The Japanese invasions of the Philippines, Malaya and Singapore were swift and brutal, giving imperial Japan control over most of the Pacific by the end of January 1942. On February 19, Japanese carrier planes raided the northern Australian city of Darwin, in what was considered a prelude to an invasion. Throughout the Commonwealth, Australians braced themselves for a desperate fight for their homeland. In the months that followed, there would be dozens of additional air raids on the island continent.

So when the Brisbane police began getting phone calls from citizens claiming that Japanese Zeros were flying overhead in 1943, the authorities chalked it up to nerves. Any airplanes operating over the city were from the nearby military airfield at Eagle Farm, they told the anxious callers, and they all belonged to the good guys. In fact, the police were only half right. That was a Zero soaring overhead—flown by an Allied pilot. What’s more, there were other Japanese aircraft stored in a hangar at Eagle Farm, participants in a top-secret operation that would prove instrumental in turning the tide in the Pacific air war.

In the early days of World War II, the Allies possessed scant intelligence about Japanese air power or aircraft. Tight budgets, which limited intelligence gathering, a preoccupation with the German threat in Europe and a dismissive attitude toward the Japanese combined to result in an information void. In December 1941, Pearl Harbor proved the folly of that mistake.

Correcting the oversight became the responsibility of the newly formed Technical Air Intelligence Unit (TAIU). Authorized by Maj. Gen. George Kenney and supported by General Douglas MacArthur, this team of U.S. Army Air Forces, U.S. Navy, Royal Australian Air Force and Australian Army personnel took on the job of recovering, rebuilding and flying downed or captured Japanese aircraft. To run the operation, MacArthur tapped Major Frank McCoy, an Oklahoma born lawyer whose tough, logical thinking was masked by courtly manners. McCoy recruited Lieutenant Clyde Gessler, an engineer with a near-photographic memory and a knack for figuring out where some odd fragment might fit into the overall picture. Armed with letters signed by MacArthur giving them carte blanche for whatever equipment, personnel or transportation they needed, the team set off to sites where Japanese airplanes, or pieces of planes, could be found.

Initially the wreckage the TAIU salvaged came from planes downed behind friendly lines. Usually these were discovered deep in the jungle, where simply spotting a wreck, much less recovering it, was an achievement. But as the Allies began to push the Japanese off their island strongholds, the TAIU team also started collecting aircraft abandoned at airfields.

Moving the aircraft demanded equal parts ingenuity and brute force, especially in the tropical heat and humidity typically experienced on Pacific islands. Team members had to manhandle the fuselage, engines and other components onto barges, then float them out to ships for transport to Australia.

Gessler kept a wartime diary, which though informative is generally sparse on details due to security concerns. He does complain, however, about some of the difficulties the teams encountered, like the time when a fully loaded barge sank and they had to try to recover the engines, airframes, tail sections and wings on it using little more than a portable A-frame crane and swimmers who could hold their breath for a long time. Once the bits and pieces arrived in Brisbane, mechanics, draftsmen, avionics technicians and airframe and power plant specialists all went to work in Eagle Farm’s Hangar 7. The airfield was a major military facility where many Allied operations were headquartered. Located away from most of the action on the field, Hangar 7 was positioned 90 degrees from the other hangars, so outsiders couldn’t see much. Inside it was part aircraft factory and part storage depot, where technicians and mechanics worked to reconstruct the wrecks.

Often as not, soldiers had scavenged the wreckage before the TAIU team arrived, which made it even harder to put the puzzle pieces together. Then there were the challenges resulting from cultural differences. Japanese engineers often approached aeronautical and mechanical problems from a different mind-set than Allied engineers, and few personnel could decipher Japanese, so any written information found on the components was largely useless.

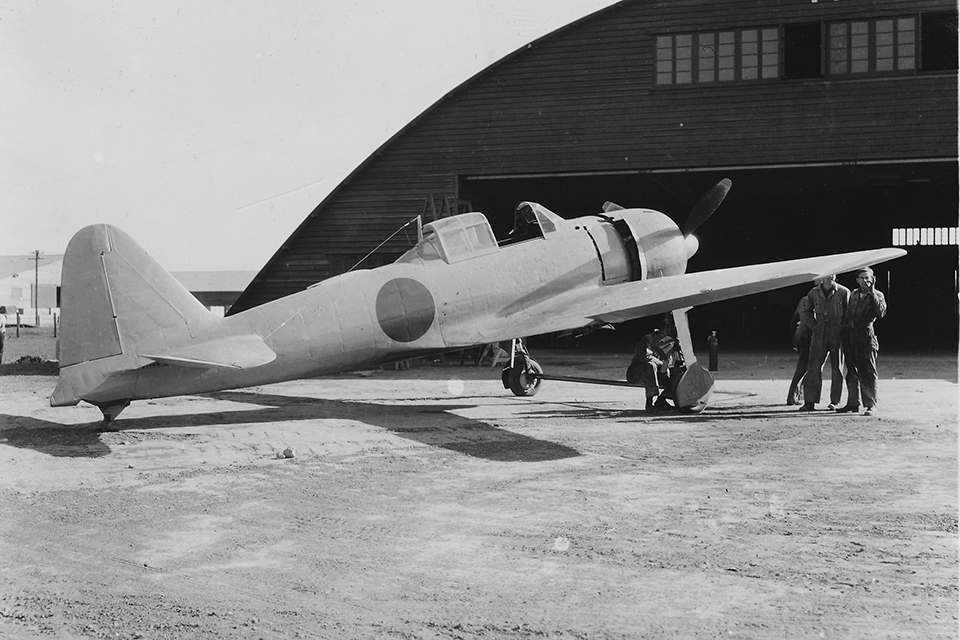

The secrecy of the project was inevitably breached (and the frantic phone calls to the Brisbane police began) once the reconstructed planes became airworthy. On July 20, 1943, Captain William Farrior took off in a Mitsubishi A6M3 Model 32 Zero, accompanied by Allied aircraft flying shotgun to prevent some sharp-eyed pilot who wasn’t in on the secret from shooting him down. Base personnel had by this time learned a bit about what was going on in the half-hidden hangar. There are stories of work stopping on the base whenever Hangar 7 planes were flying, with airmen looking on as Zeros and a Nakajima Ki.43 Hayabusa fighter engaged in mock dogfights with P-47 Thunderbolts and Spitfires.

According to Gessler’s diary, the pieced-together planes were tested for speed, rate of climb, maximum altitude, diving, maneuverability, fuel consumption, range, horsepower and fuel efficiency. The team promptly passed on information about the enemy aircraft’s capabilities and vulnerabilities to Allied aircrews and airplane designers, who were quick to exploit the intelligence.

One of the most important aspects of the TAIU’s work was developing accurate visual recognition materials and identification names for enemy planes. In most cases the Japanese designations were either unknown or unpronounceable to Allied troops. McCoy called on Tech. Sgt. Francis Williams to find a way to make it easier for Allied personnel to quickly identify and report sightings via code names. Williams suggested using common first names: male names for fighters and floatplanes; female for bombers, reconnaissance aircraft and flying boats; and names starting with “T” for transports. Most of the names came from friends and family members: Betty, Fred, Nate. The Zero became Zeke; the Hayabusa became Oscar. One of the first names selected did not stick. When Hap was chosen to honor General Henry “Hap” Arnold, he was less than flattered. The name was revised to Hamp, but eventually finalized as Zeke 32, since it was essentially a clipped-wing Zero variant.

Paired with accurate silhouettes of the planes, the new recognition scheme—officially the MacArthur Southwest Pacific Code Name System—grew to more than 50 names. McCoy would later be called on to develop a similar naming system for Soviet aircraft during the Korean War.

The TAIU project initially focused on flying capabilities, but it also gathered other information. Analysis of metallurgy told where core materials had been mined. Data plates identified manufacturing plants and gave rates of construction, data that went to mission planners organizing bombing raids.

In 1944 the project moved to Anacostia. Fighters, bombers, recon planes and transports also went to other locations for testing and evaluation. Most of those aircraft were later scrapped, but a few went to museums, including the National Air and Space Museum and the National Museum of the U.S. Air Force.

McCoy and Gessler remained lifelong friends. Typical of their generation, they rarely mentioned their wartime activities to their families. After Gessler’s death, his daughter discovered a Zero instrument panel in his garage. It seems his mechanics had given it to him as a farewell gift. McCoy’s son now has the letters that General MacArthur signed, authorizing the TAIU team to take whatever they needed, hanging on a wall in his home.

As for Hangar 7, it still stands—near the edge of what is now Brisbane International Airport. Today the Eagle Farm Aviation Society, dedicated to the history of the TAIU, hopes to see it restored as a museum chronicling the secret project that put Zeros in the skies over Brisbane.

Fran Severn is a freelance writer, editor and pilot with more than 300 published articles to her credit. For more information about the TAIU, visit the Eagle Farm Aviation Society website at hangar7.org.au.

Originally published in the July 2014 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.