The Battle of Gettysburg raged over three horrible days, July 1, 2, and 3, 1863, and turned an agricultural crossroads town into an international byword for titanic conflict. The fighting that took place on the hills, ridges, and farm fields of Gettysburg, did not, however, occur as a result of random chance. Events unfolded as they did because of a series of critical decisions made before, during, and after the engagement by commanders in both armies and at all levels. A select number of these decisions determined the way that the battle, and the entire campaign, unfolded.

Gettysburg was shaped by 20 such critical decisions. One was strategic, three operational, 14 tactical, and two organizational. Eight were made at army, six at corps, three at division, and three at brigade levels. Eight were made by Union commanders, 12 by Confederate commanders. All were implemented by the thousands of soldiers in the Army of Northern Virginia and the Army of the Potomac.

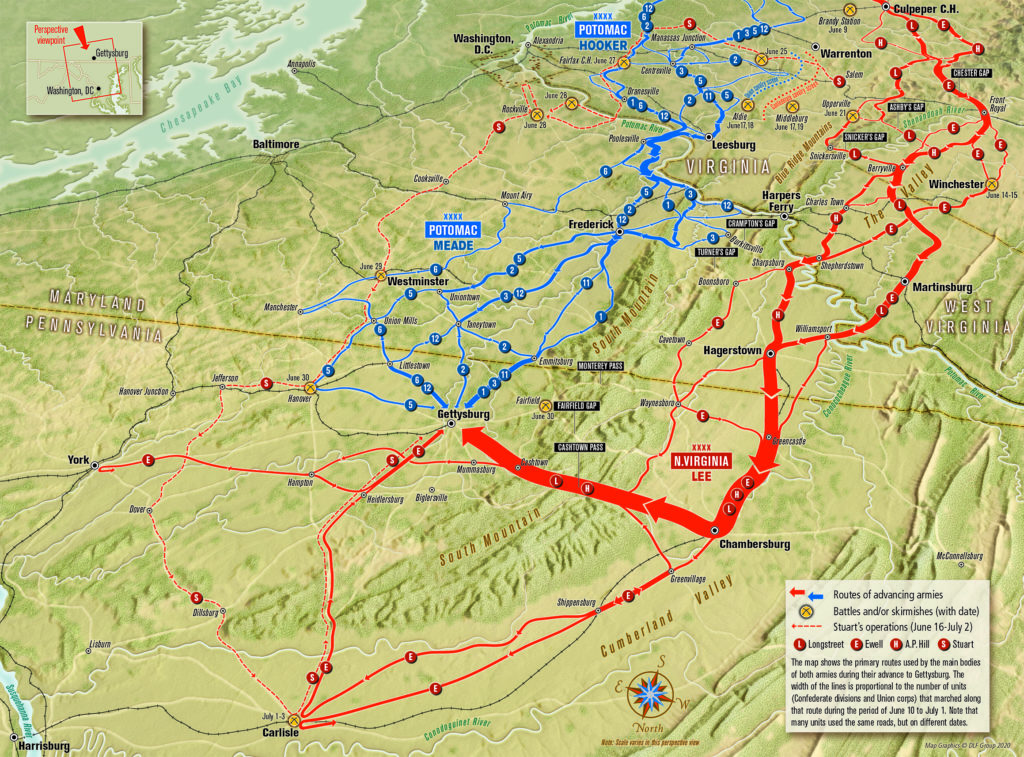

1. The Army of Northern Virginia Goes North — Army Level Strategic Decision

Despite Confederate victory at Chancellorsville in early May, both armies still faced each other across the Rappahannock River, just as they had after the Battle of Fredericksburg some four months previously. General Robert E. Lee had various campaign options for the summer of 1863. Two kept the Army of Northern Virginia in its namesake state. One called for his army to join the fighting in the Western Theater. A fourth option sent his army across the Potomac River into Northern territory—allowing it to gather forage and supplies, disrupt Union campaign plans and perhaps gain a political advantage with a battlefield victory. The Battle of Gettysburg resulted from Lee’s decision to go with that option.

Despite Confederate victory at Chancellorsville in early May, both armies still faced each other across the Rappahannock River, just as they had after the Battle of Fredericksburg some four months previously. General Robert E. Lee had various campaign options for the summer of 1863. Two kept the Army of Northern Virginia in its namesake state. One called for his army to join the fighting in the Western Theater. A fourth option sent his army across the Potomac River into Northern territory—allowing it to gather forage and supplies, disrupt Union campaign plans and perhaps gain a political advantage with a battlefield victory. The Battle of Gettysburg resulted from Lee’s decision to go with that option.

2. The Army of Northern Virginia Reorganizes — Army Level Organizational Decision

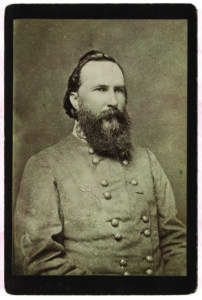

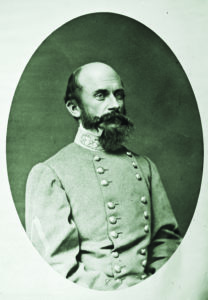

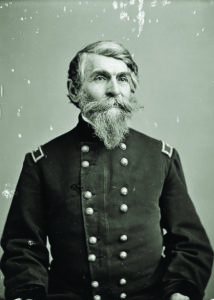

Since the summer of 1862, Lee’s army had been organized into what were known first as wings, then corps, commanded by Lt. Gens. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson and James Longstreet, left. Lee believed the two-corps arrangement was too large for effective control, especially in wooded terrain. Jackson’s mortal Chancellorsville wound, Lee reorganized his army into three infantry corps under Longstreet and Lt. Gens. Richard S. Ewell, below, and Ambrose P. Hill. The army’s reserve artillery was disbanded and its batteries reassigned to the infantry corps. This provided each corps with five artillery battalions, and the flexibility of assigning battalions to the infantry divisions or keeping them under corps command. The cavalry organization remained basically as it had been.

Since the summer of 1862, Lee’s army had been organized into what were known first as wings, then corps, commanded by Lt. Gens. Thomas J. “Stonewall” Jackson and James Longstreet, left. Lee believed the two-corps arrangement was too large for effective control, especially in wooded terrain. Jackson’s mortal Chancellorsville wound, Lee reorganized his army into three infantry corps under Longstreet and Lt. Gens. Richard S. Ewell, below, and Ambrose P. Hill. The army’s reserve artillery was disbanded and its batteries reassigned to the infantry corps. This provided each corps with five artillery battalions, and the flexibility of assigning battalions to the infantry divisions or keeping them under corps command. The cavalry organization remained basically as it had been.

The reorganization gave Lee greater flexibility in maneuvering and deploying, but left him with a large number of inexperienced commanders: two of three corps commanders, four of nine division commanders, and nine of 39 brigade commanders.

3. Reorganization of the Artillery of the Army of the Potomac —Army-Level Organizational Decision

The Army of the Potomac began the war with a decentralized and inefficient artillery organization. There was an army artillery reserve, but it was reduced after the Seven Days Battles in June–July 1862, and further decentralized after Antietam. The decision was made to reorganize the army’s artillery again after its inefficient deployment at the Battles of Fredericksburg and Chancellorsville.

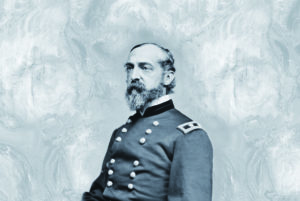

There were two options for the reorganization: Assign all of the army’s artillery to corps level or designate some batteries to corps level and use others to create a large Artillery Reserve. The latter option was chosen, and 69 batteries were organized into 14 artillery brigades, or battalions. Each infantry corps was assigned an artillery brigade, and its commander reported directly to the corps commander. Two artillery brigades were assigned to the cavalry corps. Brigadier General Robert O. Tyler commanded the five artillery brigades of the Artillery Reserve, and he was responsible to the army’s chief of artillery, Brig. Gen. Henry J. Hunt, below. Hunt reported to army commander, Maj. Gen. Joseph Hooker, and after he was relieved on June 28, Maj. Gen. George G. Meade.

The artillery’s reorganization eliminated many command and supply problems, and provided a flexible organization that could distribute artillery batteries across a wide front or could concentrate them for massed fire on a specific target. On all three days at Gettysburg, the new Federal artillery organization decisively helped blunt Confederate assaults.

4. The Confederate Cavalry Goes Astray — Division-Level Operational Decision

Army of Northern Virginia cavalry commander Maj. Gen. J.E.B. Stuart excelled at providing intelligence, protecting the army’s flanks, and raiding. On June 23, 1863, Lee granted Stuart permission to ride around the Union army if he met no hindrance, cross the Potomac River, and screen the right of Ewell’s Corps as it marched north. Stuart began his movement on June 25, but encountered the Union 2nd Corps near Haymarket, Va., preventing him from moving north. Rather than turn back, he decided to continue. But after running into more Union troops near Fairfax Court House, he had to move farther to the east, and was not able to turn north until he reached Rowser’s Ford on the Potomac River. The gray troopers would actually be east of the Union army, unable to screen Ewell’s right.

Stuart took his three best cavalry brigades away from his army, and left his two remaining cavalry brigades without strong leadership. Lee was without effective reconnaissance, and the Confederate general was surprised when he encountered the Army of the Potomac in Pennsylvania.

5. Buford Conducts a Delaying Action — Division Level Operational Decision

Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry division was assigned the duty of conducting reconnaissance for the Army of the Potomac’s left and left-front, and his troopers arrived at Gettysburg on June 30. That afternoon and evening, Buford, right, received sufficient information to believe that Confederate forces were west and north of Gettysburg. Buford sent this intelligence to 1st Corps commander Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, near Emmitsburg, Md., and to Cavalry Corps commander Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton. Buford had several options. He could deploy his cavalry on the key terrain west of Gettysburg, on the high ground south and southeast of town, or fall back to the vicinity of Emmitsburg.

Brig. Gen. John Buford’s cavalry division was assigned the duty of conducting reconnaissance for the Army of the Potomac’s left and left-front, and his troopers arrived at Gettysburg on June 30. That afternoon and evening, Buford, right, received sufficient information to believe that Confederate forces were west and north of Gettysburg. Buford sent this intelligence to 1st Corps commander Maj. Gen. John F. Reynolds, near Emmitsburg, Md., and to Cavalry Corps commander Maj. Gen. Alfred Pleasonton. Buford had several options. He could deploy his cavalry on the key terrain west of Gettysburg, on the high ground south and southeast of town, or fall back to the vicinity of Emmitsburg.

Buford chose to establish positions on the terrain west of Gettysburg, intending to delay the Confederate advance for as long as possible while Union infantry reinforcements rushed to the crossroads town. This decision would influence both armies’ positions and maneuvering for the next three days.

Buford chose to establish positions on the terrain west of Gettysburg, intending to delay the Confederate advance for as long as possible while Union infantry reinforcements rushed to the crossroads town. This decision would influence both armies’ positions and maneuvering for the next three days.

6. Reynolds Reinforces Buford — Corps-Level Tactical Decision

This decision has a symbiotic relationship with Buford’s. Reynolds commanded the 1st Corps and, as a wing commander, also had operational control of the 11th and 3rd Corps. When Buford informed him of Confederates marching toward Gettysburg, Reynolds had three options: Deploy into a defensive position near Emmitsburg, occupy the high ground south and southeast of Gettysburg, or occupy the ridges west of the town.

Reynolds, right, decided to place his own corps on the march and ordered the other two corps to Gettysburg. The 1st Corps arrived in time to take over the fight from Buford and hold Confederate forces west of Gettysburg until late afternoon.

7. Rodes Attacks — Division-Level Tactical Decision

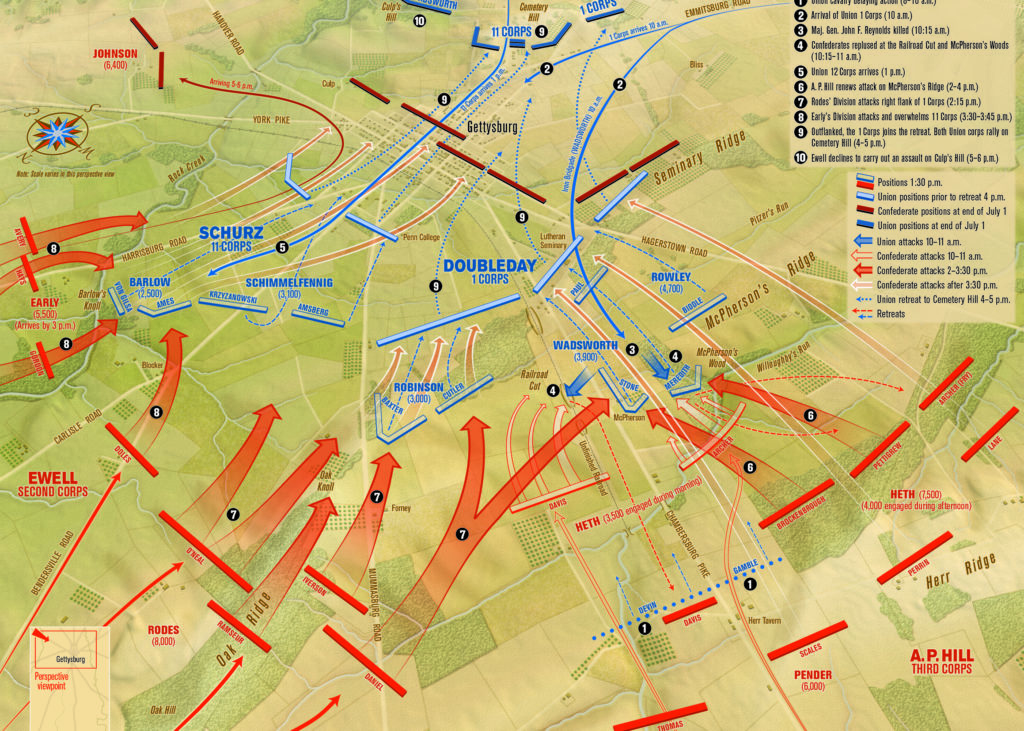

On June 28, Ewell’s three-division corps was positioned at Carlisle and York, Pa. When ordered to concentrate in the Cashtown–Gettysburg area, he sent Maj. Gen. Edward Johnson’s Division back down the Cumberland Valley toward Chambersburg, troops led by Maj. Gen. Robert Rodes, below, moved south from Carlisle, and Maj. Gen. Jubal Early’s men marched southwest from York. When his division was north of Gettysburg on July 1, Rodes heard the sounds of fighting between Maj. Gen. Harry Heth’s Division of A.P. Hill’s corps and the Union 1st Corps. He marched his division south and deployed on Oak Ridge, incorrectly thinking he was on the Federals’ right flank. Rodes had the choice either to assume a defensive position and wait for the army to concentrate (as Lee had instructed) or attack.

Rodes, with Ewell’s concurrence, disregarded Lee’s order not to bring on a general engagement and attacked. After his first attack failed, Rodes launched a second assault. The attacks brought Early’s Division into the fight and caused the commitment of an additional division from Hill’s Corps. Although they were eventually successful, four divisions of Lee’s army had been committed prematurely to battle. This resulted in a piecemeal deployment of the remainder of the army as it arrived on the field and prevented Lee from using the full power of his force.

8. Ewell Decides Not to Attack Cemetery Hill — Corps-Level Tactical Decision

The successful attacks by Ewell’s and Hill’s Corps drove the Union 1st and 11th Corps back through the town to Cemetery Hill. Lee directed Ewell to capture this key terrain, but not to bring on a general engagement. Rodes’ Division of Ewell’s Corps had already incurred heavy casualties. Two brigades of Early’s Division had been sent east to block a rumored enemy force on the York Pike, and Maj. Gen. “Allegheny” Johnson’s Division was still marching toward Gettysburg. When Ewell asked A.P. Hill for assistance, Hill contended that his divisions were not capable of further offensive action that day, leaving Ewell with only two brigades of Early’s Division for an attack on Cemetery Hill, where the Federals had already established a strong defensive position.

Ewell could either attack or remain in position and wait for the rest of his corps to join him—he chose not to attack, a decision that completed the fighting on July 1. As a result, Union troops continued to occupy and reinforce Cemetery Hill and Culp’s Hill, giving Meade a strong position with interior lines and impacting Lee’s offensive options for July 2.

9. Meade Orders His Army to Gettysburg — Army-Level Operational Decision

Although two Army of the Potomac corps fought on July 1, there was no guarantee that Meade would advance his other five corps to the battlefield as he did. Meade had several other options for where he could concentrate his army, though they all required the two corps at Gettysburg to march southward and break contact with Lee’s army. This decision would bring both armies to Gettysburg.

10. Lee Decides to Attack — Army-Level Tactical Decision

Although two Army of the Potomac corps fought on July 1, there was no guarantee that Meade would advance his other five corps to the battlefield as he did. Meade had several other options for where he could concentrate his army, though they all required the two corps at Gettysburg to march southward and break contact with Lee’s army. This decision would bring both armies to Gettysburg.

Although two Army of the Potomac corps fought on July 1, there was no guarantee that Meade would advance his other five corps to the battlefield as he did. Meade had several other options for where he could concentrate his army, though they all required the two corps at Gettysburg to march southward and break contact with Lee’s army. This decision would bring both armies to Gettysburg.

11. Longstreet Orders a Countermarch—Corps-Level Tactical Decision

Lee decided that Longstreet’s two divisions on the field (Maj. Gen. George Pickett’s Division had not yet arrived) would launch the main attack against the Union left flank. That required Longstreet’s troops to march south and attack without being seen. During that march, however, the lead brigade arrived at a small ridge that, if crossed, would expose Longstreet’s march to a Union signal station on Little Round Top.

Longstreet could either continue to march and be exposed, or countermarch and find a new route. He ordered his column to countermarch and find lower ground for the continued move south. This critical decision created a traffic jam that extended the time required to reach the attack positions. That pushed the attack off until late afternoon, disrupted the coordination and readiness of the remainder of the army to join the attack, and provided additional time for Maj. Gen. John Sedgwick’s 6th Corps to arrive and reinforce Meade’s defensive alignment.

12. Sickles Moves Forward — Corps-Level Tactical Decision

On July 2, Maj. Gen. Daniel Sickles’ 3rd Corps was defending ground that extended from Little Round Top northward to the left of Maj. Gen. Winfield Scott Hancock’s 2nd Corps on Cemetery Ridge. As such, his corps served as the Union army’s left flank. Sickles, however, did not like his position and turned his attention to a 40-foot higher plateau 1,400 yards to his front along the Emmitsburg Road. He sent Brig. Gen. Andrew Humphreys’ division to the Emmitsburg Road, while Maj. Gen. David Birney’s moved west to take up positions that snaked from Devil’s Den, through the Wheatfield, and out to the Emmitsburg Road.

That left Sickles with an unprotected right flank and his left flank detached from Little Round Top.

13. Longstreet Attacks the Union Left — Corps-Level Tactical Decision

After completing the countermarch, Longstreet’s units arrived on the southern extension of Seminary Ridge expecting to find themselves on the Union army’s left flank along the Emmitsburg Road. Instead, Longstreet found a Union force directly on his front, running from Devil’s Den through the Wheatfield to the Peach Orchard, and then along the Emmitsburg Road.

Longstreet had the options to launch an immediate attack on the Union position, led by Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws’ Division and supported by Maj. Gen. John Bell Hood’s Division, or he could re-deploy his two divisions to flank the Union defenses—to comply with Lee’s tactical intentions that day. When Hood presented a plan to shift his division farther southeast, Longstreet rejected it and ordered the attack to commence. This decision ensured there was an attack on July 2.

14. Law Goes for the Artillery, July 2 — Brigade-Level Tactical Decision

Hood deployed his four-brigade division in two lines. Jerome B. Robertson’s Brigade and Evander M. Law’s Brigade, from left to right, formed the attacking first line, followed by the supporting line of George T. Anderson’s Brigade and Henry L. Benning’s Brigade, from left to right. In this configuration, Law’s Brigade was not only the right brigade of Hood’s Division but also of the entire Army of Northern Virginia. With all five regiments deployed, the center regiment would maneuver straight to Big Round Top, then on to Little Round Top. As Law’s Brigade advanced, it came under artillery fire from Captain James Smith’s battery near Devil’s Den. Law had various options: Continue moving eastward; incline his entire brigade toward Devil’s Den; or send part of his brigade to attack Smith’s guns and continue forward with the remainder of his force.

Law directed his right two regiments, the 44th Alabama and the 48th Alabama, to move left behind the brigade and attack north toward the Union battery. What had been the center regiment, the 15th Alabama, was now on the brigade’s far right, heading directly toward the valley between Big Round Top and Little Round Top, with the 47th Alabama on its left. The story of the epic defense by Colonel Strong Vincent’s brigade on Little Round Top is well known, as they fought the Alabamians to a standstill. But had the two regiments Law had sent to the left been in position to support the main attack on Little Round Top, the fight for this vital terrain might have turned out differently.

15. Benning Follows the Wrong Attack, July 2 — Brigade-Level Tactical Decision

Law’s decision to divert two of his regiments had other critical implications. Benning’s Brigade had been deployed to support Law’s attack. A line of woods separated the two brigades, however. After passing through these woods into the open, Benning saw troops to his left front, but he wasn’t sure who they were. Benning had the option to stop his brigade until he could determine the identity of these troops or he could follow them. He decided to follow.

The troops turned out to be the two regiments Law had sent to attack Smith’s battery. But by following them, Benning’s Brigade was now in the fight for Devil’s Den and not in position to reinforce the attack on Little Round Top.

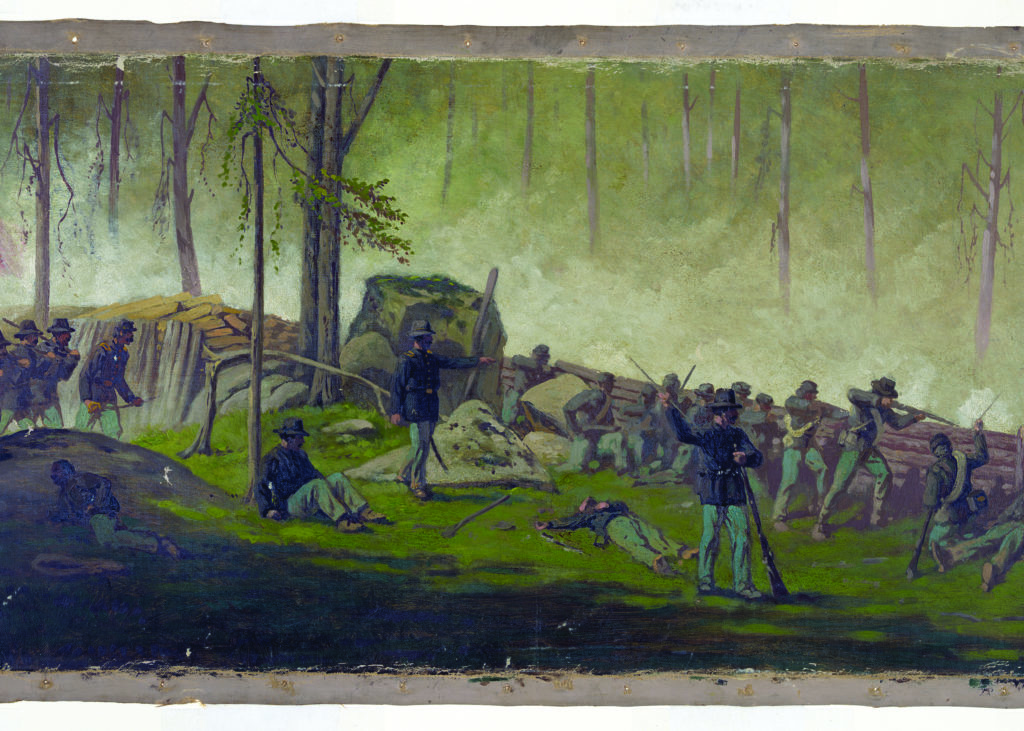

16. Greene Remains on Culp’s Hill, July 2 — Brigade-Level Tactical Decision

On the afternoon of July 2, the six brigades of the 12th Corps’ two divisions were on Culp’s Hill. A Confederate attack on the weakened Union center and left-center forced Meade to order those two divisions to leave Culp’s Hill and reinforce the threatened  Union position on Cemetery Ridge. But as Brig. Gen. George S. Greene’s 3rd Brigade, the last to depart, was preparing to move, Greene, left, received information from his pickets that a substantial Confederate attack was developing against his position. Greene had two choices: Follow Meade’s orders and march off Culp’s Hill or remain in position.

Union position on Cemetery Ridge. But as Brig. Gen. George S. Greene’s 3rd Brigade, the last to depart, was preparing to move, Greene, left, received information from his pickets that a substantial Confederate attack was developing against his position. Greene had two choices: Follow Meade’s orders and march off Culp’s Hill or remain in position.

Greene disobeyed orders and occupied the highest point of the hill. With assistance from the remnants of Brig. Gen. James Wadsworth’s 1st Division from the 1st Corps, Greene succeeded in holding much of the hill until 12th Corps units returned as reinforcements. Greene’s resolve kept “Allegheny” Johnson’s Division from capturing this key terrain, which would have allowed the Confederates to gain control of the Baltimore Pike and place a large force in the Army of the Potomac’s rear. The decision that secured the Union right had a major impact on Lee’s tactical decisions for July 3.

17. Slocum Decides to Attack — Corps-Level Tactical Decision

On the night of July 2-3, Maj. Gen. Henry W. Slocum (acting as a wing commander) was informed of Confederate forces close to and occupying portions of Culp’s Hill. Slocum could have ordered his troops to consolidate and form a defensive position along and east of the Baltimore Pike or he could order a counterattack to regain lost terrain.

Slocum decided to counterattack and ordered acting 12th Corps commander Brig. Gen. Alpheus S. Williams to attack at first light to recapture the lost ground. Williams’ attack preceded a planned attack by General Johnson’s reinforced division. As a result, Johnson became decisively engaged until about 10 a.m. This prevented Lee from being able to use this division when he developed his plan of attack for July 3.

18. Lee Continues to Attack — Army-Level Tactical Decision

Lee believed he might have been successful on July 2 if his army’s three corps had operated in a coordinated fashion, and on July 3 he still had the same tactical options as the day before.

Lee’s initial plan to continue attacks on both Union flanks proved unworkable, so he decided to attack the Union center—what is known as the Pickett-Pettigrew-Trimble Charge or, more popularly, “Pickett’s Charge.” It would be the last of Lee’s attacks at Gettysburg, a thorough Confederate defeat with extensive casualties. Each of Lee’s divisions had been involved in heavy fighting and taken severe casualties.

19. Meade Does Not Counterattack — Army-Level Tactical Decision

The defeat of Lee’s attack against the Union center provided Meade with an opportunity to counterattack or to remain on the defense. The Federals had also suffered significant casualties in three days of fighting, and Meade’s losses among senior commanders had been severe and disruptive of his army’s structure. In addition, Meade had just witnessed the effect that strong defensive fire had against an enemy advancing over open ground. He decided not to repeat Lee’s mistake and didn’t order a counterattack. Meade’s critical decision brought an end to all major combat in the vicinity of Gettysburg.

20. Lee Decides to Retreat — Army-Level Operational Decision

Lee had lost approximately 34 percent of his army over the three days of fighting. Ammunition was low with no resupply available north of the Potomac River; water was becoming scarce; and his ability to resupply was severely curtailed. Lee made the critical decision to retreat to Virginia. Executing this decision would be the first step in terminating the campaign.

_____

Matt Spruill is a former Licensed Gettysburg Battlefield Guide, who now resides and writes from Colorado. The critical decisions he summarizes in this article can be fully explored in his new book, Decisions at Gettysburg: The Twenty Decisions That Defined the Battle, 2nd Edition, published as part of the University of Tennessee Press’ newest series, “Command Decisions in America’s Civil War.”

This story appeared in the August 2020 issue of Civil War Times.