‘Custer had his victory, an even though a search party had not found Elliott’s missing detachment, Custer was determined to leave before the Indians could turn his triumph into something quite the opposite’

As twilight turned to daylight on November 27, 1868, the opening notes of “Garryowen” sounded from a height just north of the Washita River in western Indian Territory (present-day Oklahoma). This marching song of the 7th U.S. Cavalry was the signal for more than 700 cavalrymen to converge on a 50-tepee Cheyenne village in a loop along the river’s south bank. As his buglers sounded the charge, Lt. Col. George Armstrong Custer led the assault, his black horse splashing at full gallop through the water at the head of Companies A, C, D and K.

It was a rude awakening for Chief Black Kettle and his villagers, who fled from their lodges, adding a chorus of screams and war whoops to the din of pounding hooves and relentless revolver and carbine fire. Women and children, most half-clad and barefoot, were among those cut down trying to escape in the snow. Although shaken and disorganized, many of the warriors grabbed their weapons—bows and arrows as well as rifles—and fired back at the bluecoats. Not all of the Indians would die easy this bitter fall day. The Cheyenne defenders killed Captain Louis Hamilton in the initial charge, and later severely wounded Captain Albert Barnitz.

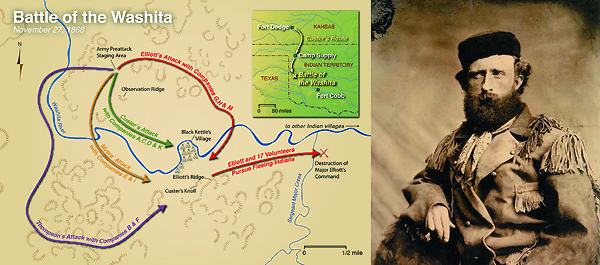

Custer shot one warrior in the head but did not linger amid the chaos. He streaked through the village and took station on a hillock a quarter mile south of the Washita in order to direct the movements of his regiment. Major Joel Elliott, leading Companies G, H and M, had converged on the village from the northeast, entering it about the same time as Custer’s command. Captain Edward Myers took Companies E and I into the village from the west after the shooting started. Captain William Thompson arrived late from the south with Companies B and F, leaving a gap between his command and that of Elliott through which many Cheyennes escaped. (See map, above.)

Within 10 minutes of the initial assault the 7th Cavalry controlled the camp; but dismounted troopers exchanged fire with desperate warriors for several hours in the woods along the riverbank. Major Elliott, the second in command, stationed himself on a ridge near the knoll Custer was using as the regimental command post. But he didn’t remain there long. Spotting a group of Indians fleeing downstream, Elliott galloped after them with 17 volunteers from various companies. None returned. A search party came up empty, and ultimately Custer left them behind, as too many other hostile Indian villages lay close by to justify lingering in the area.

Custer’s rout of Black Kettle’s village has since generated plenty of controversy. But a bigger concern for the 7th Cavalry itself over the following eight years was the question of whether or not Custer had abandoned Elliott. Captain Frederick Benteen and other 7th Cavalry officers could not forget what Custer did or didn’t do at the Washita in 1868, and they could not forgive their commander. The regiment was divided over the issue, setting the stage for other conflicts that disrupted the 7th Cavalry right up to the death of Custer and his immediate command at the Little Bighorn in Montana Territory on June 25, 1876. Only then did the Elliott affair cease to be a festering sore, for the 7th Cavalry lay deep in its own blood.

Born on October 27, 1840, Joel Haworth Elliott was the second son and third child of Mark and Mary Elliott. He grew up on the family farm near Centerville in Wayne County, Ind. His parents were fervent Quakers. In 1860, at age 19, he attended nearby Earlham, a Quaker teachers college, and also taught school in the area. But in the fall of 1861 he did not return to Earlham or continue teaching. Instead, as Sandy Barnard explains in his biography A Hoosier Quaker Goes to War, Elliott made a decision that ran counter to the pacifist tenets of Quakerism: On August 28, 1861, he enlisted as a private in Company C, 2nd Indiana Volunteer Cavalry Regiment.

Elliott’s decision likely concerned his family, but he was a product of his times. Like so many other young men at the outset of the Civil War, he had been swept up in the military moment and sought out adventure, honor and glory. He had also been influenced by prominent Wayne County lawyer George Washington Julian, himself a Quaker, founder of the Republican Party in Indiana and later a six-term U.S. congressman. A committed abolitionist, Julian had reinforced Elliot’s own Quaker antislavery views.

For the next 19 months the young Quaker-turned-soldier served the Union, much of that time detached from his regiment as an orderly/aide for senior field-grade officers such as Maj. Gen. Alexander McDowell McCook. In that capacity Elliott was at the Battles of Shiloh, Perryville and Stones River. In June 1863 he was commissioned a second lieutenant in the newly formed 7th Indiana Volunteer Cavalry Regiment and served as a recruiting officer. He quickly rose to first lieutenant and in October was commissioned captain of Company M.

In February 1864 Elliott and his regiment joined Brig. Gen. William Sooy Smith’s command, which was supporting Maj. Gen. William Tecumseh Sherman’s march to Meridian, Miss. Smith’s force was to keep Maj. Gen. Nathan Bedford Forrest’s Confederates from interfering with Sherman’s operation, and the two sides clashed at Okolona, Ivy Farm and Pontotoc. On February 22 Elliott led his company as part of a mounted saber charge by the 7th Indiana and 4th Missouri Cavalry regiments at Ivy Farm. The enemy was forced to retire from the field but not before the young officer had a horse shot from under him and received a pistol wound to his neck.

Elliott and his comrades battled “that Devil Forrest” again at Brice’s Crossroads, Miss., on June 10, 1864. A Confederate onslaught on the Federal line routed the Yankees, and Elliott sustained gunshot wounds to his left lung and shoulder. After getting away from the pursuing Confederates, Elliott returned to his Indiana home to recuperate for the next six weeks.

In September 1864 Elliott re-joined his regiment near Memphis, and in December he led a 7th Indiana detachment in cavalry raids at Verona and Egypt, Miss. He and his men captured hundreds of supply wagons, four locomotives and 500 enemy prisoners. Elliott had done his part to end slavery and do the same for the Confederacy, but he was not about to give up the life of a soldier.

At war’s end the 7th Indiana was transferred into a corps of observation along the Texas frontier, intended to intimidate the French-supported Mexican government. Captain Elliott and his regiment became part of Brevet Maj. Gen. George A. Custer’s cavalry division stationed at Austin. While serving in the Lone Star State, according to author Barnard, Custer and Elliott enjoyed a good relationship. “What is evident during this period is that Captain Elliott obviously struck up, if not a close personal friendship with George Custer, at least a close professional tie,” writes Barnard. “Elliott frequently was appointed to boards of survey and other administrative positions in the command. For a time in December 1865 Elliott served as the command’s judge advocate, handling general courts-martial for Custer.”

Mustered out of the service in 1866, Elliott sought an appointment as a regular officer in the Army. Among his supporters were Rep. Julian, Sen. Oliver P. Morton of Indiana and his old commanding officer and Civil War hero Custer. In a letter of recommendation addressed to the War Department in December 1865, Custer said Elliott was “eminently qualified to hold a commission in the Regular Army,” and called him “a natural soldier improved by extensive experience and field service.” But not until March 11, 1867, was Elliott appointed a major in the 7th Cavalry.

Elliott joined his new regiment at Fort Riley, Kan., again serving under Custer, a lieutenant colonel in the postwar Army though still referred to as “General” by his men. What followed was a summer of frustrating forays designed to chastise the Cheyennes and Sioux for their depredations in Kansas, Nebraska and what would soon become Wyoming Territory. When Custer’s superiors relieved him of command and court-martialed him for leaving his regiment without permission, Elliott, as the senior regimental officer fit for duty, took charge of the 7th. One historian described the major as “a pleasant and earnest youth, with a high fair forehead beneath wavy hair and a studious face framed by sideburns.”

For the next 15 months the regiment patrolled the Kansas plains in operations characterized by, in the words of 7th Cavalry Captain Albert Barnitz, “long, exhausting marches, heat, dust, bad water and the absence of Indians.” In a letter home the captain recalled Elliott as a good commanding officer. “He has his faults to be sure,” Barnitz wrote, “but upon the whole he is an excellent officer.” In addition to field duty, for a time Elliott served as post commander at Fort Harker, Kan. But Custer was coming back.

In the fall of 1868 Maj. Gen. Philip H. Sheridan, commander of the Department of the Missouri, initiated a winter campaign to subdue the Indians on the central and northern Great Plains. Custer, found guilty at his court-martial, was serving a one-year suspension from rank and command, but Sheridan brought him back two months early to lead the 7th Cavalry on this campaign. With Custer again in charge, Elliott reverted to second in command of the regiment. The campaign proper began on November 12, but Custer didn’t take the field in pursuit of the Indians until the 23rd. On the 26th Elliott, whom Custer had dispatched with three companies on a scouting mission, picked up a recent Indian trail leading south from the Antelope Hills. By 9 o’clock that night Custer had linked up with Elliott’s command. In the early morning hours of November 27 an Osage scout discovered the village of Chief Black Kettle, a survivor of the Sand Creek Massacre, and Custer began preparing for his dawn attack.

Elliott did not notify Custer when he left the main battle with 17 volunteers to pursue fleeing Indians. As he galloped off, the captain called out to a fellow officer, “Here goes for a brevet or a coffin!” Once the shooting around the village had stopped, Custer had his men gather up Indian captives (53 women and children), burn tepees and supplies and shoot Indian ponies (nearly 900). Elliott was nowhere to be found, but Custer had bigger concerns. Assigned to round up the ponies, 1st Lt. Edward S. Godfrey had wandered a few miles down the wooded river valley. As the lieutenant summited a promontory to get his bearings, he spotted many more tepees and many more warriors heading in his direction. Custer had his victory, and even though the search party he had sent out under Captain Edward Myers had not found Elliott’s missing detachment, Custer was determined to leave before the Indians could turn his triumph into something quite the opposite. In a bold gambit he marched east from the late Black Kettle’s smoldering village, directly toward the newly discovered Indian villages. Believing the soldiers were intent on continuing the attack, the warriors switched to the defensive, dispersing down the valley to protect their families and lodges. The ruse worked. At nightfall Custer had his men reverse direction and ride clear of the valley.

Though none of Elliott’s group lived to tell the story, it isn’t hard to piece together a basic narrative (see sidebar, opposite page). The major’s rashness had led to a last stand that cost him and his men their lives. Eight years later others would insist that Custer’s own rash behavior led to the infamous Last Stand at the Little Bighorn. But this fall day at the Washita, Custer was intent on saving the rest of his command and in no rush to solve the mystery of Elliott’s lost detachment.

Indeed, thanks to Custer’s judicious behavior, his men and their Indian captives withdrew safely. To many Americans, Custer the Civil War hero was now Custer the Indian wars hero, but he drew criticism as well for his actions. Advocates of peace with the Indians decried his victory as a “massacre,” and his military peers questioned his judgment in attacking an enemy of unknown strength on unknown terrain.

Custer had more questions to answer that December after he, Sheridan and a force of some 1,700 men marched back to the Washita and discovered the mutilated remains of Elliott and his men. Captain Benteen, for one, said the tragedy happened because Custer had “abandoned” Elliott. Most others probably didn’t go that far, but some officers did question whether Custer had done enough to find and rescue his chief subordinate. Soldier casualties would have been light (four men killed and 13 wounded) if not for the death of Elliott and his 17 volunteers. Custer recorded 103 Indian warriors killed in the battle, although the Cheyennes claimed only 31 killed, 17 of those women and children. Regardless of the death toll on either side, the ghost of Elliott and his band would come to haunt the 7th Cavalry.

Benteen’s opinion about the Elliott affair first surfaced in a private letter forwarded to the Missouri Democrat and published on February 9, 1869. In high 19th-century melodramatic style Benteen described what he imagined to be the last moments of the forsaken men: “With anxious beating hearts, they strained their yearning ears in the direction of whence help should come,” he wrote. “What must have been the despair that, when all hopes of succor died out, nerved their stout arms to do and die?”

Benteen then claimed that his commander had remained in the Cheyenne village as his men rounded up prisoners, took inventory and slaughtered Indian ponies—perfunctory tasks at best—all the while oblivious to the plight of Elliott and his men and making no effort to search for them. Benteen’s claim, right or wrong, sprang from a rift that had plagued the regiment before the Washita and only widened after Elliott’s death: The 7th Cavalry officer corps was divided in its loyalties to its commanding officer. The accusatory letter from Benteen, self-anointed leader of the anti-Custer faction, did not initiate this conflict but merely brought it out into the open.

Throughout Custer’s tenure in the 7th Cavalry subordinates complained bitterly about his lack of recognition for the actions they performed on campaign. This included the commander’s report from the Battle of the Washita, in which he merely mentions the deaths of Hamilton and Elliott, the wounding of three other officers and that two officers (Benteen and Barnitz) had personally killed three Indians between them. Custer cited no other officer for his accomplishments that day, despite many praiseworthy examples.

One was Godfrey’s masterful three-mile leapfrog retreat with his platoon from the mass of warriors approaching Black Kettle’s camp from villages farther downstream. Moreover, Godfrey’s field report had alerted Custer to the threat of retaliatory Indian attacks. Custer also failed to cite the bravery and leadership of Captains Thomas Weir, Benteen and Myers during the 7th Cavalry’s withdrawal. These officers had met Indian charges with countercharges, forcing back the enemy and enabling the regiment to escape.

To top it all off, Custer never credited the late Elliott with finding the Indian trail that ultimately led to the discovery of Black Kettle’s village. Many in the 7th Cavalry ranks thought that omission in particular slighted the memory of a fallen comrade and revealed Custer could not be trusted, especially after the lieutenant colonel had seemingly abandoned Elliott at the Washita. If Custer could treat his second in command in such a fashion, would he not also ignore and betray their interests?

In his writings about the 1873 Yellowstone Expedition fights at Honsinger Bluff (August 4) and the Bighorn (August 11), Custer made only oblique references to his officers’ accomplishments, while highlighting his own actions and those of brother Tom. When approached about his refusal to acknowledge fellow officers in his reports, Custer replied that to single out exemplary individuals would be unfair to those not cited, and that among professional soldiers such laudatory remarks were unnecessary and unbecoming. But such acclaim in reports was a prime avenue toward promotion and honor; Custer had had his activities announced in numerous official Army communiqués, reports and newspapers during the Civil War, with great benefit to his career. Thus his excuse for slighting his officers was disingenuous at best.

Another point of contention was Custer’s practice of sharing with subordinates as little as possible about his intentions. First Lt. William W. Cooke, the regimental adjutant general, was firmly in the Custer “camp,” yet even he once exclaimed that when it came to being informed of critical matters, George never told him anything. Custer made officer calls—such as the one held before the attack at the Washita and through the Little Bighorn campaign—purely to give out instructions; input was neither requested nor tolerated. This approach to command did much to erode relations between Custer and key subordinates, stunting initiative and clouding mission objectives.

Custer’s prickly personality exacerbated problems with the officers and men in his command. According to John Burkman, the lieutenant colonel’s orderly, his boss had a tendency to overreact, “flying off the handle suddenly, maybe sometimes without occasion.” He did not have the capacity to counsel men on points of dissatisfaction, preferring to believe the officers would resolve such problems themselves. Even with brother Tom, George depended on wife Libbie to curb the younger Custer’s excessive drinking habits. By 1869 Custer had stopped caring whether his officers liked him; the criticism he had received over the loss of Elliott had helped push him in that direction. In a letter to Libbie that year he confessed, “I never expected to be a popular commander in times of peace.” His expectation was fully realized.

When the 7th Cavalry rode to the Little Bighorn—and death and glory—in June 1876, it was a military column fractured by internal dissent. Other such units on the frontier had their share of personality conflicts and cliques, but few to such a degree. The mistrust, resentment and fear of betrayal many 7th Cavalry officers harbored toward Custer were in no small part a result of the Elliott affair. Whether it adversely affected the regiment’s martial performance after the Washita is a point for de-bate. But certainly the regiment would have performed its frontier duties with more confidence and less second-guessing had it not been for all the suspicion and mistrust. Custer’s tragedy at the Little Bighorn dwarfed Elliott’s tragedy at the Washita, but it is impossible to forget or dismiss the obvious links between the two.

Maryland attorney Arnold Blumberg has indulged his passion for military history as a visiting scholar with the History and Classics Department at John Hopkins University in Baltimore. Suggested for further reading: A Hoosier Quaker Goes to War, by Sandy Barnard; The Battle of the Washita, by Stanley Hoig; Crazy Horse and Custer, by Stephen E. Ambrose; and Custer: The Controversial Life of George Armstrong Custer, by Jeffry D. Wert.