Union and Confederate Seamen and Marines Embraced a Photographic Phenomenon

Ronald S. Coddington is the editor and publisher of Military Images magazine. His latest book, Faces of the Civil War Navies: An Album of Union and Confederate Sailors, is the fourth in a continuing series. He is a former contributor to The New York Times Disunion blog and Civil War News.

[dropcap]1[/dropcap] These photographs weren’t in my history books and I find them fresh, and new, and compelling.

They’re also intimate. Soldiers’ and sailors’ portraits were never intended for consumption in a larger way. These were for families or for friends, or for comrades, and those images stayed with the families; but by the time of the Civil War centennial in the 1960s, these images were finding their way to the marketplace. I think it was because the memories had faded and the family connections were lost. Also, before the Civil War, there were no images of common soldiers. Most individuals who posed for oil portraits were generals or folks who had the means to do so. Private soldiers were relegated to being part of the background in an engraving or painting of a battle and the faces were created by the artist. But with the advent of photography, you’re beginning to see the soldier or sailor as an individual.

[dropcap]2[/dropcap] You call the carte de visite photo format the social media of the Civil War. Why?

Previous to the carte de visite you had tintypes, ambrotypes, and daguerrotypes. They were not easily copied, but instead onetime pieces of art. When the carte de visite gets to America from Europe on the eve of the Civil War, you suddenly had a reproducible, inexpensive format. A person could buy a dozen for $1.50 or $2 and share them with family, friends, and comrades. That spreads around information about individuals, and in my mind, that’s what goes on in social media.

People were mesmerized by these images in the 1860s. Cardomania is an actual word that people used to describe this fad, which some people loved and others hated. The photo album is born from the carte de visite. People needed a way to display the ones they collected. Many soldiers and sailors had photo albums of the comrades in their company or of shipmates.

In the beginning the carte de visite appealed more to individuals somewhat higher on the socioeconomic scale. There was an idea that it was for the upper crust, but as the war went on and the advantages of the format became apparent, the carte de visite became popular with a wider demographic, including junior officers and enlisted men.

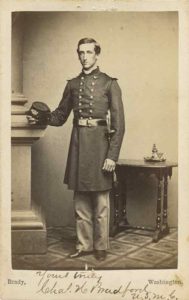

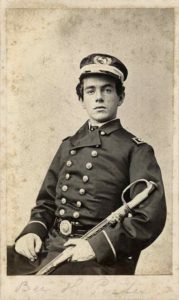

[dropcap]3[/dropcap] A couple of the sailors you include in your book took part in land battles, such as Lieutenant Benjamin Horton Porter.

Porter was a fascinating young man. At 17, he was ordered to duty from the Naval Academy, and he wanted so badly to be in the thick of the fighting that when Federals assaulted Roanoke Island, N.C., on February 7, 1862, he and a crew of seamen were placed in charge of a battery of howitzers. As soldiers advanced, Porter and his sailors pulled the guns along the ground with ropes to keep in line with the infantry. He got a lot of attention for that deed, including being given a ceremonial sword that he’s holding in his picture. He died at age 20 on January 15, 1865, in the Second Battle of Fort Fisher, an amphibious assault by soldiers and a contingent of sailors. His unit never made it off the beach.

[dropcap]4[/dropcap] A number of your subjects participated in Farragut’s epic Mobile Bay attack in August 1864.

Mobile Bay is as close to a major battle on the scale of a Gettysburg that the navies had, so you have all these little dramas playing themselves out as the fighting went on. Because the battle was so celebrated on the Union side, many sailors wrote down their accounts during and after the war. But the truth is, whether a sailor was at Fort Fisher, Hampton Roads, Norfolk, New Orleans, or Charleston, every one has a story I tried to capture.

[dropcap]5[/dropcap] What do the faces of Civil War soldiers and sailors say to us today?

I think it’s important to understand what individuals did when the nation was in crisis. When you find out what they did, in large ways and small, it speaks to us across the generations and it informs us about what our responsibilities are as citizens. We have the responsibility to think about what concepts like “liberty” and “democracy” mean and how we are to defend them.