Before Billy Mitchell, Bomber Harris and Curtis LeMay, there was Peter Strasser, history’s first— and seemingly most unlikely— proponent of strategic bombing. Strasser’s weapons were the most hazardous bomb delivery systems ever put into the air: huge, cumbersome, hydrogen-filled airships.

Strasser began his remarkable career by enlisting in the German navy at age 15. He served on the converted training ships Stein and Moltke, revealing a talent for gunnery, then enrolled in the naval academy at Kiel and was commissioned a lieutenant at 19. His outstanding ability as a gunnery officer led to an assignment with the shipboard ordnance department of the admiralty in Berlin.

Strasser made an unusual career move in 1911, volunteering for aviation service. By that time he was a 35-year-old Fregat ten – kapitän, equivalent to a U.S. Navy commander. His request lay dormant for two years. The man then masterminding the updating of Germany’s navy, Grossadmiral Alfred von Tirpitz, was no airship advocate until his sea captains began to tout the “gasbag’s” scouting value. That, plus the success of Germany’s commercial airships and possibly pressure from Kaiser Wilhelm II, led to the navy’s signing a contract with the Luftschiffbau Zeppelin Company for construction of an airship. Designated L-1, it was delivered in September 1912. During its 68th flight, on September 9, 1913, L-1 was battered into the North Sea by a storm, killing 14 of the 20 aboard. Among those lost was Korvettenkapitän Friederich Matzing, chief of the recently formed Naval Airship Division. Two weeks later Matzing’s successor was ap – pointed: Peter Strasser.

Strasser initially regarded his ascension to the head of the tiny Airship Division as something of a demotion. But he threw himself into his new assignment, quickly determining that the airship’s potential lay far beyond its current conception as a flying observation platform serving the surface fleet. Strasser arranged for airship flying lessons with Ernst A. Lehmann, captain of the commercial airship Sachsen. The Zeppelin-built airship was operated by Deutche Luftschiffarts AG, known as DELAG, the nation’s highly successful airship passenger line.

While Strasser learned airship-manship from the man who would die in the 1937 Hindenburg disaster, the navy’s second airship, L-2, underwent flight testing. On October 17,1913, during its 10th flight, L-2 caught fire and plunged to the ground, killing all 28 aboard. Barely three weeks after assuming command, Strasser had no airships.

He pressed the admiralty to temporarily employ Sachsen as a naval training ship, with DELAG’s Hugo Eckener and Ernst Lehmann heading flight operations. By early December 1913, the Airship Division was back in the air, with Sachsen making frequent flights under Eckener’s direction. This unusual shared command between a civilian contractor and a career officer proved remarkably compatible, despite Strasser’s tough reputation.

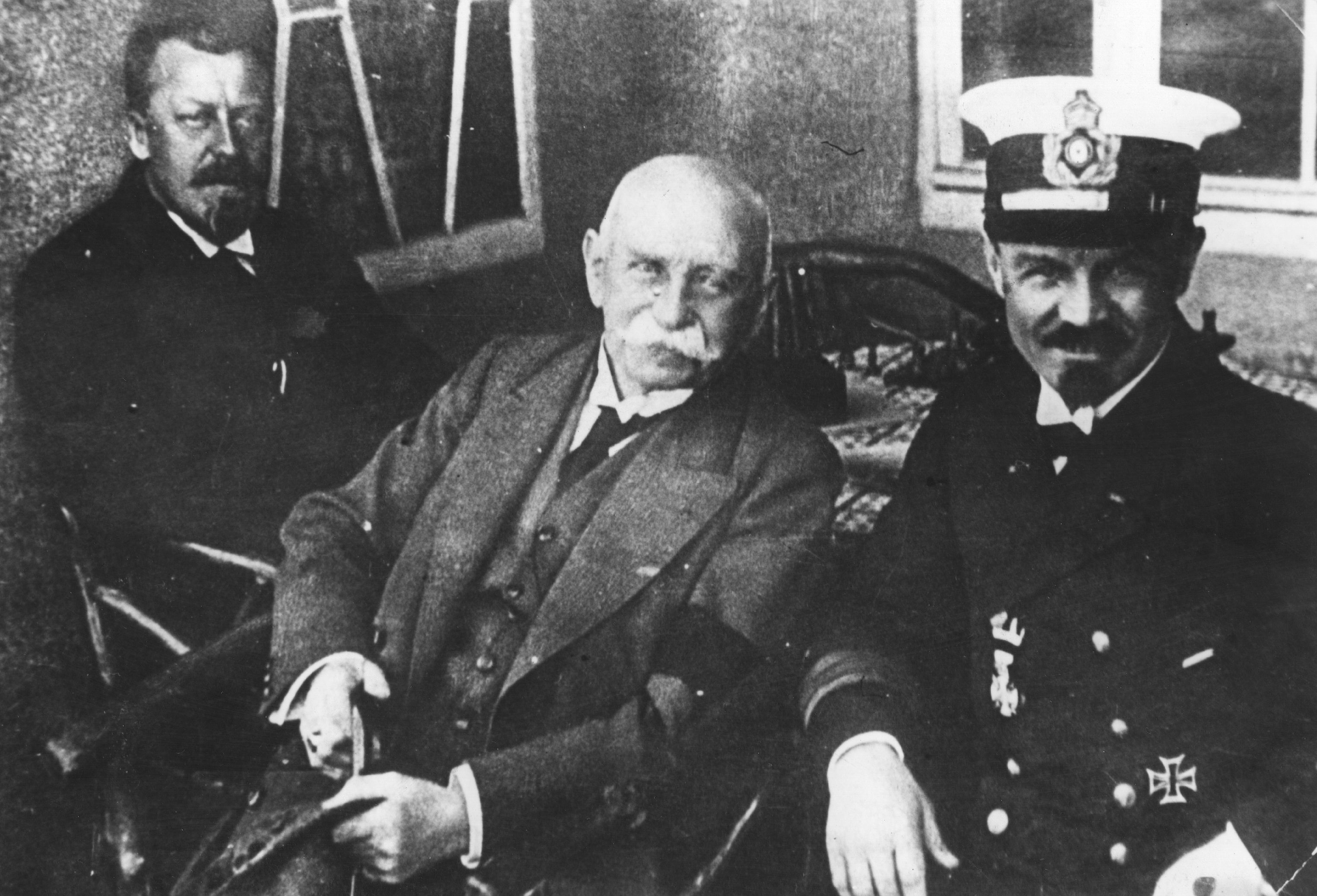

Short, with pixielike ears, wide-set piercing eyes and a dapper moustache and goatee, the Airship Division commander was renowned as a spit-and-polish disciplinarian. Any lapse might bring an offender before him for a nerve-twitching rant, the navy’s dreaded “black cigar.” Off duty, Strasser showed concern for his officers and men—an attitude that served him well as he undertook to sell the tradition-bound navy on a new kind of warfare with an unproven new weapon. And compared to the combative Billy Mitchell, who fought to convert the tiny post–World War I U.S Army Air Service into a primary strike force, Strasser was more likely to schmooze with superiors rather than antagonize them.

When World War I started in August 1914, Strasser commanded a total of 12 officers and 340 enlisted men, among them only three qualified flight crews. His available weaponry: a single airship, the Zeppelin-built L-3. Strasser’s greatest asset was the admiralty’s realization that an airship could be built in a mere six weeks, compared to a cruiser’s two-year construction time, which ensured a ready supply of gasbags. By the end of that year, his command had expanded to five airships and more than 4,000 officers and men, including 25 flight crews, at nine bases.

Strasser pledged to regularly fly in combat. On January 19, 1915, he headed for England aboard L-6, but 90 miles short of the goal a crankshaft shattered and L-6 had to limp back to base. Aboard L-7 on April 15, when he led a three-Zeppelin attack on targets near the mouth of England’s Humber River, a powerful headwind forced the plodding Zeppelins to abort short of the target. Such mishaps led to Strasser’s being labeled a bad luck “Jonah.”

The destruction of the German army Zeppelin LZ-37 by a Morane-Saulnier parasol monoplane on June 7, 1915, dramatized the perils associated with the 6,000-foot service ceilings of Strasser’s airships. Modifications increased service ceilings to 13,000 feet, and in December 1916 Strasser informed the admiralty that more changes could raise the ceilings even further, resulting in the Zeppelins the British called “height climbers,” with 16,000- to 20,000-foot ceilings. They left the British anti-airship forces almost defenseless until the last few months of the war, when improved fighters could finally reach them.

Strasser stepped up naval airship attacks on English targets throughout the next several months. On September 2, 1916, he ordered what would be the largest airship raid of the war: 12 navy and four army airships. The loss of one airship near London heartened the British and proved a turning point. German army airships did not attack England again, and the army disbanded its airship service some months later.

Despite the flaming destruction of two training airships on the ground two weeks later and the loss of two more a week after that, Strasser seemed undaunted. On March 16, 1917, he ordered the first attack on English targets by the new height climbers, which cost the Airship Division its just-built L-39. Blown eastward by a gale after dropping six bombs on Kent, it was shot down by French anti-aircraft gunners. Of even greater significance was growing interest in the twin-engine biplane Gotha bomber in early 1917. Although it carried about a third of a height climber’s bombload, the Gotha required a crew of three, needed no multiman ground force and constituted a much smaller target.

The only advantage left to the airships was their far greater range. In the face of morale-crushing losses and the ascendancy of bomb-carrying planes, Strasser continued his campaign. On May 24, 1917, he was aboard L-44 when all five engines started intermittently shutting down. Jonah had struck again.

The high-altitude Zeppelins were now attacking at 20,000 feet, untouched by antiaircraft fire, above enemy aircraft ceilings and higher than searchlights could reach. Now they faced a new problem: thin air. Liquid compasses froze, control cables slackened, the compressed oxygen provided for intermittent whiffs was often contaminated and crewmen who declined to use it often collapsed. When liquid air replaced the original compressed oxygen, that problem was alleviated.

All to little avail.

On August 4, 1918, with the war obviously lost, Strasser led the first raid on England since April. At twilight he radioed five Zeppelin commanders to attack—the last order he ever gave. An hour later, nearing the English coast, L-70 was shot down by a de Havilland D.H.4. All 22 crewmen aboard the airship died. The British buried Peter Strasser at sea.

With his death, the use of airships as strategic weapons ended. In 51 airship raids (including several by army airships), 557 people on the ground had been killed and 1,358 wounded. Damage to British property was estimated at $7.5 million. The German navy had lost 389 Zeppelin crew members, a 40 percent death rate. Of its 73 airships, 53 were destroyed by enemy action or accidents.

The most significant effect on Britain’s war effort was the withdrawal or retention of fighter squadrons for home defense. By the end of 1916, before the Gotha raids began, 17,341 officers and men were assigned to home defense, 12,000 of them in anti-aircraft units, the balance in 12 Royal Flying Corps squadrons totaling 110 airplanes.

The strategic bombing pioneer died in the weapon he had championed. But Peter Strasser’s concept of long-range strikes at the enemy’s homeland lived on—with a vengeance. Twenty-seven years later, Germany lay in ruins as a result of strategic bombing.

Originally published in the November 2008 issue of Aviation History. To subscribe, click here.