For the masked vigilantes of Virginia City, Nevada, the wheels of justice ground too slowly.

Shortly after midnight on March 14, 1871, Hugh Kelly and Charley Fletcher were strolling down B Street when they spied something ominous—reflected orange light flickering off the houses opposite Piper’s Opera House. Springing into action, the pair filled buckets with water from a nearby trough, forced their way into the opera house and doused the fire before it could spread.

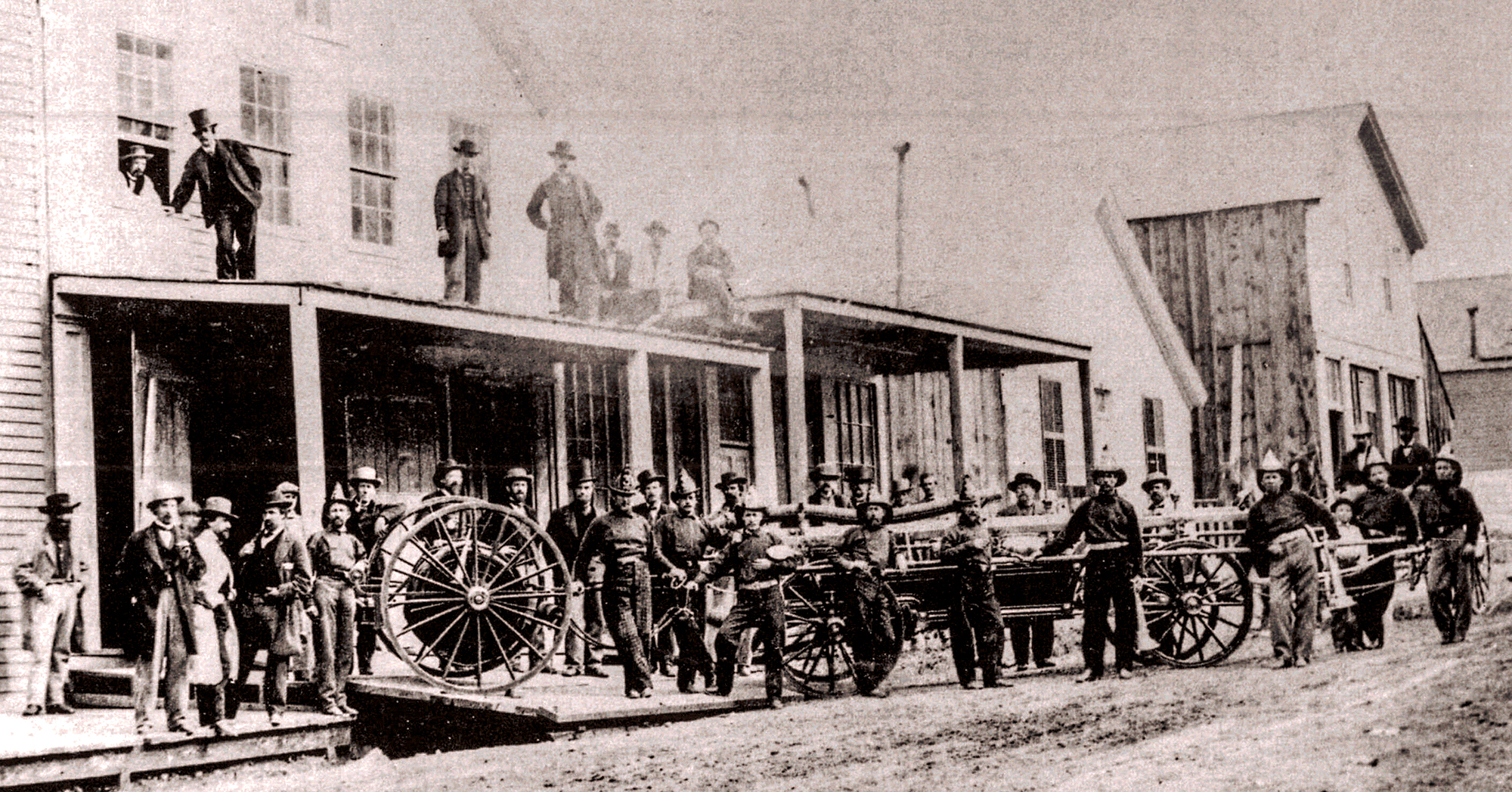

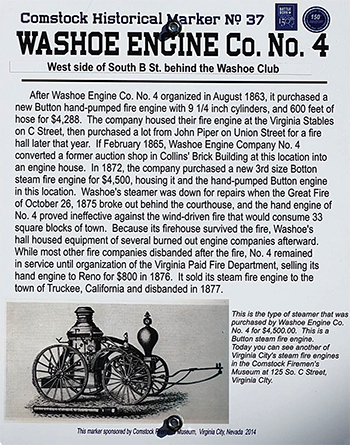

Police Chief George Downey moved just as swiftly. Within a half hour, on the corner of C and Union streets, Downey arrested William Willis for arson. His grounds for suspicion were strong. Hours earlier Willis—ironically, a volunteer firefighter of Washoe Engine Co. No. 4—had bulled his way into the opera house to watch that evening’s play. After proprietor John Piper ordered him out, Willis had sworn he’d “get even.” Later that night Officers George Potter and William Stout spotted Willis lurking about the opera house and went to investigate but soon lost sight of him. On hearing about the fire, the officers reported to Downey, who soon located Willis. Coal oil on the latter’s hands and coat sleeves was evidence enough to warrant his arrest.

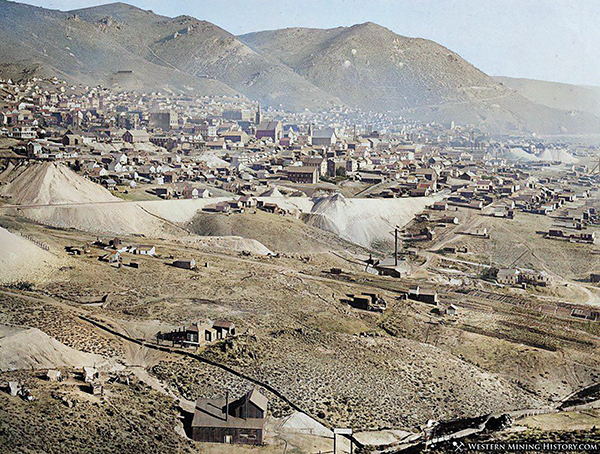

Willis was in bigger trouble than that, for the opera house fire was only the latest of several blazes that had ravaged the Nevada boomtown that year. The other fires had killed four people and reduced dozens of homes and businesses to ashes, damages running into the hundreds of thousands of dollars. “Arson” was on everyone’s lips, and on February 18 the Nevada State Journal had fanned the flames. “It seems to be well established that there is an organized gang of incendiaries in Virginia City,” the paper surmised, “and that the numerous fires in that city were kindled by the gang. What object these miscreants expect to accomplish by destroying the city is not clear; but there is a determination on the part of the respectable citizens to wreak summary vengeance upon anyone caught at the nefarious work.”

With Willis in custody, townsfolk wondered what other fires he might have set and whether he’d acted alone. If he were tried and convicted, they reasoned, he could potentially be induced to name his fellow arsonists on a promise of reduced jail time. But for the 601—Virginia City’s vigilance committee—that wasn’t good enough by half.

Tossing one end of their rope over a charred beam, they fixed the noose around their quarry’s neck and gave it a tug

Willis had been behind bars for less than 24 hours when a knock came at the jailhouse door. From inside Jailer Benjamin L. Higbee called out, “Who is it?”

“A friend,” came the reply.

Pushing back the bolt, Higbee cautiously opened the door. All at once a masked man burst through the gap, seized the jailer by the throat and pushed him inside. On the intruder’s heels followed a dozen others armed with shotguns and pistols, their faces disguised by masks fashioned from red or white cloth cut with crude eyeholes. Retrieving the jailer’s keys, they opened the cell holding Willis and spirited him out of jail.

The vigilantes marched Willis to the scene of the crime—the basement of Piper’s Opera House. Tossing one end of their rope over a charred beam, they fixed the noose around their quarry’s neck and gave it a tug. With his life on the line, Willis confessed to having set the fire. He also implicated three fellow incendiaries. Helping him set the opera house fire was Charley McWilliams, whom Willis claimed had also burned down a cabin near the old provost station in the lower part of town. Tom Laswell, Willis said, had set ablaze a boardwalk outside the Collins House hotel. The lead firebug, however, was 24-year-old hothead Arthur Perkins. According to Willis, Perkins had helped Laswell commit arson, incinerated Athletic Hall, set the fire next to the confectionary store on C Street and destroyed the Invincible Hose Co. engine house. Plunder, Willis claimed, had been the object of Perkins’ devilish design.

Having forfeited any bargaining power, Willis was perhaps surprised when the vigilantes removed the noose and returned him to jail. On the strength of his confession authorities soon arrested McWilliams and Laswell. Perkins, however, was already in jail on a charge of murder.

Murder was one thing. Arson and murder was quite another. The 601 decided on a more permanent solution for Perkins.

Born in the fall of 1846 aboard Thomas H. Perkins, a U.S. Army transport en route from New York City to Rio de Janeiro, the newborn boy was christened Arthur Perkins Heffernan—his first name after the ship’s captain and his middle name after the ship. From Rio Perkins continued around Cape Horn to San Francisco. Soon after arrival the boy’s father, Corporal Charles Heffernan, was mustered out, moved the family to Tuolumne County and opened a store in Jamestown. After amassing a small fortune, Charles pivoted to politics as an essayist and Democratic Party delegate. When of age, rebellious young Arthur moved 100 miles northeast to Virginia City, where he dropped his surname and took to calling himself Arthur Perkins.

Like Willis, McWilliams and other venturesome young men, Perkins joined Washoe Engine Co. No. 4. He also became embroiled in a local war over water rights at Seven-Mile Canyon. “He was a fine-looking man,” prospector Dwight Bartlett wrote of Perkins in a letter to his mother, “but he had fight on the brain.” On March 5, 1871, for seemingly no reason, he shot and killed young English prospector Bill Smith in the International Saloon. Perkins was soon arrested, and by the time of Willis’ confession at the end of a rope the murder suspect was securely locked up in the Storey County Jail. Sharing a cell with him was Moses Remington, who days earlier had shot his wife in the face in a fit of jealous rage.

The two cellmates were about to receive uninvited guests.

Secrecy was paramount. Any alarm might thwart their plans. One shotgun-wielding vigilante snuck into the engine house of Young America Engine Co. No. 2, on South C Street, and roused the slumbering Sam Wyckenham. In a subsequent interview with the local Territorial Enterprise Wyckenham claimed the vigilante asked whether he was the steward. When Wyckenham replied that he was, the masked man told him, “Well, if you are the steward, take this pistol and go up into the belfry, and if anybody comes to ring the bell on any pretense whatever, you shoot him. Get up there, quick!” Under the gaze of the shotgun-wielding vigilante, Wyckenham took the proffered pistol, donned his coat and climbed to the belfry. “He kept poor Sam there in the cold and storm for about an hour and a half,” the Enterprise wrote, “when he was permitted to come down, and the masked man, taking the pistol from him, left.”

Meanwhile, around 1 a.m. the main body of vigilantes, some 80 strong, reached the sheriff’s office, several dozen of them cordoning off the surrounding streets. Men on their way home who came upon the sentinels were flatly told, “Go back!” A group of printers coming off the night shift at the newspaper ran into the cordon. The foreman, plainly terrified, thought the masked men were robbers and cried out he didn’t have a cent. Recognizing the printers and recalling they lived just within the line, a handful of the vigilantes escorted them home.

“Will I be quite safe here?” the foreman asked from his open doorway.

“You are safe enough inside,” one of the masked men replied, “but if you step a foot out of the house, we will blow the top of your head off.” The foreman shut the door.

Inside the county jail Sheriff Thomas A. Atkinson and Undersheriff Phil Stoner woke to knocking. As Sheriff Atkinson slid back the bolt, a dozen masked men forced the door and rushed inside. All carried guns, which they leveled at the officers. One held up a feeble candle. After dragging Undersheriff Stoner from bed, they demanded the keys to Perkins’ cell. The officers stoutly refused, even after suffering abuse at the vigilantes’ hands, Atkinson receiving a black eye for his troubles. Over the next few minutes the mob thoroughly ransacked the room, one of the men finally turning up the keys, pigeonholed in a corner desk.

Hearing the commotion from his cell, Perkins realized he was the target. “They have come for me,” he told Remington. “I may as well say goodbye. This is my last night on earth.” Moments later vigilantes appeared at the cell door.

“Come out,” one said as the key turned in the lock. “We want you.”

Hurriedly dressing, Perkins protested his innocence. Although he did not deny shooting Smith, he claimed “it was an accident.” He categorically denied any role in arson, particularly the torching of the Invincible Hose Co. engine house. Perkins swore he’d been playing billiards in the Washoe Exchange at the time. His protestations meant nothing to the vigilantes. They had already judged Perkins guilty; their role was to execute the sentence.

When Perkins, in his excitement, fumbled with his boots, he was told to forget them. “Where you are going,” one vigilante sneered, “you will not need boots.”

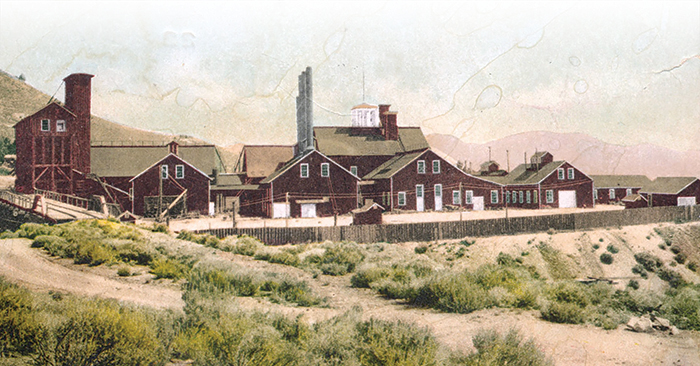

By then a crowd of curious spectators had gathered out front on B Street between Union and Taylor, hoping to catch sight of Perkins as the mob emerged from the jail. The vigilantes instead hustled him out the back. Following A Street to Sutton Avenue, they marched Perkins up to the Ophir Mine, whose treasures had started the 1859 rush to the Comstock Lode.

A small outbuilding sat atop one of the Ophir shafts. From the front of the building, 12 feet off the ground, jutted a beam. Around it the vigilantes looped their rope. The doomed man was then made to stand on a plank spanning an ore car path some 6 feet deep. One man adjusted the noose around Perkins’ neck while others bound his hands and feet and blindfolded him with a towel.

Citing anonymous sources, the Enterprise reported Perkins seemed collected at the end, mentioning his relatives. As his executioners yanked away the plank, Perkins jumped. The jump may have altered his fall, for his neck did not snap. Instead, he strangled to death, legs thrashing and arms straining against his bonds. After making certain he was dead, the vigilantes pinned a calling card to the left lapel of his coat: Arthur Perkins—Committee No. 601.

Authorities made little effort to identify the vigilantes. Rumors quietly swirled that opera house owner Piper, the former mayor of Virginia City, might have had good reason to string up Willis. Others might have questioned firehouse steward Wyckenham’s story—that an armed vigilante gave him a pistol and “forced” him to guard the alarm bell, seemingly unconcerned Wyckenham might turn the gun on him. Some also likely wondered how hard jailer Higbee had resisted the vigilantes who’d assaulted him, or why he thought opening the front door to a stranger in the dead of night was a smart play.

Mostly, however, people were glad Perkins was no longer a threat, dismissing his assertion he’d killed Smith by accident. “He killed a man in cold blood,” Bartlett wrote to his mother. Further down in the letter Barrett captured the spirit of what the average citizen was feeling:

Virginia [City] is overrun with bad characters of every description.…Do you wonder that the people took the law into their own hands? Four lives have been lost in these fires within a few months. Since Virginia was settled, 168 men have been killed, and only one man has been hung by law, and only five or six punished at all. It is impossible to get a jury to convict a man for killing another unless he does it in cold blood.

Whatever the case, the Enterprise reported that hundreds of people attended Perkins’ funeral. Perhaps members of the 601 wanted one last look at the arsonist whose life they had extinguished.

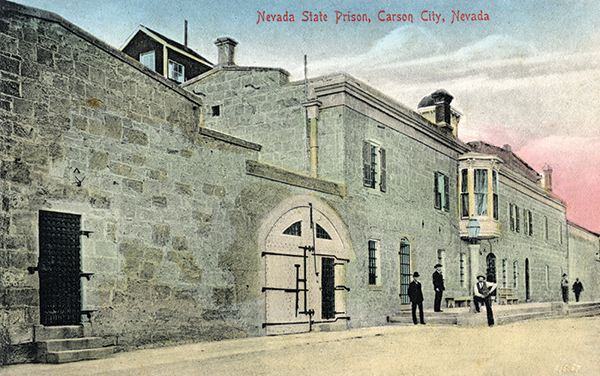

Willis, who had fingered the dead man for his role in the Virginia City fires, was soon brought to trial, convicted and sentenced that April to 21 years in the Nevada State Prison at Carson City. On September 17 he and 28 others escaped (see sidebar above). Willis didn’t get far. Ten days later a posse led by Sheriff Atkinson and Chief Downey captured him and fellow escapee John Squires in Seven-Mile Canyon, returning them to prison. Despite the time added to his sentence, Willis received a pardon and was released in 1879. WW

Matthew Bernstein teaches literature at Matrix for Success Academy and Los Angeles City College. For further reading he recommends Watchmen, by Alan Moore and Dave Gibbons, and the Dwight Bartlett Letters at the Huntington Library in San Marino, Calif. This article was published in the October 2020 issue of Wild West.