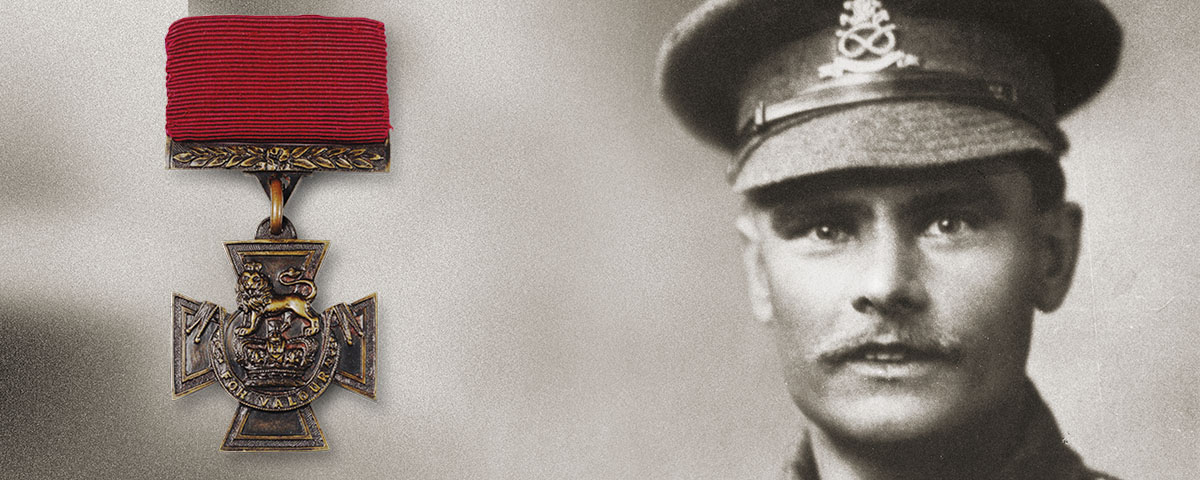

British army Lance Corporal William Harold Coltman received his nation’s highest award for combat valor while serving on the Western Front in 1918. Like U.S. Army Corporal Desmond Doss in the next world war, Coltman was a pacifist who refused to bear arms and instead served as a combat medic. Yet neither backed down under fire. Doss received the Medal of Honor; Coltman the Victoria Cross.

In 1915 Coltman, a deeply religious member of the evangelical Christian Plymouth Brethren, enlisted in the North Staffordshire Regiment and was assigned as a stretcher-bearer. Though a slight man of just 5 feet 4 inches, he routinely carried larger wounded men to safety. In February 1917 near Monchy-le-Preux, France, the medic received his first of two Military Medals (equivalent to the U.S. Silver Star), after an officer leading a wire-repair party was shot through the thigh and disabled in no-man’s-land. Coltman unhesitatingly moved forward and dragged the officer to safety, all the while under fire within sight of the enemy lines.

Coltman earned his second award of the Military Medal for actions near Lens over a period of several days in June 1917. When an incoming mortar round set fire to a ammunition dump, he risked death to help secure ordnance. The next day a mortar shell ignited the company HQ, and Coltman rushed in to treat the wounded. Days later, when a dozen men were buried alive in a tunnel collapse, he organized a rescue party to dig them out and rendered aid to the survivors.

Weeks later Coltman was awarded the Distinguished Conduct Medal (equivalent to the U.S. Distinguished Service Cross) for treating the wounded while under heavy fire over a five-day period. He even crawled into no-man’s-land at night to search for those needing rescue.

In late September the medic earned the bar to the Distinguished Conduct Medal at Bellinglise, as Allied forces broke the vaunted Hindenburg Line during some of the fiercest fighting of the war. Going for days without sleep, Coltman repeatedly braved heavy German machine-gun and artillery fire to retrieve wounded men from the forwardmost British positions. Many of those he rescued had important intelligence to report.

On Oct. 3–4, 1918, scarcely a month before war’s end, the British suffered a setback at Mannequin Hill, northeast of Sequehart. As they withdrew, they were forced to abandon their wounded on the battlefield. According to his Victoria Cross citation, Coltman “went forward alone in the face of fierce enfilade fire, found the wounded, dressed them and on three successive occasions carried comrades on his back to safety, thus saving their lives. This very gallant NCO tended the wounded unceasingly for 48 hours.”

King George V awarded Coltman his Victoria Cross at Buckingham Palace in May 1919. (By then the French government had also awarded the British medic the Croix de guerre.) After the ceremony Coltman returned home to Burton Upon Trent—modestly avoiding a reception there in his honor—and went to work as a groundskeeper in the town parks. During World War II he was recalled to active duty, commissioned as a captain and commanded the local Army Cadet Force. Coltman retired from his job with the parks department in 1963 and died in Burton Upon Trent in 1974 at age 82. He had remained a lifelong member of the Plymouth Brethren, which never recognized his military decorations, as they had stemmed from human conflict and been granted by the hand of man and not by God. The selfless Christian pacifist medic likely didn’t mind.