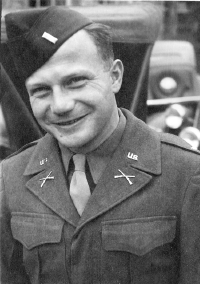

In the middle of April 1945, First Lieutenant Fritz Schnaittacher, an intelligence officer with the U.S. Seventh Army in Germany, was guarding a German POW. The man begged to be released so he could return to his wife in the nearby village of Forth. “Who is your wife?” Schnaittacher demanded. “Gunta Haas,” the prisoner told him. “Oh yes, Gunta Haas,” Schnaittacher said. “She lives in house number 35, and if you look across the street there is house number 52, and the Protestant minister’s house is on the left, and the firehouse is on the right.” Flabbergasted, the prisoner exclaimed, “If American intelligence has all this information, how can we win the war?” What the POW didn’t know was that Forth was Schnaittacher’s hometown. Schnaittacher, a German-born Jew, had fled his country in 1933 after nearly being imprisoned in the newly constructed concentration camp at Dachau. He joined the U.S. Army in 1942 and was assigned to intelligence because of his fluency in German. On May 1, 1945, he was at the gates of Dachau. Soon after, he sent the following letter to his wife Dorothy in Brooklyn:

In the middle of April 1945, First Lieutenant Fritz Schnaittacher, an intelligence officer with the U.S. Seventh Army in Germany, was guarding a German POW. The man begged to be released so he could return to his wife in the nearby village of Forth. “Who is your wife?” Schnaittacher demanded. “Gunta Haas,” the prisoner told him. “Oh yes, Gunta Haas,” Schnaittacher said. “She lives in house number 35, and if you look across the street there is house number 52, and the Protestant minister’s house is on the left, and the firehouse is on the right.” Flabbergasted, the prisoner exclaimed, “If American intelligence has all this information, how can we win the war?” What the POW didn’t know was that Forth was Schnaittacher’s hometown. Schnaittacher, a German-born Jew, had fled his country in 1933 after nearly being imprisoned in the newly constructed concentration camp at Dachau. He joined the U.S. Army in 1942 and was assigned to intelligence because of his fluency in German. On May 1, 1945, he was at the gates of Dachau. Soon after, he sent the following letter to his wife Dorothy in Brooklyn:

My dearest Dottylein,

Twelve years ago to day I came to Munich—yesterday we took it—to day we were in the heart of it—another coincidence. The past few days were some of the greatest and saddest in my life. Our regiment took Dachau or should I say liberated the human wreckage which was left there. This I consider one of the most glorious pages in the history of our regiment, not because the fighting was tough, it wasn’t, but because it finally opened the gates of one of the world’s most hellish places.

Twelve years ago I missed it by the skin of my teeth. This time I saw it—I shall never forget it, and nobody will, who has seen it. You know that I had never doubted the truth of all the atrocities, of which we have been reading—I know they could never be exaggerated, but at the same time I could never visualize this insane cruelty until I was confronted with it now, and now I cannot comprehend it, and it almost seems more unbelievable than before I had seen the victims of Nazi German culture.

You have heard the stories over the radio—I don’t want to add much more—the most striking picture I saw was the “death train”—I say picture, no not picture, but carload and carload full of corpses, once upon a time people, who were alive, who were happy and people who had convictions or were Jews—then slowly but methodically they were killed. Death has an ugly face on these people—they were starved to death—the positions they were lying in show that they succumbed slowly—they made one move, fell, were too weak to make another move, and there are hundreds of such lifeless skeletons covered by some skin. I tried to find out the origin of this train. Some of the stories corresponded—whether this train was to leave Dachau or had just arrived is not essential—essential is that they were locked into these cattle cars without sanitation and without food. The SS had to take off in a hurry—we came too fast—it was too late to cover up their atrocities.

Yet there were even worse scenes at Dachau than the one I tried to describe. And still Dachau was considered only a drop in the bucket in the eyes of an experienced observer, or high ranking SS officer. He had been in a hospital in camp as a convalescent. I was called in as an interpreter, and first when I met him I was unaware of his identity, but expected him to be a political prisoner who was anxious to help us in the elimination of those who were guilty for all these crimes. I greeted him accordingly. Then I found out he was an SS officer—my hand, which had shaken his, felt as if it wanted to shrivel up. I told him so too. Then he made the following statement, take it for what it’s worth “Yes I am an SS officer, not because I wanted to, but because I had to—still I am proud to have been an SS officer, only as such I was able to see the true face of Hitler and his system, and only as such I was able to help the unfortunate ones a tiny bit.” Then he told us about the Concentration Camp near Katowicz—Dachau is just child’s play in comparison to Katowicz.

Dottylein I hate to close this letter so abruptly — this is all dark, but there are some light aspects in all of this nightmare too—they will follow shortly.

I love you my Dottylein with all my heart and soul.

Your Fritz

One of the light aspects was having the end of the war in sight. On May 8, 1945, the day the German surrender took effect, Schnaittacher wrote to his wife, “It is a beautiful day, as if nature wanted to contribute its share to the glamour of peace. It’s warm, everything is blooming, butterflies are fluttering over flowers, birds are singing — it would be so nice if you my Dottylein and I could plant ourselves on the shore of this swift river, side by side, and enjoy the peace, enjoy the sun, the fresh air, or dream together about our personal future — it would be so nice—it will be actually, not just hope, not just longing. May it be soon.” Fritz Schnaittacher passed away in 2007, on his 94th birthday.

Andrew Carroll has donated his War Letters Legacy Project to Chapman University (online at www.chapman.edu/research/institutes-and-centers/cawl/index.aspxletters.com), dedicated to preserving and collecting correspondence from all of America’s wars. If you have a World War II letter you would like to share, please send a copy (not originals) to:

Attn: Andrew Harman

Archivist

Center for American War Letters Archives

Leatherby Libraries

Chapman University

One University Dr.

Orange, CA 92866