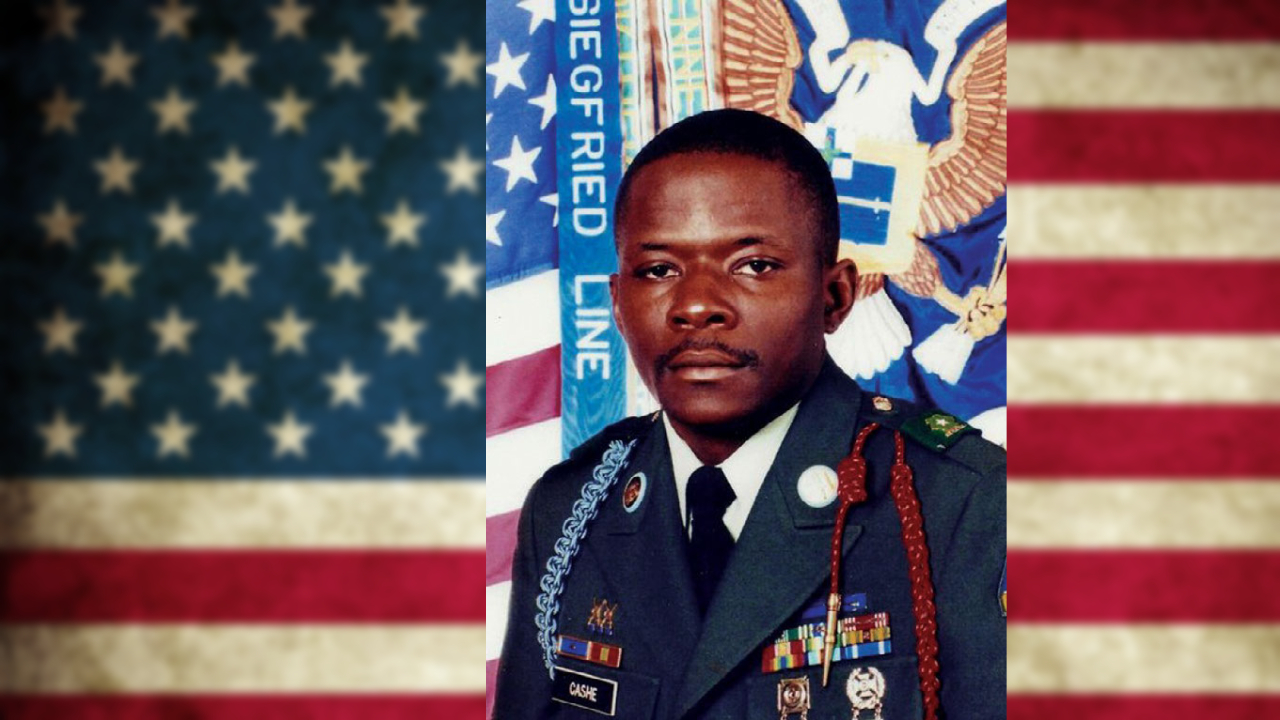

October 17, 2005, Samarra, Iraq: An IED exploded under a Bradley Fighting Vehicle designated Alpha 13, igniting its fuel cell, throwing fuel onto the uniforms and bodies of men inside. Sergeant 1st Class Alwyn “Al” Cashe from Sanford, Florida, was in the gunner’s hatch. Leader of the men in the Bradley, he managed to escape; then, while under enemy fire, he made three trips back into the burning BFV to pull six soldiers and an interpreter out. His own fuel-soaked uniform burned away, leaving only his helmet, body armor and boots. Covered with severe burns over as much as 90% of his body, he refused to be evacuated until all of his men had been medevaced. He died November 8, 2005, at San Antonio Military Hospital in Texas.

For his actions that day, Sergeant Cashe was awarded the Silver Star, the Army’s third-most prestigious medal. But Brigadier General Gary Brito, the commander who recommended him for the Silver Star, determined after further review that the sergeant should have been recommended for a Medal of Honor, America’s highest military award. Recipients of the Medal of Honor, always few and far between, have been almost non-existent in the War on Terror; critics say the criteria for awarding the medal reflect a World War II–mentality that needs to be adjusted to the realities of 21st-century asymmetrical warfare. An extensive review by Military Times found 10 veterans of Iraq and Afghanistan who received lesser awards, but when records of their deeds are compared with those of earlier Medal of Honor recipients, it would appear they should have been honored with the highest award; SPC Alwyn Cashe is one of the ten.

His story motivated a Cold War–era veteran named Harry Conner to begin a campaign to raise public awareness of Cashe’s selfless heroism and aid Brigadier General Brito’s efforts to have the sergeant’s Silver Star upgraded to a Medal of Honor. On December 11, 2014, HistoryNet spoke with Conner.

HistoryNet: You’re a veteran yourself, aren’t you? When did you serve?

Harry Conner: I was in the U.S. Army, 1972-80. I started out in the 101st Airborne but when I went to Germany I was with the Third Infantry. I was in the 1/10 artillery, but I was liaison NCO with 1/15th, which was the unit Al later served in. Later I was a drill sergeant before leaving the military.

I retired at the end of last March to just work on promoting his story. His resting place in Sanford, Florida, (near Orlando)is about 10 miles from where I’m living right now. I started from his resting place when I made the two bike rides I’ve done to publicize his story.

HN: There have been several news stories over the last few years about the paucity of Medal of Honor recipients in our 21st century wars. What was it about Alwyn Cashe’s story that motivated you to get involved?

Harry Conner: I was drinking coffee at a store one Saturday when I picked up the Orlando Sentinel and saw an article about his actions and the effort to have him awarded the Medal of Honor. He was in the Third Infantry and had been a drill sergeant, so there was a connection. I was technically retired, so I went home that same day and contacted Darryl Owens, who had written the piece in the Sentinel. He gave my contact information to Al’s sister Kasinal Cashe White; she contacted me, and I’ve been working on it ever since. It was probably the next Saturday that I talked to General Brito, and I went to see Congresswoman Sandi Adams with Al’s sister Bernadine in the winter of 2011–2012.

The first problem was that it had been more than two years since Sergeant Cashe’s actions occurred. The Army has a two-year time limit on recommendations for awards. Getting a waiver requires Congressional approval, so we had a sort of chicken-or-the-egg situation: the Army said it couldn’t consider awarding him the Medal of Honor because it is past the time limit and they would need Congressional approval to waive that limit. Congressional representatives said they would approve the waiver if the Army decided to award him the medal.

Congressional representatives John Mica and Corrine Brown have said they will support waiving the two-year limit, however, so the time limit is no longer an issue.

HN: What have been some of the questions the Army has related to this case?

Harry Conner: The criteria for awarding the Medal of Honor hasn’t changed since World War II. It’s based on engaging the forces of a hostile nation; it doesn’t always reflect the situations of the War on Terror. One of the stumbling points was small arms fire. Part of the existing criteria is that the person “engaged in a hostile action with an enemy force of the United States.” Was the IED remotely detonated or pressure-detonated when the Bradley rolled over it? Was there small-arms fire? Those are some of the questions.

There was small-arms fire. Alpha 12, the Bradley behind the one Al was in, did return fire on the insurgents; its men dismounted and engaged the insurgents. Somewhere between 10 and 15 insurgents were taken prisoner and turned over to higher HQ. I don’t know what happened to them after that.

When the typical citizen thinks of Medal of Honor recipients, he thinks of a soldier out there mowing the enemy down. I don’t think Al even had his weapon with hem when he got out of the Bradley. All he cared about was saving his men. But he exceeded any reasonable expectation of what he had to do that day.

HN: What have you been doing to call attention to this case?

Harry Conner: Last April—the 28th, I think—I started out on a bicycle ride of 1,204 miles from Al’s resting place to the 9/11 Memorial in New York. Later I rode 554 miles from his resting place to Fort Benning, then to Fort Stewart, home of the 3rd Infantry Division. (Both locations are in Georgia; Fort Benning is where infantry are trained to drive and maneuver Bradley vehicles like the one Sergeant Cashe was in at the time of the incident.)

Harry Conner: Last April—the 28th, I think—I started out on a bicycle ride of 1,204 miles from Al’s resting place to the 9/11 Memorial in New York. Later I rode 554 miles from his resting place to Fort Benning, then to Fort Stewart, home of the 3rd Infantry Division. (Both locations are in Georgia; Fort Benning is where infantry are trained to drive and maneuver Bradley vehicles like the one Sergeant Cashe was in at the time of the incident.)

The bicycle rides were not about me—they were intended to get publicity for telling Sergeant Cashe’s story, and they have. The real work behind the effort to have him awarded the Medal of Honor is being done by Brigadier General Gary Brito. This goes through same military examination process as other awards do, but the process is even more demanding when the Medal of Honor is involved. It is our nation’s highest military honor; you could say, in a way, that it is “sacred.”

General Brito has the testimony of witnesses. He has Al’s medical report from the hospital where he died. He has all the paperwork necessary. In fact, he just filed the final report last Monday (December 8, 2014) with the Army Awards branch, unless the Army comes back to him with additional questions. The Army can decide to do one of three things: Sergeant Cashe retains his Silver Star with no recommendation to upgrade that award; it can be upgraded to the Distinguished Service Cross (the Army’s second-highest award); or his medal can be upgraded to the Medal of Honor.

HN: Tell us a bit about your Facebook page devoted to Alwyn Cashe.

Harry Conner: We’re up to 4,800 members now, I think. Our group is very, very, very narrowly focused. We exist for two reasons. First, we will do whatever we can to support the efforts of General Brito in securing the Medal of Honor for Alwyn Cashe. Second, we want to educate the public about what Sergeant Cashe did on October 17, 2005. The farther we get from 9/11, and with the war in Afghanistan winding down, the less people will understand or appreciate the War on Terror or the people like Sergeant Cashe and the sacrifices they made.

I don’t allow socializing or jokes on the site. I tell new members we’re here to achieve the awarding of the Medal of Honor, so we treat our group with the respect the Medal of Honor deserves.

To some degree we have to educate our own members. One thing I’ve had to monitor is people who want to send letters to their members of Congress or start petitions. Congress has nothing to do with the medal beyond waiving the two-year time limit. The process is handled through the military chain of command. People will frequently refer to the Congressional Medal of Honor, but it is simply the Medal of Honor.

HN: So what can people do?

Harry Conner: The best way to help out our group is to just urge friends and family to join the group and continue to spread the story of Sergeant Cashe and what he did, to try to get the public to understand what he did, why he did it, and to understand the fact we have men and women in our armed services doing this (risking themselves) for our country every day.

HN: Is there anything else you’d like to add in closing?

Harry Conner: I’d like you to think about something. Imagine burning your hand in a hot oven or on a grill, how bad it would hurt. Al caught on fire three times. Only his boots, helmet and body armor were left on him. The amount of time he had to be on fire for all of his outer gear to burn off is just unimaginable. General William Webster—Al’s division commander and one of the people recommending the Medal of Honor for him—says when you see you are on fire, normal human instinct would be to put it out and stay the hell away from the fire.

Al was in the gunner’s hatch when the IED went off. He freed himself, then he and Sergeant Daniel Connelly got (Specialist) Darren Howe out of the vehicle and on the ground and put out the fire on him. Cashe told Connelly to stay with Howe when he saw the vehicle was on fire, while Al went back to Alpha 13. That’s when he ignited.

He went inside Alpha 13 three times, pulling out his men and an interpreter who died on the scene. Their own rounds were cooking off in the vehicle before he finished. Alpha 12’s guys had dismounted and were returning fire on the insurgents. Sergeant Cashe was just sort of stumbling around; when he reignited, Joel Garcia had to tackle him and put out the fire. Help arrived from Forward Operating Base McKenzie, about four kilometers away. They set up an aid station in a ditch, but a dust storm prevented helicopters from medevacing the men; they had to be taken to FOB McKenzie by vehicle. Al refused help until everyone else had been carried to medevac, then he refused to be carried. With some help, he walked to the medevac flight. We need to tell the story of this man and why he deserves the Medal of Honor.

Click here to read the steps required for awarding the Medal of Honor.

Click here to see an example of the Medal of Honor recommendation form.