How an army of axmen helped the Allies win the air war

A few chilly days after Christmas 1917, the men of the U.S. Army’s 415th Aero Construction Squadron crept through foggy woods, all eyes out for their elusive enemy’s signature dull-gray uniform. The United States had entered the Great War eight months before. Most of these soldiers had enlisted because they were eager to fight in France. Instead, fate and bureaucracy had landed them 5,000 miles west, pioneers in a strange assault on the quiet coast of Washington state.

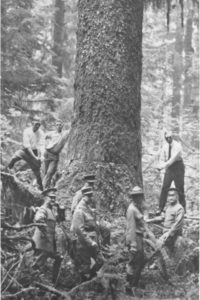

After hours wandering the profusion of Western hemlocks whose deeply grooved brown bark dominated the Olympic Peninsula rainforest, an eagle-eyed timber scout spotted the scaly gray skin of a 200-foot Sitka spruce. Unsheathing axes and crosscut saws, soldiers hacked steps a dozen feet up the tree’s 12-foot-diameter trunk and precisely carved notches into which the men wedged a pair of boards.

On each platform, a sawyer planted mud-caked boots and went at it with an ax, swinging from the shoulders to start the task of felling a giant that had towered over those soggy woods for three centuries. Soon the spruce’s sturdy wood would be dropped, milled, and lumbered to build the frames of 150 airplanes carrying Allied aviators above the Western Front.

The United States joined the Allied side of the Great War in 1917 during “Bloody April,” a month in which the Imperial German Army shot down five British aircraft for every German plane lost. After three years defending stagnant lines, the exhausted Allies felt relief. Besides sending an army, the Americans pledged that by early 1918 they would be delivering at least 2,000 expertly piloted airplanes a month.

Washington was nowhere near ready to make good on that promise. The country that 14 years earlier had been the scene of the world’s first powered human flight entered the first war of the air age with fewer than 300 military aircraft, not one of which was fit for battle. The U.S. Council of National Defense reasoned that America could catch up by repurposing a thriving automobile industry to build planes, an effort overseen by an Aircraft

Production Board. In July 1917, Congress allocated $640 million at the time, a record outlay for a single cause—to pay for the production of 23,000 planes within a year.

The Aircraft Board faced a steep climb as well as a technical challenge that General John J. Pershing, commander of the American Expeditionary Forces, spotted immediately. The frames and many components of the era’s airplanes were wooden, held together with wire and covered with linen. No timber better suited aircraft manufacture than Sitka spruce—strong, light, flexible, resilient, and sought after by luthiers, playground designers, and coffin makers. To meet Allied requirements, the United States would need to harvest 120 million board feet of spruce lumber in the coming year. However, the species’ only habitat, a 50-mile-wide sliver of the West Coast from the Canadian border into northern California, had been enmeshed for years in a labor dispute. Loggers and millworkers were demanding better hours and safer, healthier conditions. Lumber companies refused to go along. The notoriously radical Industrial Workers of the World had been fanning the flames, leading strikes and engaging in sabotage that in Washington state alone had shut down 75 percent of timber operations. This unrest, unchecked, might stall aircraft production, Pershing warned Secretary of War Newton Baker in May 1917. With Baker’s blessing, Pershing asked his chief of staff, General James Harbord, to choose a friend of the army to serve discreetly as an unofficial monitor of the Northwest labor situation while the AEF made ready for war. Harbord found the perfect man in a Michigan penitentiary.

Brice P. Disque, born in 1879 in California, Ohio, had joined the U.S. Volunteers at 19, in time to compile sterling enough

a record fighting Moro rebels in the Philippine-American War to earn a regular army commission as well as Pershing’s and Harbord’s respect. An accomplished horseman, Disque turned heads during peacetime as an instructor of National Guard cavalry units. He had led the once-notoriously derelict Michigan branch of the Guard to a national award for efficiency. Transferred to the U.S.-administered Philippines in 1915, Disque took command of a foundering 100-man unit responsible for maintaining wagons, tents, and other army assets too large to ship home for repairs. In six weeks, he increased the local labor pool 20-fold by offering ex-cons performance bonuses. Disque and his cadre quickly completed army repair jobs and began taking civilian contracts, making money for Uncle Sam fixing things.

Despite his managerial ingenuity, in the peacetime army Disque failed to advance beyond a captaincy, impelling him to resign in November 1916. He went to work in southern Michigan, running money-losing Jackson State Prison, the nation’s largest penitentiary. By the time the United States declared war, Disque had that facility’s 1,500 inmates operating a furniture factory, a granite quarry, a 5,000-acre farm, and a cannery. In 1917 these enterprises collectively netted the state $371,000. Hoping a combat command might revive his military career, Disque submitted an application for recommission that crossed Harbord’s desk.

At Pershing’s urging, Disque reluctantly agreed to stay on at Jackson, monitoring the Northwest labor strife from afar. All summer, Disque cabled his dismay to the War Department as civilian efforts failed to broker industrial peace in the Northwest. Even master labor negotiator Carleton Parker, successful subduer of Seattle shipyard walkouts and IWW-led farm strikes in California, could not bring the belligerents to accord. In August, mills in the Northwest produced less than two million board feet of spruce, only a fifth of the Aircraft Production Board’s 10 million board-foot quota.

In mid-September, Disque gladly accepted a commission as a lieutenant colonel, along with orders for the Western Front with General Benjamin Foulois’s tactical aviation unit. Arriving in Washington, DC, on October 1, uniforms pressed and rucksack ready, Disque was summoned to the War Department, where Baker asked him to trade his berth on Foulois’s ship for a transcontinental ticket in the opposite direction. The War Department badly needed Disque out west to hasten the flow of aircraft-grade spruce to factories back east.

Lacking domestic warplane designs, the Aircraft Board ordered Dayton-Wright, Curtiss, Fisher Body, Standard Aero, and other firms to build DeHavilland DH-4 bombers, designed by Britain’s Airco and licensed to American firms gratis. The United States did produce its own training aircraft. Curtiss hired a ringer from the British company Sopwith to design its JN-4 “Jenny,” and Standard Aero built its own Standard J-1 trainer, as did Dayton-Wright, Fisher Body, and Wright-Martin. At plants in Detroit, Michigan, Dayton, Ohio, and Buffalo, New York, aircraft were back-ordered. “Nothing less than a great national emergency could have persuaded me to undertake a duty in time of war six thousand miles from the battlefront,” Disque later wrote.

Arriving in Seattle on October 10, Disque joined Parker to tour three dozen dangerously undermanned logging camps and mills. A third of the camps had no toilets. Half lacked adequate bunks. The chow was swill. “We treated captured Moros better in the Philippines during a war,” noted

Disque, who politely declined more than one bowl of wretched stew.

On Disque’s ninth day in the Northwest, he and Parker proposed that the Signal Corps, of which the army’s fledgling aviation program was part, field a division of at least 7,000 soldiers to fill gaps in the civilian labor pool rent by strikes and the draft. The army’s presence seemed likely to raise living standards, neutralize the IWW, and rein in a 600 percent turnover rate among loggers and lumbermen, they reasoned.

With these plans in place, Disque hoped to join Foulois in France. But during his short time in the Northwest, the fair-haired, well-spoken soldier, rarely seen without a cigar between his teeth, had charmed workers and employers. The region’s press praised him as the long-awaited solution to labor gridlock. On November 3, the day German bullets and blades claimed the first three doughboys to fall in France, Disque secured permission to form the U.S. Army Spruce Production Division. He also sullenly agreed to lead it.

In early December, spruce soldiers began reporting to Vancouver Barracks, an army post that had stood on the Washington side of the Columbia River since 1849. Many men had transferred from engineering regiments. Only half had logging experience. Trainers recruited from among old-time lumbermen, along with University of Washington forestry professors, provided a primer on felling 50-ton trees without getting killed. Armed with basic knowledge of limbing, bucking—sawing into logs—and hauling, the first spruce squadrons were dispatched in late December to labor alongside civilian employees of logging companies inspired by government lumber contracts to upgrade camp conditions.

For the first wave of “sprucers,” mostly Easterners, the forests of Washington and Oregon were as foreign as Belleau Wood. The troops lived in the saltwater bogs where spruce thrived. Winter’s constant heavy rain penetrated the stoutest boot and tent. Save for wearing campaign hats, soldiers adopted the dress of local loggers: button-down wool shirts, suspenders, and paraffin-coated “tin pants” notoriously difficult to climb into but secure against water and jabs from jagged sticks. The lumbermen’s slang-ridden version of English—a product of their primitive, isolated lifestyle—might as well have been French. Loggers were “timber-beasts” who had been “fighting for their cakes” in the big woods for decades, felling “pay-poles” in return for “frog-skins.” They naturally distrusted well-kept outsiders they called “slick-soled punks.”

Lest civilian loggers complain that the army was hiring scabs, the spruce soldiers made the same wage as civilian counterparts—at least twice what a standard doughboy earned. Further blurring the line between civilian and military, Disque and Parker created the Loyal Legion of Loggers and Lumbermen. This unprecedented government-promoted labor organization sought to unite lumber industry executives and their employees with a mutual

commitment to defeating the Kaiser. “Every airplane we fail to build this winter is like torpedoing five transports full of American soldiers,” Legion recruiters warned prospects. By the end of January 1918, 35,000 civilian laborers in Washington and Oregon were sporting the Legion’s shiny round membership pin. Within a month, more than 150 employers had signed on, lured by the promise of priority in receiving government contracts and sprucers to fulfill them. The Legion authorized Disque to set hours and wages as needed for the duration. On March 1, he established an industrywide eight-hour workday, settling a decade-long dispute and virtually ending strikes. “Colonel Disque has proved himself to be a diplomat of the first order,” raved a Portland Oregonian editorial. “The government needs more such men to manage its war activities.”

This praise was music to weary ears in the other Washington. The auto-turned-aircraft industry was nowhere near meeting the government’s ambitious production schedule; in March American pilots would take to the skies at the controls of hand-me-down French Nieu-port fighters and Breguet bombers. “Secretary Baker is grateful,” a War Department official cabled Disque. “The rays of sunshine that you send him are the only bright spots he sees.”

Patriotic fervor had put a stable workforce in the woods but love of country alone could not pull logs out. Specimens of Sitka spruce, the world’s third largest tree, grew individually, widely dispersed among other species—one aircraft-grade spruce per three to four acres of forest. Before the war, the cost of building infrastructure for logging the big spruces had drawn lumbermen to stands of more numerous and accessible conifers like Douglas fir.

To meet Allied needs, Disque calculated, loggers had to move 70 million feet of logs—weighing roughly 192,000 tons—an average of 20 miles. The division planned to lay 350 miles of rail line to reach the trees once late spring, with its drier weather, arrived. Until then, unable to haul logs whole, government-contracted companies would fell trees and rive, or split, trunks where they landed, dragging only mill-worthy pieces—about one-sixth of each log—out of the forest. Notoriously wasteful and expensive, riving appalled commercial lumbermen. Disque was undeterred.

“To a soldier, in time of war, any means that are necessary are justifiable,” he later wrote. “I determined to ship the 10 million feet [per month] at the earliest possible date, regardless of cost, or of whom it hurt, because by so doing I might assist in stopping the war one day earlier.”

By March 1918, more than 60 saw and ax squadrons, averaging 200 soldiers each, were in the woods, wielding mauls and wedges beside civilian loggers who had come to value the soldiers’ involvement. “Big, husky, two-fisted fellows, young and with plenty of both muscle and brains, they fit into the woods as a springboard fits into its notch in a tree,” The Timberman, an Oregon monthly, wrote.

Aircraft construction standards stipulated that spruce lumber be knot-free and perfectly straight-grained. When the Spruce Production Division arrived at Vancouver Barracks only 10 percent of spruce boards from the region’s 37 commercial mills were making the grade. In only 45 days, 5,000 soldiers built a giant state-of-the-art mill on the barracks polo fields that promised to raise acceptability to 60 percent. On February 7, Disque’s wife, Mary Florence, threw a switch that powered up the new mill. In April the industry shipped 13.5 million board feet of lumber, exceeding the monthly Aircraft Board quota.

In spring 1918 Russia made a separate peace with the Central Powers, freeing 50 German infantry divisions to pivot west and intensifying Allied need for warplanes. Under the Aircraft Board’s direction, America’s inexperienced factories had concentrated on the DeHavilland DH-4. By the time the first American-made versions of the light two-seater biplane arrived in France in May, British and French manufacturers had moved on to heavier bombers and faster fighters that kept pace with battlefield needs. A frustrated War Department reorganized the aircraft program, creating the Bureau of Aircraft Production, which ordered U.S. airplane makers to try new designs. Meanwhile, the Bureau’s director, copper mogul John D. Ryan, enlarged the Spruce Production Division to nearly 30,000 soldiers and arranged to transition the organization from the military to a majority government-owned corporation that could more nimbly negotiate contracts and accept payments from Allied nations. Ryan pressed Disque to pick up speed so more lumber—including Douglas fir and Port Orford cedar, now approved for certain aerial uses—could be shipped to factories in France and Britain now fielding the powerful SPAD S.VII, the quick-climbing Sopwith Snipe, the agile Bristol Fighter, and the speedy S.E.5.

The colonel did his best. When rainy season ended, Division engineers began laying railroad track that by fall would open access to 12.5 billion feet of timber. Selective logging of whole trees replaced riving. Disque got permission to sell lumber unsuitable for aircraft to wood-hungry makers of railcars, farm equipment, and furniture, recouping much of the cost of building the Vancouver Barracks mill. He persuaded federal railroad administrators to make aircraft lumber priority cargo, cutting the average time to ship a flatcar of wood to eastern factories and Atlantic ports from 50 days to 10.

By late summer, Disque had 22,000 soldiers and 85,000 Loyal Legion members on the job. The work was grueling, but most of these woodsmen were enjoying relatively modern facilities and benefitting from higher safety standards. Accidents, whether industrial or, as once occurred, when a hunter mistook a khaki-clad logger for a deer, caused injuries and deaths, but the incidence was nowhere near pre-war levels. IWW activity had all but ceased and logger and millworker turnover were down to 40 percent.

The Legion worked tirelessly on morale. Chaplains, musicians, athletic trainers, librarians, and motion picture projectionists circulated among the camps. Exhortative documentaries like “Tree to Trench” followed Northwest lumber through the Dayton-Wright airplane factory in Ohio and into the skies above France and Belgium. Occasionally foreign diplomats and soldiers home from combat visited, applauding the sprucers for their hand in the war effort. The men appreciated testimonials, but also felt forlorn. “I have seen many brave men of mature years shed tears of regret when advised that they could not be transferred to a combatant division,” Disque wrote.

Late July 1918 brought hope. Aircraft Production Director Ryan traveled west, challenging the industry to boost output to 30 million board feet monthly. During Ryan’s visit, Division officers threw Disque a surprise birthday party, concluding with a prayer that the mortified colonel receive a brigadier general’s star. Before returning east, Ryan quietly assured Disque that that wish would be granted and proclaimed to a crowd at Vancouver Barracks that as soon as the Division completed work on a pair of new mills planned for Port Angeles, Washington, and Yaquina Bay, Oregon, Disque would organize loggers as a combat regiment. Ten thousand men went “wild with joy,” their commander recalled later.

It was not to be. Disque was promoted on October 1 and that month oversaw the division’s seamless shift to civilian status as the Spruce Production Corporation. However, Brigadier General Disque arrived at the War Department in Washington on November 11, bearing an update on the nearly complete mills, in time to hear of Germany’s surrender that day. The next day, he telegraphed orders to all 234 camps to cease logging and construction.

The thunder of falling behemoths gave way to the subdued sounds of 1,214 officers and 27,520 enlisted sprucers tidying camps and mills. By February, the troops had demobilized and the 125,000 members of the Loyal Legion, now working at sites as far east as Montana, had transformed their organization into a civilian union. Commercial loggers resumed their casual pursuit of spruce to meet demands of piano, guitar, and furniture makers, soon to be joined by paper mills that coveted long-fibered spruce wood for pulp.

Disque resigned from active duty in March 1919, certain that his lack of a combat command precluded a meaningful military career, but proud to have produced a staggering 141 million board feet of select lumber in 12 months. “Our part has been carried out far from the battlefront with no chance for distinguished service in combat,” he told his men in one of his final holiday messages. “But let every man remember always that without the airplane lumber, which we, practically alone, have furnished for the entire Allied cause, this day of Thanksgiving could not have been.”

The sprucers’ triumph was buried by the abysmal record of the U.S. aircraft production program. Pilots dubbed the 1,200 DH-4s that reached the front “flaming coffins” for their tendency to combust spontaneously. The planes saw minimal use and the war ended before improved models and new designs Ryan had ordered arrived in France. Instead, American aviators had earned reputations for skill and valor in 5,000 planes borrowed or purchased from other Allied forces. “We had to take what was given to us,” lamented leading American ace Captain Eddie Rickenbacker. “We felt that we were not fulfilling the expectations of the people back home, who had been told that we had 20,000 of the best aeroplanes in the world, and all made in America.” In 1919, Congress investigated the aircraft industry. An astounded

Disque spent months defending his operation against accusations of overspending. He defused charges by proving that by the time the government sold off rail lines, equipment, and excess lumber, the spruce effort had cost the United States less than one day of hostilities in Europe—and 68.9 percent of the warplane-grade lumber harvested by the division had gone to Allied nations that did build and field combat-worthy aircraft.

Aided by Parker and others, Disque had tamed industrial chaos into a finely tuned machine and fathered the Loyal Legion of Lumbermen, which as a labor organization would lead the region’s largest industry well into the 1930s. In peacetime Brice P. Disque faded from the headlines into life as a business consultant, often working for friends from his spruce days, until his death in New York in 1960.