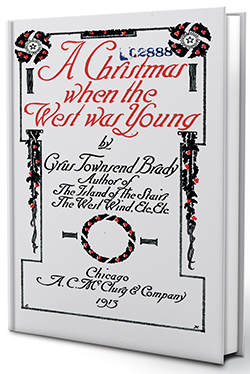

In 1913 Brady published the tale as “A Christmas When the West Was Young,” destined to become a best-selling children’s and young adult book

After burying their child, the husband had to make an unavoidable trip to the government land office in an unnamed town. Saddling his horse, he left his wife, vowing to return home on Christmas Day. Rousting the land office superintendent and freighting company agent from a saloon, he related his sad story and bought the necessary time to conduct his business. Halfway home the next morning the young homesteader happened on a smoldering Conestoga wagon in a rocky ravine. The horses, shot to death, lay dead in their traces. Scattered nearby were the bodies of three Indian warriors. Slumped over in the seat of the wagon was the body of a white woman. Her husband lay dying on ground, propped up against one of the wagon wheels. Before he succumbed, the man gasped to the young homesteader, “The—baby—!” In the bed of the wagon the young homesteader who had so recently lost his own son found an infant wrapped in a blanket and barely alive. As he stepped from the wagon, it burst into flames. He could not bury the parents in the rocky ravine, nor could he tote their bodies with him. So he did the next best thing. After searching in vain for any clue to their identities, he placed the bodies in the burning wagon for cremation. After cutting leather straps from the wagon harness, the man secured the bundled child and draped the straps around his neck in such a way he could hold the bundle tightly in his free hand. “Then he mounted his horse,” Brady wrote, “watched the flaming wagon for a moment or two, breathed a prayer and rode on.”

Soon an unearthly whiteness blocked the scant landmarks ahead, the air turned deathly cold, and the greatest blizzard he had experienced in his life broke around him. But on he plowed through the tempest, clinging to the precious bundle now enfolded inside his coat and inspired by the grieving wife who awaited his return. Through sheer intuition he tried to sense the way home, riding on until the horse could no longer carry its rider. Dismounting, the man grabbed the bridle and pushed ahead on foot toward a dim light just beyond the angry gray haze. He later had no recollection of stumbling through the doorway of a house with the horse in tow. It was his house. As his wailing wife revived him, he suddenly recalled. “The baby, there!” he shouted, pointing to the bundle on their bed. “It has no mother,” he told his wife, “and it is so hungry.” Brady wrote how her soul quivered and breast throbbed with mixed emotions. But then the baby boy opened its eyes—blue eyes, like those of her dead child. His hair was the same golden shade. “Her hands fumbled at the bosom of her dress, slowly at first, but finally with a passionate movement, she tore the remaining fastenings away, and even as He of the manger had done, the child drank.”

Brady ended his tale befitting the faith and moral compassion of his position as a Christian missionary:

The man watched her. He forgot his pain. He saw her eyes brim, he saw the tears sparkle, he saw them silently as a rain of mercy down her face. They could hear the scream of the wind outside. Within was peace and some of the joy of Christmas Day, for unto them had a child been given.

In 1913 Brady published the tale as A Christmas When the West Was Young, destined to become a best-selling children’s and young adult book.

“I did not get home until the day after Christmas,” Brady wrote. “But, after all, what a Christmas I had enjoyed!”

One Christmas morning, possibly in eastern Wyoming at the time of the great winters that destroyed the open range cattle empires, Brady hired a two-horse sleigh and started out in deep snow to deliver a requested sermon at a little brick church perched well out on the prairie. It was cold and drafty, so Brady performed the service in his buffalo overcoat, fur cap and gloves. Swirls of snow crept in through the window and doorframes to settle on the altar. Evergreens were absent, so members had decorated the sanctuary with sagebrush. “[The service] was short,” he recalled, “and the sermon was shorter.” Only a dozen people had braved the cold and snow to attend. After church the clergyman accepted a dinner invitation at a parishioner’s nearby farmhouse. The fare was meager. “There was no turkey, and they did not have even a chicken.” On the menu was ham, cornbread and a handful of potatoes. “There were two children in the family—a girl of 6 and a boy of 5,” he wrote. “They were glad enough to get the ham.” From the lunch his wife had packed, Brady produced a mince pie turnover, which he presented to the girl and boy. “Such a glistening of eyes and smacking of small lips you never saw!”

Brady’s heart went out to the children. After dinner he excused himself and returned to the church. Selecting the best of the wicker collection baskets, he decorated it with a ribbon borrowed from his emergency sewing kit. (“I am, like most ex sailors, something of a needleman myself,” he explained.) In the basket he placed the scissors, thimble, needles and thread, pincushion, buttons and other notions. He then hurried back to the house. “To the boy I gave my penknife,” Brady recalled, “which happened to be nearly new, and to the girl the church basket with the sewing things for a work basket. The joy of those children was one of the finest things I have ever witnessed,” he wrote. “The face of the little girl was positively filled with awe as she lifted from the basket, one by one, the pretty and useful articles…and when I added the small box of candy that my children had provided me, they looked at me with feelings of reverence, as a visible incarnation of Santa Claus. They were the cheapest and most effective Christmas presents it was ever my pleasure to bestow. I hope to be forgiven for putting the church furniture to such a secular use.”

Perhaps Brady’s favorite Christmas experience found him on a small spur run of a Western railroad. The two-car “plug” was running in the teeth of a Christmas Eve blizzard that brought the train to a standstill in a cut. The train comprised a smoker/baggage car and a coach. Sharing the coach with Brady were a drummer (traveling salesman), a cattleman, a ranch hand and a young widow with two small children. All were trying to get home for the holiday.

One of the crew immediately set out on foot for the nearest station to request an engine fitted with a plow, but it was obvious the train would remain stranded overnight. The downcast passengers gathered around an iron woodstove at the front of the car to commiserate. The men soon learned the widow had tried to make ends meet doing odd jobs but had given up and was returning home with her young ones to live with her mother. “The poor little threadbare children,” Brady wrote, “had cherished anticipations of a joyous Christmas with their grandmother. From their talk we could hear that a Christmas tree had been promised them and all sorts of things. They were intensely disappointed at the blockade. They cried and sobbed and would not be comforted.”

Tipping two seats sideways, the men stacked their overcoats to make beds for the little ones. They had reconvened around the stove when the drummer uttered, “Say, Parson, we’ve got to give those children some Christmas.” The others agreed. The cattleman produced a new pair of wool socks as stockings, but the men struggled to find appropriate gifts. “You all come along with me to the baggage car,” the drummer finally said. “So off we trooped,” Brady recalled. “He opened his trunks and spread before us such a glittering array of trash and trinkets as almost took our breath away.” The drummer told the others to pick out the best from the lot, and he’d donate them all. “No, you don’t,” said the cowboy. The others agreed, and the men happily paid the drummer for all the items they chose. They soon returned to the coach with “such a load of stuff as you ever saw before.” Two of them then trudged off onto the snow-blanketed prairie to find an acceptable stand-in for a Christmas tree, quickly returning with a large sagebrush. The widow decorated it with tissue paper from the drummer’s trunk, and the crew hung train lanterns around it. “Great goodness!” Brady remembered years later. “Those children never did have, and probably never will have, such a Christmas again. And to see the thin face of that mother flush with unusual color when we handed her one of those monstrous red plush albums which we had purchased jointly, and in which we had all written our names in lieu of our photographs, and between the leaves of which the cattleman had generously slipped a hundred-dollar bill, was worth being blockaded for a dozen Christmases. Her eyes filled with tears, and she fairly sobbed before us.”

After the children emptied their stockings, the Rev. Brady conducted a brief Christmas morning service. By early afternoon the crewman who had gone for help returned aboard the plow engine. More important, he brought with him a whole cooked turkey. “So the children had turkey, a Christmas tree and Santa Claus to their heart’s content,” Brady wrote. “I did not get home until the day after Christmas. But, after all, what a Christmas I had enjoyed!”

Brady’s affinity for the frontier Army certainly informed the descriptions of pioneers’ struggles he wove into his Christmas tales

The Rev. Brady recalled more than a few holiday seasons of great privation on the plains. One Christmas he helped unpack two wooden barrels filled with clothing and other necessities for destitute homesteaders at a little mission. A ladies’ aid society back East had packed and sent them. As Brady opened the second barrel, one little boy sniffling to himself in a corner remarked, “Ain’t there no real Chris’mus gif’s in there for us little fellers, too?” Recalling his own childhood Christmases when relatives plied him with nothing but clothing, Brady rooted through the second box “with a great longing, though but little hope. Heaven bless the woman who had packed that box, for in addition to the usual necessary articles, there were dolls, knives, books, games galore, so the small fry had some ‘real Chris’mus gif’s’ as well as the others.”

Snippets of other Christmases past appear in Brady’s writings. Some were sorrowful, as when he presided over funerals on Christmas Day. Some were more joyful, including abundant feasts at community celebrations. Others were mixed. Brady recalled one particular reception after a funeral. “The Christmas dinners were all late on account of the funeral,” he wrote, “but they were bountiful and good nevertheless, and I much enjoyed mine.”

To be certain, Brady was no proto-Hemmingway. Most of his books have long since disappeared from print, notably his scores of seafaring stories. Publishers have recently revived a few of his works, both nonfiction and fiction. Some produced by Leopold Classic Library and Wentworth Press appear in photocopy form online. But Indian Fights and Fighters has endured in print to the present with the University of Nebraska Press.

Brady was particularly enchanted with the Indian wars recollections of frontier Army veterans, though like most writers of his time he shied away from Indian reminiscences. As such, Indian Fights and Fighters is a strictly one-sided history of the conflicts. He tried to be fair to Indians and address their motives, but his lack of knowledge and intimacy with them is manifest in abbreviated accounts that by modern standards are somewhat condescending. Aside from passages in A Christmas When the West Was Young, his Christmas stories lack any Indians.

Brady’s affinity for the frontier Army certainly informed the descriptions of pioneers’ struggles he wove into his Christmas tales. After all, he firmly believed the Army had productively cleared the Great Plains, making it safe for settlement. Readers interested in learning more about the author’s mindset and frontier holiday traditions can still find his Christmas stories online and in print. Before his death in Yonkers, N.Y., from pneumonia at age 58 on Jan. 24, 1920, Brady wrote, “I trust that in thus striving to preserve the records of those stirring times I have done history and posterity a service.” Indeed, his surviving books remain a gift to succeeding generations.

Kansas native John Monnett has written many books and articles about the Indian wars. He relates Christmas stories from Cyrus Townsend Brady and many others in his 1999 book Rocky Mountain Christmas: Yuletide Stories of the West. For further reading Monnett recommends Brady’s 1904 book Indian Fights and Fighters and the 2017 edition of And Thus He Came: A Christmas Fantasy, first published in 1916.