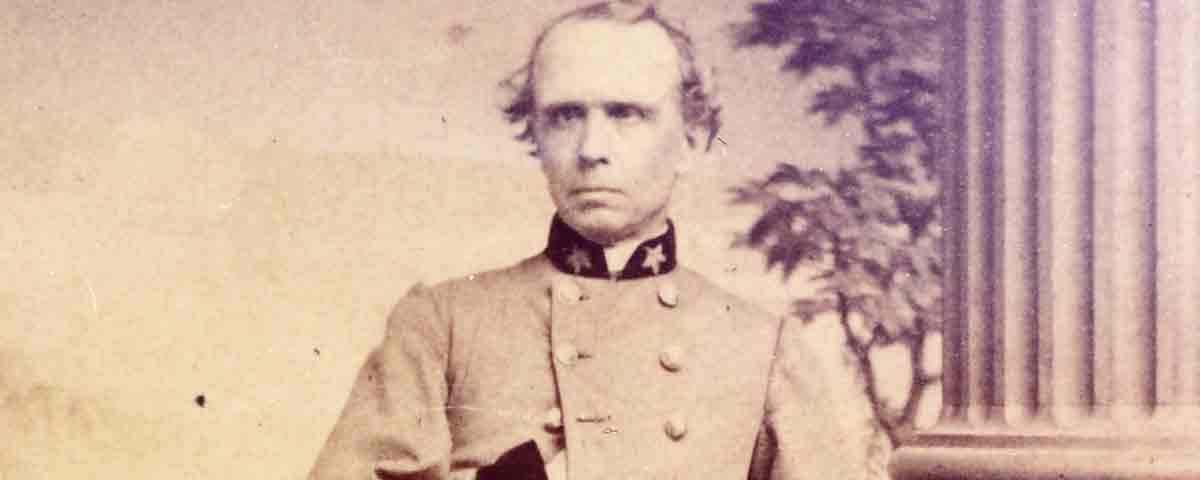

A Confederate Surgeon kept his faith in his cause during the war’s last days

[dropcap]D[/dropcap]r. Francis Marion Robertson was a prominent figure in Charleston, S.C., when the Civil War began. A politically active Whig and friend of Henry Clay, Robertson was an early supporter of secession who would serve the Confederacy along with his five sons. Robertson had some military training—he attended the U.S. Military Academy at West Point from 1822 to 1826, though he did not graduate, and he led a militia company in the Second Seminole War.

Much of his adult life, however, was dedicated to studying medicine, first under a physician in Augusta, Ga., later at Charleston’s Medical College of South Carolina, and finally in his own thriving practice in Charleston, where he emerged as a leading researcher in the anesthetic uses of chloroform and ether and often lectured on obstetrics.

When the Civil War began, Robertson served as a surgeon of a militia company, and then in the larger Confederate Medical Department. He joined the Army Board of Medical Examiners in 1862, and was head of medical care at Fort Wagner later that year. By that fall, Robertson was assigned the responsibility of advising army doctors on major surgeries. In the final months of the war, Robertson evacuated Charleston with the Confederate forces that rushed northward to join General Joseph E. Johnston’s Army of Tennessee in North Carolina.

Robertson kept a diary of these final months of the war, during which he journeyed more than 900 miles, making his way to Richmond, Va., only to be sent home again. His writings capture the collapse of the Confederacy, the Christian faith that had sustained him throughout the war, his concerns for his family’s future, and his growing frustration with Confederate leaders and with waning civilian support.

[dropcap]I[/dropcap]n 2015, F.M. Robertson’s great-great-grandson, Thomas Heard Robertson Jr., published his relative’s 1865 diary. The following are excerpts from that publication, Resisting Sherman: A Confederate Surgeon’s Journal and the Civil War in the Carolinas, 1865.

Saturday, February 11

“The movements of Sherman in the direction of Columbia rendered the evacuation of Charleston a military necessity. If he intended to cut the communications with Charleston, by the different Rail Roads, we were shut up in Charleston, cut off from all supplies, and the loss of the army would be inevitable. Hence, in this event, the evacuation was necessary; and its prompt execution became a matter of great importance. If on the contrary, it was Sherman’s design to push on to Columbia, destroy every thing there and make a rapid march upon Genl Lee’s rear, and cut his communications by Rail Road, the evacuation was still more important, in order to combine and concentrate our forces to give him battle, and check his further progress. The evacuation having been determined on, our Board [of Medical Examiners] was ordered to Columbia. Events were hurried so rapidly upon one another, that I was compelled to go to Cheraw, and then await the movements of Genl Hardees army.

Sunday, February 19

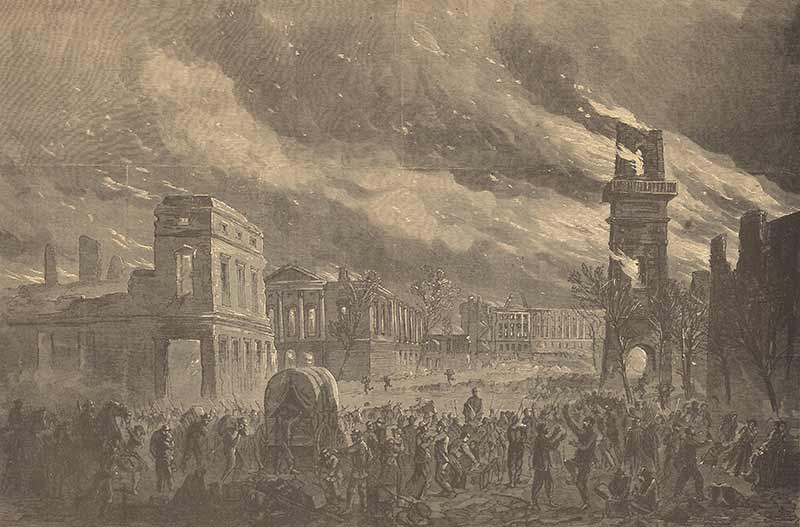

(two days after surrender and burning of Columbia)

I walked alone in the woods toward sundown….The laws of nature seemed to be in harmonious action….How great the contrast on turning to that moral world, in which man stands preeminent, among God’s creatures for good or for evil. What sin—what wickedness—what discord—what a conflict of the baser passions—what strife—what bloodshed—Oh that the wickedness of the wicked would come to an end!

It was during this solitary walk that I felt the full force of the sudden and rude shock which had, in a moment, severed all my domestic ties and driven me as a wanderer and refugee from my home and all its comforts, and those earthly endearments, which approximate the domestic circle, on earth, to that Heavenly inheritence [sic] which the blessed Redeemer has promised to His followers. When I thought of my afflicted wife, broken in spirits and bodily health; of my dearest [daughter] Marion and darling Annie [a young woman who lived in their household] left in the power of a relentless enemy, with no means of ascertaining their condition—when I thought of my dear boys—one in the hands of the enemy, the others in different parts of our Army—of my young and tender [son] Duncan, with the physical frame of a mere child; of Joe [young man who lived in their household] almost left alone and helpless without a friend, of [sons] Righton and Henry, separated from their dear families—of [son] Jimmy, in command which would be made to bear the brunt of battle in case of an engagement—my soul was shaken with anguish, and I wept as for a departed first born.

Amid this solitude…I poured out my soul in earnest prayer to that God Redeemer who is ever gracious to the repentant and contrite sinner. He, and He, alone, knows when, if ever, upon earth these broken ties are to be reunited. Let us abide His time and bow to His dispensations and chastenings [sic].

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]My soul was shaken with anguish, and I wept as for a departed first born[/quote]

Friday, February 24

Some soldiers belonging to the 5th, 32nd, and 47th Georgia Infantry came to the house yesterday evening asking for something to eat, and offering to purchase potatoes &c. The family kindly furnished them with food. If these men are without food, then there is a great fault somewhere and it should be speedily corrected, as the whole country has been stripped of subsistence by the government, and commissary stores are now accumulated in large quantities at Florence and this place. This matter should be looked into and the people, who have barely reserved sufficient subsistence for the non combattants [sic] thrown upon them, should be relieved from the straggling bands, by proper enforcement of discipline and care, on the part of the officers….I fear, from what I can gather from the straggling soldiers, that our troops are greatly dispirited, and are beginning to fail in self reliance. Oh for a living and energizing faith to bring our people up to the high standard of our cause.

Friday, March 3

I was aroused at half past one o’clock A.M. by a message…that trains were in motion….I packed in a hurry, and was off in a moment, for the field—crossed the brigade [over the Great Pee Dee River] at daylight—made four miles over terrible roads and stopped to feed and breakfast at 10 o’clock A.M. We had scarcely unhitched our animals when heavy artillery firing, with musketry, was heard in the direction of Cheraw. Supposed to be an engagement between our rear guard and the advance of Sherman. We resumed our march at 12 o’clock and continued it until 2 o’clock P.M., when we encamped for the night, to allow the trains, and troops in the rear, to come up.

Sunday, March 5

Resumed my journey with the Army toward Bostwicks Mills, about fourteen miles from Rockingham, in the direction of Asheboro. Weather clear windy and cold. Heard artillery firing in our rear about 11 o’clock. What a terrible thing war is—and above all this war. Besides the destruction of human life, and the utter devastation of the Country, it seems to wipe out the existence of God and the Sabbath. I was surprised at the number who did not really know that it was the Sabbath. Swearing is a crying sin in the Army. How shocking, on this sacred day, to hear the terrible oaths that are poured forth on all sides.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]What a terrible thing war is….it seems to wipe out the existence of God and the Sabbath[/quote]

Wednesday, March 8

Left the renowned city of Carthage at 6 1/2 o’clock A.M. and bid adieu to the consuming of apple jack and feminine representation of the [snuff] dipper class. The road to Fayetteville had once been a plank road, but was now in a dilapitated [sic] condition; but with the labor of the pioneer corps under the engineers, which preceded us, it was better than the ordinary dirt road. It rained all day. Made nineteen miles and encamped at a place called Johnsonville. It consisted of one house and a store. It rained and blew at such a rate that we could, with difficulty, get dinner and supper, which are usually compressed into one. Our mess had purchased some chickens at $5 a piece, and eggs at $3 per dozen—and we finally had rather a better dinner than usual. The house was occupied by a Mrs. Morrison, whose husband was in Genl Lee’s army. She kindly gave Major [S.L.] Black and myself a bed to sleep in, and put Major [John H.] Scriven on the floor on a comfortable pallet, and would not receive a cent from either of us. This was very kind, but she not only dipped but actually had a quid of the genuine Virginia weed stored away in her cheek. I was on the point of asking her if she had a tumor in her cheek, when it suddenly shifted to the opposite side, and save me from an unpleasant dilemma.

Sunday, March 12

[approaching Raleigh]

Arrived at Mrs. Banks’ at 3 o’clock P.M. Like all persons on the road she was evidently expecting to be plundered by the Yankees and seems to have stripped her house of all the good furniture and bedding, leaving just sufficient to give the house and premises the appearance of belonging to a person in very moderate circumstances. She had secreted all her valuables and provisions, merely leaving sufficient to make a fair show, as she intended to remain herself. She had several sons and one son-in-law, who should have been in the regular army. They are fine-looking, hearty, robust and young. They belong to what is termed, in North Carolina, “the home guard,” and I have no doubt they will guard their homes until the Yankees come, and then take their heels and skulk in some hiding place instead of meeting the foe like true men.

The old lady asked my opinion about the ultimate success of our cause. I unreservedly expressed my firm belief in our ultimate triumph, and spoke in terms of censure of those who for a respite from the present hardships of the war were willing to surrender, and go back into the old union. She replied, evidently looking upon the dark side, that she hoped we would succeed, but she always thought it was wrong to remove the old flag. God said we “must not remove the ancient landmarks.” This remark and an attempt to justify it by a bungling quotation from scripture, shows the superficial view that many take of this great struggle.

Monday, March 13

Arrived at Raleigh at 2 o’clock P. M. and stopped at the Yarborough House. Had a tolerable dinner but it is a dirty and filthy Hotel. I reported to Genl Johnson immediately. He gave me an order to report to the Surgeon General in Richmond; I shall probably leave tomorrow at 1 o’clock P.M.

[quote style=”boxed” float=”right”]I am thankful to the good providence that has spared Jimmy’s life in a contest in which so many have fallen to rise no more[/quote]

Thursday, March 16

At daylight had only progressed eleven miles from Danville. Still raining and blowing. It commenced clearing off before midday, and it was a great relief to the respiratory organs to raise the [train] windows and inhale the pure air. When we approached the junction of the Southern Rail Road from Petersburg, with the Richmond & Danville Road, we saw the evidences of strife in the burnt houses, tanks and bent iron….Arrived at Richmond at 1 o’clock P.M.

Friday, March 17

Reported to the Surgeon General at 10 o’clock this morning. He was polite….I took a seat and had a long chat with him. Upon receiving my communication from Florence enclosing [Dr. James Edwards] Holbrooks resignation and stating that I could not get to Columbia, the board was dissolved and Dr. [Francis Turquand] Miles and myself ordered to report to [Dr. N.S.] Crowell for hospital duty. I told him it was probable I should not be able to find Dr. Crowell. He directed me to go to Chester, and if I could not find Crowell, to report back to him by letter. He voluntarily told me that, as I had been broken up in my family arrangements, I could take as much time as I desired to arrange my affairs. He gave me transportation to Chester. I wrote my dear wife a short open letter—all that was admissible, through Coln [Robert] Ould, the commissioner of exchange, to go by way of New York, by the flag of truce boat. God grant that it may get to her. Called upon the paymaster and Quarter Master, and drew my pay up to the 1st of March and commutation for quarters and fuel up to the day I left Charleston. This was a lucky hit.

Saturday, March 18

Settled my bill at the Spotswood, which was $105 for self and servant [slave, Henry Sutcliff], and left Richmond yesterday evening at half past six o’clock. Cars literally packed, inside and out, with returned prisoners, who have just arrived by the flag of truce boat. Fell in company with Mr. Baggot from our City who had been in prison sixteen months, also Lieut. [J.] Hopkins and Mr. Williams, both of Charleston, who had just been released. I was indebted to them for a seat. When the cars were opened, Williams & Hopkins rushed in, secured seats and then hoisted the window and drew Baggott and myself through it into the car. Without a resort to this expedient, I should have been left in Richmond another night.

Sunday, March 19

The Raleigh train arrived at one o’clock P.M. and, to my surprise, I found [son] Jimmy on board, with a number of others, wounded. There had been a severe engagement near Averysboro [sic] about twenty-eight miles from Fayetteville on Thursday the 16th inst. lasting about six hours…

Jimmy was wounded by a minie ball…passing obliquely through the calf of the left leg. The wound is painful but, I trust, not dangerous. I am too thankful to the good Providence that has spared his life in a contest in which so many have fallen to rise no more. It was providential that I was detained here, as it will enable me to take him on with me to Chester, and take charge of his case myself. Liets. [Eldred S.] Fickling and [Thomas Price] Mikell, Mr. Jenkins Mikell’s son, determined to go on with us. Fickling was wounded in the leg below the knee, and Mikell in the foot, by a fragment of shell.

Sunday, March 26

Jimmy had a bad night, until I gave him half a grain of sulphate [sic] of morphine. He then rested well, but had considerable fever during the night. The wound is suppurating freely at both orifices, but there is an erysipelatous blush for some distance around the orifice exit which I do not like.

Tuesday, March 28

Jimmy continues to improve, and is about the house on

his crutches.

Thursday, April 6

The report of the evacuation of Richmond was confirmed today. The mere occupation of Richmond by the enemy is nothing, but its suddenness and the defeat of a portion of our army, with the inevitable loss of life, and wounded and capture of prisoners, makes it a disaster. This again shows the want of decision of character and delay in our authorities.

Saturday, April 8

A large number of refugees from Richmond and Petersburg arrived in the Charlotte train today, Government officers, Senators and members of Congress—Many of them with families and an immense amount of baggage. What a leveller [sic] war is. All had to take the same mode of conveyance—a common quartermasters waggon [sic]….Senator [Louis T.] Wigfall’s family crammed into one, with as little ceremony as a camp woman and her brats….

Sunday, April 9

[H]ow full of grief and trepidation are our hours of prayers and meditation. An exile from my home, with no intelligence from those loved one who are in the enemies lines, my mind is constantly agitated and troubled with doubts and fears. Their hearts, too, must be a prey to untold anxieties and fears in relation to the safety of the boys and myself.

[dropcap]O[/dropcap]n Sunday, April 16, 1865, one week after Confederate General Robert E. Lee surrendered the Army of Northern Virginia, Dr. F.M. Robertson reached Augusta, Ga. He closed his journal a week after that, commenting “I shall make no comment, at present, upon the Sad condition of our cause, but leave it in the hands of God who works in His own mysterious ways. Oh that He may preserve my darling wife and dear children, and bring us together again.”

Robertson and his family would reunite later that year in Charleston; somehow he and all five sons survived the war, with only two of them receiving wounds. Robertson returned to his prewar career and served as a professor of obstetrics at the Medical College of South Carolina in the late 1860s, and later as Dean of the College, until his retirement in 1873. A former Whig, he became active in Democratic Party politics, especially at the local and state level. He died in 1892, at the age of 86.

His diary offers superb insights into elite white Southerners’ determined loyalty to the Confederate war effort, frustrations with military and civilian leaders, the faith that sustained Southern families, and the chaotic collapse of the Confederacy.

Susannah J. Ural is co-director of the Dale Center for the Study of War & Society at the University of Southern Mississippi. Resisting Sherman: A Confederate Surgeon’s Journal and the Civil War in the Carolinas, 1865, is edited by Thomas Heard Robertson Jr., and available from Savas Beatie books.