‘Watson set out to wring secrets from the Me-262. The swept wings, originally intended to adjust the center of gravity, turned out to be an elegant design feature for aircraft flying at near-supersonic speeds’

Late in World II, Lieutenant Robert Anspach was flying cover in his P-47 Thunderbolt for a group of B-26 Marauders near the Messerschmitt factory airfield at Lechfeld, Germany. From out of nowhere an enemy airplane suddenly rocketed past, blasting off a few rounds. It looked like nothing the Americans had seen before. Ever.

Wow, thought Anspach.

“Would you look at him!” one pilot exclaimed over the radio.

“Let’s go get him,” another said.

By that time, he was gone. That was Anspach’s introduction to the Me-262.

Same time, same theater: Lieutenant Robert Strobell, another P-47 driver, was ordered by a flamboyant colonel—white scarf, shiny brown leather jacket, a real Steve Canyon type—to fly a damaged B-17 with him from France to England. The trip was somewhat harrowing, though they managed to walk away from the landing. He was unimpressed by the colonel, thinking him arrogant.

And that was Strobell’s introduction to Colonel Harold Watson.

Something about Strobell must have impressed Watson, though. The next time Strobell saw him, the war in Europe was over, but the scarf was still wrapped around Watson’s neck. He barged importantly into Strobell’s office and tossed papers onto his desk. “This is all we know about the Me-262,” he barked. “I want you to draw field gear and go to Lechfeld, Germany. I want you to train pilots to fly it and crew chiefs to maintain it.” He’d already arranged for German mechanics and test pilots to help out. Watson spun around and left.

Hey, wait a minute, Strobell thought. The next day he was in a C-47 flying to Lechfeld.

It was said that Colonel Watson was Milton Caniff’s model for comic book hero Steve Canyon, and Watson did nothing to discourage the talk. An engineer and director of maintenance for the Ninth Air Force Service Command, Watson had just been put in charge of Operation Lusty (an acronym for Luftwaffe secret technology). Before the war, the U.S. didn’t have much hard information on enemy aircraft, but clearly Theirs were better than Ours. The primary Japanese fighter, the Mitsubishi A6M Zero, flew faster, higher and could turn circles inside contemporary Allied fighters such as the Grumman F4F Wildcat, Curtiss P-40 Warhawk and Hawker Hurricane. In most respects, the same held true for Germany’s Messerschmitt Bf-109.

As the war ground on, the Allies designed better fighters such as the Republic P-47 and North American P-51, which could fly higher, faster and were more heavily armed and armored than the Zero and 109. Yet while the Allies pounded Germany into submission, Nazi engineers kept cranking out advanced technology. Only a lack of fuel due to the constant, costly bombing of oil fields and refineries kept them on the ground.

The U.S. War Department opened the Air Technical Intelligence office, which, under Operation Lusty, issued “black lists” of enemy equipment it wanted to study. The lists were divided into piston-powered aircraft and jets. Watson placed the piston airplane roundup in the capable hands of Captain Fred McIntosh, but the jets generated the most excitement. On the black list: the Arado Ar-234, a hotdog-shaped twin-engine jet bomber; the tiny plywood Heinkel He-162 fighter, resembling a gecko with wings; and the Messerschmitt Me-163 rocket plane. Other Nazi weapons reflected a more desperate approach: a manned version of the V-1 buzz bomb, and a plywood rocket plane, the Bachem Ba-349 Natter, which took off vertically and carried 24 anti-aircraft rockets in its nose.

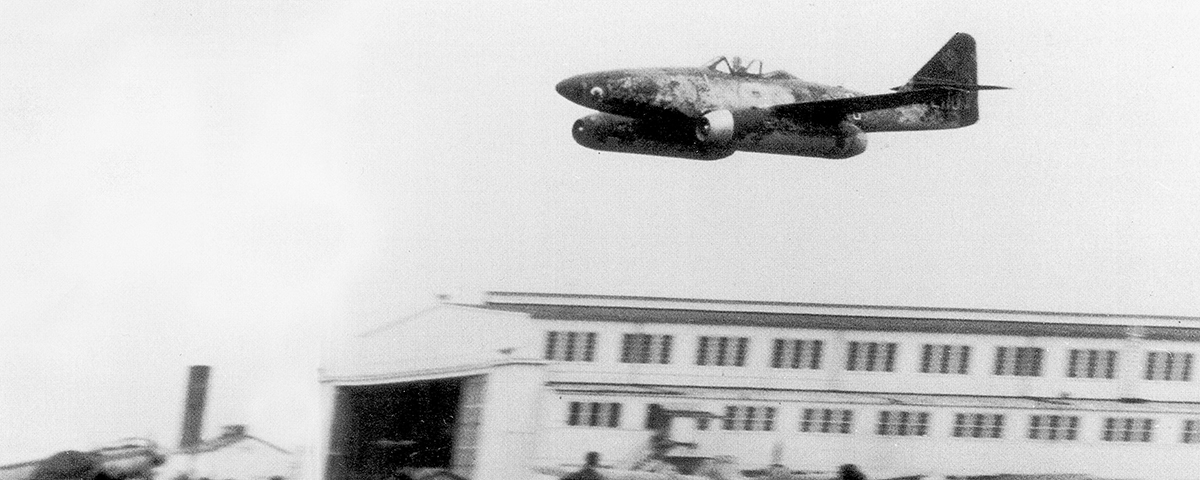

Of them all, the most important was the Me-262. The airplane that had startled Anspach was the pinnacle of the six-year-old jet age and the apex of Reich technology. A study in grace and power, it could fly at 540 mph, 100 mph faster than the P-51, yet it was only marginally larger: Its wing measured nearly 41 feet and its triangular-section fuselage stretched almost 35 feet—4 feet more wingspan and a fuselage 3 feet longer than the Mustang’s. Its boomerang-shaped wings were swept back not out of aerodynamics considerations, but to balance the plane on its nosewheel; the prototype sat on a tailwheel, and when lit the engines toasted and stripped the turf. The pod slung beneath each wing held a Junkers Jumo 004B jet engine that generated 1,980 pounds of thrust. In contrast, the experimental straight-wing Bell P-59, test-flying at California’s Muroc Army Airfield, could, even with two 2,000-pound-thrust GE engines, only hit 413 mph. Most 262s were clustered around Lechfeld, near the Messerschmitt factory runway.

One week after receiving orders from Watson, and less than three weeks after the German surrender, Strobell landed at that airfield and fell asleep alone on the floor of a shot-up barracks littered with glass, gripping a .45, after tying a string of cans across the building’s entrance. The next morning he got his first close-up look at the Me-262s strewn around the field and hidden among the trees. German troops had damaged some on the way out, while Allied troops damaged others on the way in. Some lacked instruments and other parts that had been liberated by people roaming the countryside looking to salvage anything they could trade for a meal. Some had engines and some didn’t; a few had a five-pound block of TNT strapped beneath the seat—a fine how-do-you-do for any pilot. The black list called for 15 in flying condition. Strobell scraped together 30-odd airplanes, from which to resurrect the 15.

With the war finished in Europe, Lieutenant Anspach and the rest of the remaining Ninth Air Force pilots waited around for an assignment—anything besides wondering whether they’d be sent to the Pacific. Some had already accumulated enough points to be discharged through the military’s new point system. (Soldiers received points for each month in the service, each month overseas, each combat mission flown, wounds, medals, you name it.)

Anspach heard that intelligence wanted pilots to test-fly captured aircraft. No other details emerged, except that the pilots who got the assignment would be sent home quicker. He and Captain Fred Hillis were interviewed and picked. Same for Lieutenant Roy Brown, who was young, craved action and liked the secret detail because it sounded like it involved lots of flying time. Three other pilots made the cut: Captain Kenneth Dahlstrom and Lieutenants William Haynes and James K. “Ken” Holt. All flew to Lechfeld except Haynes, who joined them later. They formed the core of the 54th Air Disarmament Squadron, with Strobell in command. In addition to the pilots there were 10 American crew chiefs and 28 German mechanics.

Days after their arrival, Watson himself landed and briefed the pilots. They were to fulfill the black list, then fly the rebuilt airplanes to Cherbourg, France, where the 262s would be loaded onto an aircraft carrier and shipped Stateside for a further shakedown. Watson had already gathered the Messerschmitt factory mechanics who’d worked on the jets, and chose six Messerschmitt test pilots to instruct the Americans. Among them: Ludwig “Willie” Huffman, who before the war had set several world glider records, and Karl Baur, Messerschmitt’s chief test pilot, who knew more about the 262 than anyone alive, and more than he would confess to any Americans. Accustomed to privilege during the Reich, he now only spoke when spoken to. The pilots nicknamed him “Pete.”

While Watson lectured, Anspach felt inspired: The colonel was obviously a sharp cookie, and Anspach thought they were getting a good deal. To Strobell, who knew him better, Watson seemed self-absorbed, egotistical—but he was also a mover and a shaker. In fact, he moved on right after the speech.

By early June the mechanics rolled the first rebuilt 262 onto the runway. Strobell ordered Pete to fly the airplane: If the Germans wanted to sabotage one of their ships, they’d be killing one of their finest test pilots. Strobell told the ground crew to fill the tanks halfway, and had Pete strap into the cockpit. Pete lifted off, stayed within sight of the field and then set down gently—just as Strobell had ordered. After the fighter rolled to a stop, Strobell slid into Pete’s place and taxied back to the hangar, where an American crew serviced the machine. Strobell then taxied to the business end of the runway, held the brakes, shoved the throttles forward and let go.

He made three pilot errors. First, he lifted the nose too soon, which prevented the airplane from taking off. Realizing it, he lowered the nose to build speed, and lifted off with millimeters of runway to spare. The jet shot through 200, 300, 400 feet. Out of the corner of his eye, he saw slats flapping on the wing. The 262 didn’t have a radio, so Strobell was unable to call and see if it was a problem—but the airplane rocketed ever faster and the slats stayed closed. Once he had the landing gear up, he forgot all about it. Glancing out of the cockpit again, Strobell for the first time understood how fast this jet flew. Like greased lightning. Unadulterated speed. The future.

Sticking close to the field, he checked over the instruments, then turned to line up with the runway. He came in too fast to lower the gear and still keep them bolted on. Even pulling power off didn’t slow it down: The 262 had no spinning prop blades to help brake it. So he overshot the runway—pilot error number two. Strobell banked the jet around and flew back up the runway, pulling up on the nose to bleed off enough speed to lower the gear. When he hit the right speed, and the gear started coming down, the 262 popped up and the altimeter hit 2,500 feet. Pilot error number three. The nose-gear door, a rectangle of aluminum, doubled as an airbrake. With the gear finally down and locked, he made a smooth landing. Not even hot. Right where he wanted to touch down.

Like everyone in the Army Air Forces, Strobell wore a collar insignia, a pair of gold wings with a silver prop. After he shut down the 262 and jumped off the wing, Anspach and Holt snapped off the collar insignia’s props. “You don’t need these,” Anspach said.

Later, though, after the exhilaration wore off, Strobell got to thinking, Why didn’t the German pilots tell me about the slats, and how to kill the speed and about the nose pointing up? Either they were trying to kill him, or maybe because the Germans were test pilots, all the stuff that scared the hell out of him would have been routine to them. Once he had observed the Germans for a while, he started believing they were loyal to Messerschmitt, not the Third Reich. In fact, only one was a former Luftwaffe pilot. He showed up several days late in full uniform, driving a red sports car with his girlfriend by his side. Disgusted, Strobell told him to leave. The other Germans took pride in their airplane and craftsmanship. They were elated that, despite the war’s destruction, they had built a transcendent machine, and that the technology they had helped develop might live on.

Gradually relations eased between the Americans and Germans. The Germans revived more jets; the Americans paid them and supplied their families with K-rations. One American, Eugene Freiburger, occasionally went hunting and shot Rehbucks, tiny deer indigenous to Bavaria, handing over part of his kill to the families.

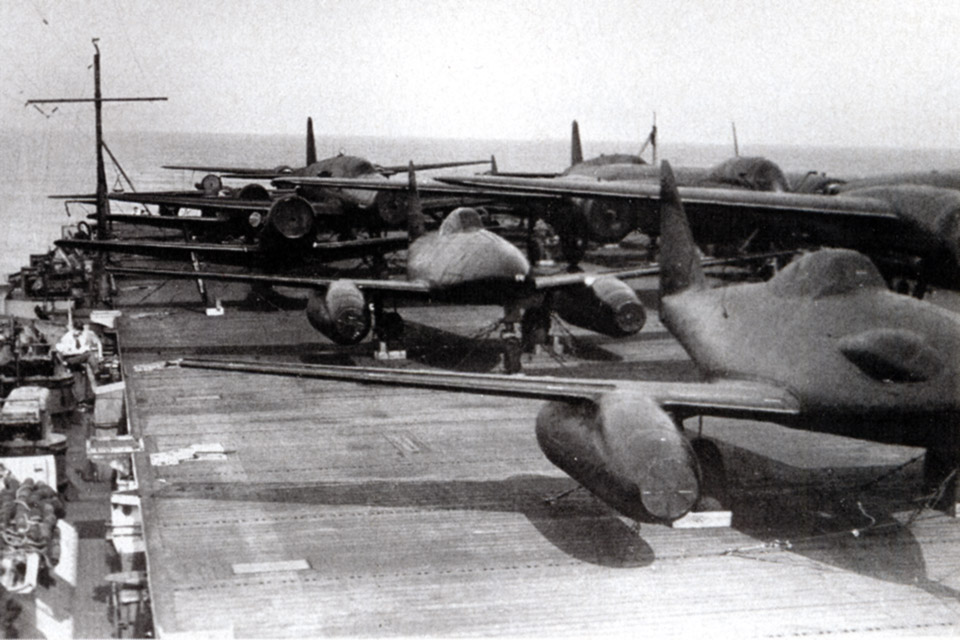

Out of the 30-plus Me-262s, the mechanics could bolt together only 10 in airworthy condition. As they pushed all 10 onto the flight line, swastikas and crosses spray-painted over with U.S. star insignia, the American pilots started getting checked out in them. They familiarized themselves with the cockpit layout and German instruments. Strobell told them about the 262’s flight characteristics: no torque from spinning props, no slowing down when the power was pulled back—and speed in massive quantities. They practiced firing up the Jumos on a damaged 262 that a mechanic chained to the ground. Then each in turn strapped into the pilot’s seat of an Me-262B with Baur, flew a quick lap around the field and landed. Each time, someone would be there to break the prop blades off his collar insignia. When Watson flew in for a progress report, he saw the defaced insignia and didn’t disapprove; in fact, he was said to be pretty proud of them for doing it.

The Jumo engines ran only a few hours before they needed to be rebuilt, so Watson ordered his team to collect enough spare parts for the jets. The German mechanics had concealed several new engines in a barn. Once they had loaded the engines into trucks, along with enough spares to keep them running, Watson also ordered Strobell to round up the mechanics’ tools before the Americans pulled out. The Messerschmitt men’s metric tools were practically all they had left after six years of war. In America we have the capability to fabricate anything, Strobell thought. But these tools are their livelihood. No way am I going to take a man’s livelihood away. When the trucks pulled out for the trip to Cherbourg, he left the tools behind.

The pilots followed on June 10. For the first leg of the trip they flew to Melun, France, 365 miles away. None of the Americans had flown more than 30 minutes in the 262, and none save Strobell had logged solo time. After Brown took off, he thought the airplane was easy—a pleasure, even—to fly: The controls were responsive, there were no vibrations and compared to a piston-engine fighter it whispered. It also flew much faster than the fastest plane he’d ever piloted; he shuffled through his navigation charts one right after the other. Watson had a rougher time: Burning too much fuel, he made a forced landing at St. Dizier. Before he could take off again, a crew had to chop down trees at the runway’s end.

Once the pilots all gathered at Melun, they waited. The days dragged on, then Strobell learned that Watson wanted to demonstrate the 262 for General Carl Spaatz, chief of the Army Air Forces in Europe. When the general finally showed up, the men all wore new shoulder patches sewn on their uniforms: Donald Duck circling the globe on a jet engine, with “Watson’s Whizzers” in print. Anspach came up with the name. Strobell, Holt and Hillis demonstrated the 262 with three or four fast passes, plus some mild maneuvers—but at the end Strobell couldn’t resist performing a vertical barrel roll. “Hal,” Spaatz said to Watson, “that’s a wicked airplane. Wicked. WICKED! I’m sure glad they [Germany] screwed up the tactical use…”

Messerschmitt had originally designed the Me-262 as an interceptor capable of wreaking havoc on Allied bomber formations. Although the jets were ready to fulfill that role by November 1943, Adolf Hitler instead demanded they be converted to bombers for tactical hit-and-run strikes. When the 262 entered combat in July 1944, it did so in both roles, though the fighter-bombers were soon forced to join the interceptors in a desperate bid to stem the tide of Allied bombers.

The ferrying flight began to unravel on the trip’s final leg, Melun to Cherbourg. The 262s carried no navigational instruments, so when Anspach encountered overcast near Cherbourg he ascended, then descended where he thought the airport should be—to find he was skimming over the English Channel. The jet was on fumes when he spotted the Isle of Jersey. The sight of a German jet touching down sent the local troops on full alert. “Who are you? Where did you come from?” they demanded. Anspach explained. During refueling, a soldier told him that the jet’s main gear had barely cleared the church steeple as he came in to land.

Of the 10 Me-262s the mechanics had pieced together, Colonel Watson took a shine to one with a long-bore 50mm cannon protruding from its nose. At Melun he christened it Happy Hunter II after his son Hunter. Strobell chose the most experienced pilot to fly it, Willie Huffman. Halfway to Cherbourg, a turbine failed, the jet shuddered violently and plunged. Huffman shut down the other engine, pulled the nose back, unbuckled his seatbelt and popped open the canopy—simultaneously. He rolled the jet on its back, and it bucked him out. They found him near the smoking crater, a bloody mess, but alive.

The brass suspected that Huffman had deliberately crashed the jet, and Strobell heard he was to be court-martialed for assigning a German to fly it. But when they examined the wreckage, they found the engine had shed turbine blades. Still, the whole incident left a bad taste in Strobell’s mouth, in no small part due to Watson’s failure to stick up for him.

To retrieve some gear, Strobell had to fly to Manheim, Germany. The only available airplane was a P-47 classified as “war weary.” Moments after he took off, the Thunderbolt exploded, blowing Strobell high enough for his parachute to open. He spent 45 days in a hospital recovering from burns, and all his records from Lechfeld, plus some 20 rolls of film, were torched in the crash.

The other Luftwaffe aircraft landed in Cherbourg, where they were loaded aboard the British escort carrier HMS Reaper for the trip across the Atlantic to Newark, N.J. They were then flown when possible, or trucked when not, to test facilities. Anspach and Holt ferried some. During a landing in Pittsburgh, Holt’s brakes failed. Spying a cornfield at the other end of the runway, he figured that would stop him, but he didn’t count on a 30-foot drop-off at the runway’s end. The 262 rolled off and smacked the ground flat, snapping the airplane in half just behind the cockpit. Holt couldn’t remember scrambling out, but he recalled seeing the 262 burning.

Strobell was assigned to Freeman Field in Indiana to compile an Me-262 checklist for U.S. pilots. Air Technical Intelligence and Watson set out to wring secrets from the jets. The swept wings, originally intended to adjust the center of gravity, turned out to be an elegant design feature for aircraft flying at near-supersonic speeds. Air piles up against a straight wing but slides off a swept one—one problem slowing down the P-59, America’s first jet fighter. The P-59 also used an inferior engine; the German Jumo offered slicker performance. All engineers needed to do was copy it. Pilots flew the 262s at airshows to illustrate the military’s need for jet fighters.

As for the Americans who rebuilt and flew them, most scraped together enough points for a discharge. And with that the original crew of the 54th Air Disarmament Squadron, the Army Air Forces’ first jet fighter squadron—Watson’s Whizzers—quietly faded away.

Phil Scott is the author of The Shoulders of Giants: A History of Human Flight to 1919. For further reading, he recommends Watson’s Whizzers: Operation Lusty and the Race for Nazi Aviation Technology, by Wolfgang W.E. Samuel. Also see the Watson’s Whizzers online history at www.stormbirds.com.