When Theodore White wrote The Making of the President, 1960, only 16 states held primaries, and he reported on only two—Wisconsin and West Virginia. Now the drill seems endless: photo ops on Iowa farms, town meetings in New Hampshire, speeches in three Southern states in one day. Several years ago, Barack Obama and Hillary Clinton scrambled for votes in Puerto Rico and Guam.

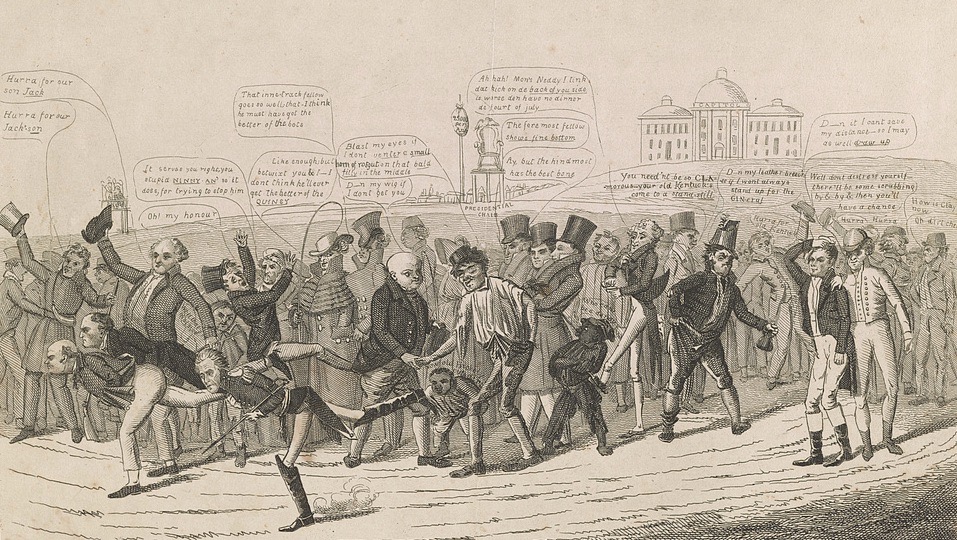

The nominating process has changed over the centuries, from congressional caucuses to party conventions to the marathon we have now. But it has always been arduous. The longest campaign in American history, and one of the bitterest, was for the election of 1824, and it lasted eight years.

James Monroe, who took the oath of office in March 1817, was clearly the end of a line of stand-up heroes from the Revolution. He had even been wounded at the Battle of Trenton. He was also the fourth president from Virginia, reflecting the state’s eminence. But times were changing. New York and Pennsylvania were catching up to the Old Dominion in population. The next presidential race would attract strong candidates from many states.

One aspect of the race was unique. The two-party system had broken down. The Federalists, the party of Alexander Hamilton and John Adams, had been disgraced by opposition to the War of 1812. In the election of 1816, Federalists carried only three out of 19 states, and would never mount another national campaign. Everyone who aspired to fill Monroe’s shoes belonged to the same party as Monroe—the first Republican Party, soon to rename itself the Democrats.

Three would-be presidents ran as insiders. The leader of the pack was Treasury Secretary William Crawford of Georgia. Crawford, just 45 years old in 1817, had a varied résumé— senator, diplomat and secretary of war. He was literally a fighter, having killed a political rival in a duel, then been wounded in a second duel by an ally of the dead man. Crawford’s supporters had pushed him for the Republican presidential nomination in 1816, but he never declared his candidacy, figuring he could wait out the Monroe years.

John Quincy Adams of Massachusetts, 50 years old, had better credentials—secretary of state, a traditional stepping stone to the White House, and the son of John Adams. But he was also a party jumper, first a Federalist, like his father, until 1808. Adams professed to be above politicking, but he kept a diary, observant and malicious, in which he monitored all the maneuvers of his rivals.

John Calhoun of South Carolina was only 35, helped by a powerful intellect and a fierce nationalism. After six years in Congress, he was tapped by Monroe to be secretary of war.

There were two outsiders in the field. Henry Clay of Kentucky, age 40, had been speaker of the House on and off since 1811. He was idealistic, eloquent and charming, and his strategy for winning the White House was to snipe at the administration.

Furthest outside was General Andrew Jackson, the same age as Adams. Jackson had been a Tennessee planter and politician for 20 years, but he was best known for his military exploits—crushing the Creek Indians during the War of 1812, and beating the British at the Battle of New Orleans. No one knew what his game plan was, but they knew it would be dramatic. Both Clay and Jackson had fought duels. Like Crawford, Jackson had killed his man.

There were few ideological differences among the candidates. All shared the post–War of 1812 consensus, known as the Era of Good Feeling, which embraced populist politics and a moderately activist government that could build national roads and levy protective tariffs. Each man struggled to find particular issues that would boost his chances.

Clay called for the United States to sympathize with rebels in South America and Greece who were throwing off Spanish and Turkish rule; Adams insisted on a more cautious foreign policy. Jackson caused a foreign policy stir of his own when he invaded Spanish Florida in 1818, in hot pursuit of Seminole Indian raiders, then hanged two British subjects he thought had stirred them up. Calhoun and Clay accused Jackson of acting without orders; Adams defended him. Crawford used the patronage powers of the Treasury Department—he could pick customs officers—to cement his position. Adams compared him to a parasitic worm in the administration’s body.

Because Monroe ran unopposed for reelection in 1820, jockeying among hopefuls went on for two full presidential terms. Tempers frayed. During one White House meeting late in the home stretch, Monroe refused to approve some of Crawford’s customs appointments. Crawford raised his cane and called the president a “damned infernal old scoundrel!” Monroe grabbed the fireplace tongs and threatened to have the treasury secretary thrown out. Crawford calmed down, but he and Monroe never met again.

The long race to succeed Monroe was decided by bedrock political realities. Inexperience hurt. Calhoun, the youngster of the group, decided in 1823 to run for vice president instead. He won it twice, becoming the second, and last, man to serve as a vice president under two presidents. Time and chance, as Ecclesiastes put it, played a dramatic role. In 1823 Crawford suffered a stroke after a doctor gave him the wrong medicine for a skin infection. Though he finally recovered, he went into seclusion, paralyzed and speechless, for weeks, blasting his front-runner status.

In the end, victory went to the best retail politician, who turned out, surprisingly, to be Adams. Once the states and people voted in 1824, Jackson had 99 electoral votes, Adams 84, Crawford 41, and Clay 37. No man had a majority, so the three top finishers went before the House, where the states voting as units picked the winner. Clay, in fourth place, was out of the running, but as the most powerful man in the House he became the kingmaker. Adams’ diary falls uncharacteristically silent at this point, but it is not hard to figure out what happened. Clay pushed enough Midwestern and Southern states into Adams’ column that, with his New England base, Adams (13 states) topped Jackson (7) and Crawford (4) on the first ballot. President Adams then tapped Clay to be his secretary of state. Jackson called it a corrupt bargain; it could equally be called coalition building.

The framers of the Constitution did not envision endless presidential campaigns. They knew that George Washington would be the first president, and they seem to have expected that after he died or retired the Electoral College and the House would act as gentlemanly deliberative bodies to pick the best man. It hasn’t worked that way. Sometimes the best man does win, but every politician thinks he is the best man. So every election cycle is too long and too hard-fought.