The Allied accomplishment on D-Day was made possible by years of intelligence success that would continue until ultimate victory in Normandy. During the campaign for France, the Allies had success in a number of key intelligence efforts. These included Ultra, the interception and decryption of high-level German radio communications. Deception efforts, most notably Operation Fortitude, misled German intelligence as to the time and place of Allied invasions of the Continent. But perhaps the most cloak-and-dagger of those operations was the Allied effort to mislead German human intelligence (HUMINT) through the use of double agents. These were spies in Britain that the Germans valued, trusted and relied upon for strategic warning. The problem from the German standpoint was that they were all, without exception, working for British intelligence. Of all the stories surrounding those agents, none was as dramatic — or as funny — as that of ‘Garbo,’ the code name of Juan Pujol Garcia, double agent.

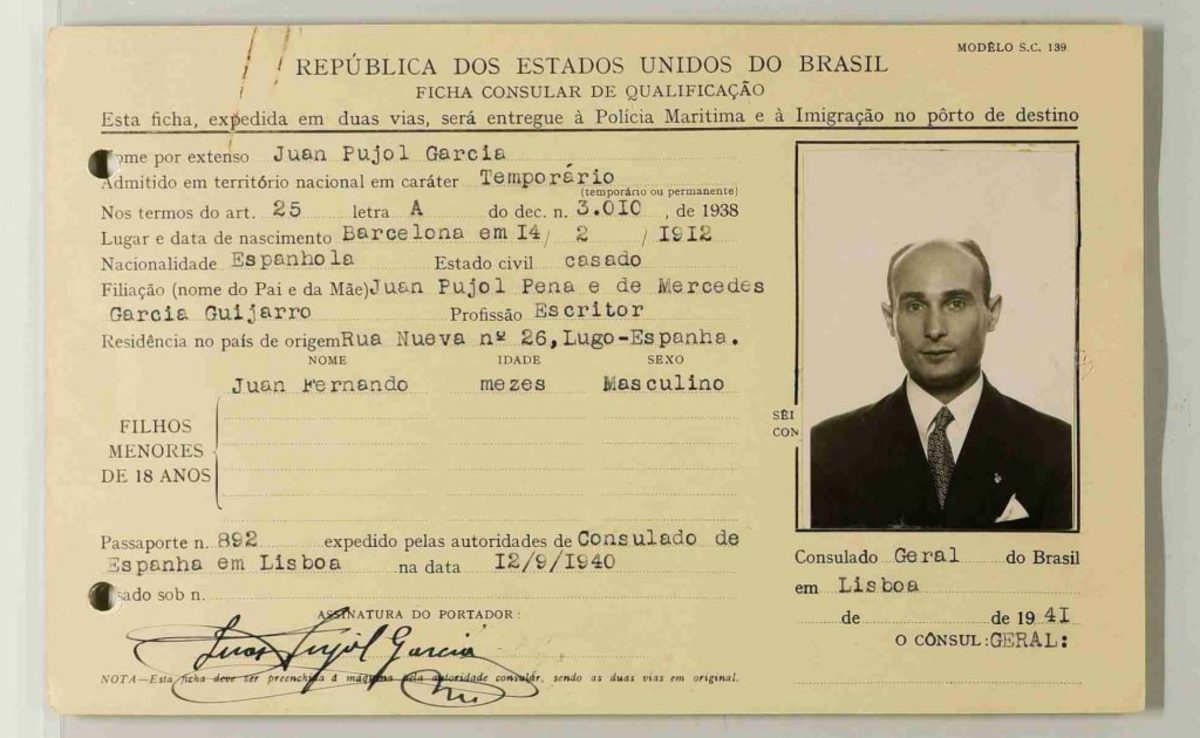

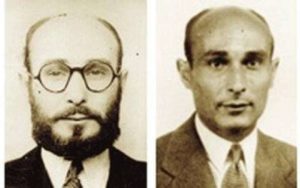

Pujol, from Barcelona, was a Nationalist veteran of the Spanish Civil War. Anti-Communist and anti-Nazi, in January 1941 he decided to volunteer as a British spy, but failed to make contact with an appropriate official in the Madrid embassy. Pujol then decided that he would be more useful to British intelligence if he were already a German agent. Following a trip to Portugal, he persuaded Gustave Knittel, a Madrid-based agent of Germany’s Abwehr intelligence service, code-named ‘Frederico,’ that he had a visa for England and would be able to spy there for Germany. Pujol became Abwehr agent Arabel, with invisible ink, secret codes and 600 pounds for expenses.

The catch was that the visa was a forgery. Pujol could travel no closer to Britain than Lisbon. So, starting in October 1941, he started supplying the Abwehr with in-depth reports on Britain that he researched at the Lisbon public library. He invented a network of three sub-agents and made up cloak-and-dagger escapes for himself and them for his Abwehr superiors. Some of his reports from Lisbon were hilarious. He made imaginary trips throughout Britain and warned that ‘there are in Glasgow men who will do anything for a liter of wine.’ But the Abwehr was impressed with the ‘accuracy’ of the material he supplied. Indeed, some of his imaginary reports — such as that of convoys’ sailings — were so close to the mark that when the British learned of them through Ultra decrypts, their counterintelligence service MI6 launched a full-scale spy hunt in Britain.

In February 1942, Pujol tried again to contact the Allies. This time, U.S. Navy Lieutenant Patrick Demorest in the naval attach’s office in Lisbon recognized Pujol’s potential value. He called in his British counterparts, and within a few months Pujol was actually in England, undergoing a thorough MI5 debriefing to make sure he was genuine. He was accepted by British MI5 as agent Garbo, one of many German spies being operated by the British under what came to be known as the double-cross system.

By 1944 Garbo was part of the cover plan for Operation Overlord. Prepared by Supreme Headquarters Allied Expeditionary Force (SHAEF) and implemented by the London Controlling Section, the plan included Operation Fortitude and diversionary operations. By this time, Garbo — as Arabel — had told his controllers that he ran a network of 24 spies in Britain. The regular reports of Garbo’s subagents and their sources were all written by British intelligence to aid the Overlord cover plan. They were sent by radio, or deposited in a bank safe-deposit box in Lisbon by Garbo’s trusted courier, in reality a British agent. When one of the fictitious spies ‘died of natural causes,’ British intelligence arranged for an obituary to appear in the press, where the Abwehr was sure to notice it.

Garbo’s agents provided the Abwehr with lots of information about Allied preparations for an invasion of Norway. These found a receptive audience. Word of the bogus Norwegian invasion was timed to coincide with increased British naval activity against Norway. Consequently, German forces in Norway increased from nine to 12 divisions by mid-May. As with D-Day itself, the reasons for this cannot be easily broken down and credited, but the double agents certainly contributed to the overall German strategic myopia.

Immediately before D-Day, Garbo had his German contacts stand by for an urgent radio message, which kept them from being available for other tasks. This was followed, in the early hours of D-Day, with the news that the invasion was taking place in Normandy — confirming what the Germans were already starting to learn from their own service land-line reports. Garbo followed this, later on June 6, with information that Overlord was only the first of several invasions to be launched against occupied Europe and that the invasion was a diversionary effort.

This increased his credibility with the Abwehr, and a longer message from Garbo on June 9, when decrypted, was rushed directly to Adolf Hitler. With reports that Normandy was a diversion, Hitler delayed the movement of German reserve divisions to the invasion battlefront. It was, in retrospect, Garbo’s biggest hit.

Garbo provided reports on bogus Allied invasion plans and the results of German V-1 and V-2 attacks on London throughout the summer. On July 29 he was awarded — via radio — the Iron Cross First Class, normally reserved for frontline fighting men. It showed the importance the Germans put on the information Garbo had supplied as part of the D-Day deception. The Germans still believed there would be another Allied invasion of France up until the invasion of southern France in mid-August.

Garbo continued to supply the Germans with misleading information until the end of the war. He survived to publish his memoirs in the 1980s, one of history’s most successful players of the most dangerous intelligence game ever.

Garbo was not the only D-Day double agent. Others, code-named ‘Brutus,’ ‘Mutt,’ ‘Freak,’ ‘Tricycle,’ ‘Treasure’ and ‘Tate,’ were also part of the deception campaign, though none achieved the same stature in German eyes as Garbo. Fortunately, the Allies had the time, resources and planning to make sure that their reports were part of an integrated deception plan. The limitations placed on both the double-cross system and Ultra intelligence meant that specific reports could not be evaluated through the decrypts. When the Germans were able to obtain independent confirmation of the double agents’ reports, they usually checked out, because the Allies had moved troops or positioned dummy units or sailed a decoy convoy where the report disclosed. At great personal risk, Garbo and the other double agents made a significant contribution to the Allied D-Day success.

This article was written by David C. Isby and originally appeared in the June 2004 issue of World War II. For more great articles be sure to pick up your copy of World War II.