In November 1914, American voters in seven states were to consider a proposed Constitutional amendment that would enfranchise women. That September, the suffragist movement prepared to employ a new medium: a cinematic thriller made to appeal to the men who would be casting ballots by highlighting scenes of physical violence, kidnapping, fire, and child labor. To make the movie, producer William N. Selig had worked closely with the National American Woman Suffrage Association and activist Ruth Hanna McCormick. Selig shipped a pre-release copy to Chicago city censor Major M. L. C. Funkhouser and the National Board of Review of Motion Pictures in New York City. Both censors reflexively cut an entire reel that portrayed a male assailant and a woman fighting hand to hand until, using scissors, she stabbed him to death. A bowdlerized Your Girl and Mine circulated nationwide for the next two years, coming to an untimely demise but not without leaving a memorable imprint.

The July 1848 Woman’s Rights Convention at Seneca Falls, New York, inaugurated a prolonged campaign on behalf of voting rights for American women. Decade by decade the movement grew, developing into multiple organizations advocating enfranchisement through protests, marches, and lectures. At every step opponents like U.S. Senator Ben Tillman, Sr. (D-South Carolina) offered resistance, but suffragists persisted, adopting new media—postcards, posters, sheet music lyrics, pageants, and newsreels—to enlist, educate, and invigorate supporters. In 1914, an unlikely alliance formed between the movement and the motion picture industry. The result was a proto-feminist action film meant to challenge gender stereotypes and bring the suffragist message to millions of moviegoers. That ground-breaking film was titled Your Girl and Mine.

The male-dominated motion picture production companies of the early 1900s mostly frowned on woman suffrage. The movement came in for relentless cinematic parody and ridicule; many moving pictures made a point of depicting women as combative shrews or hapless spinsters. Shorts like A Suffragette in Spite of Himself (1912), Oh, You Suffragette (1911), Was He a Suffragette? (1912), A Cure for Suffrage (1913), and A Busy Day (1914) featured male actors in drag flamboyantly playing what Kay Sloan in her book The Loud Silents called “man-hating suffragists, bumbling husbands and confused or neglected children.” Intended to make females the butt of jokes, these vehicles instead rallied women and attracted men to a previously obscure cause.

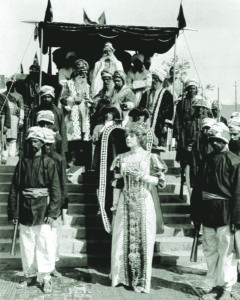

Gaining knowledge and expertise, many filmmakers were producing probing pictures revealing the medium’s power to shape public opinion. In his 1909 one-reeler A Corner in Wheat, David Wark Griffith—soon to be better known as “D.W.” and as the creator of the far more controversial The Birth of a Nation—wove film, politics, and social issues into a compelling demand for change that inspired middle class moviegoers to seek social and economic reform. Griffith’s work resonated strongly with other filmmakers who in such films as The Power of the Press (1909) and The Jungle (1913) confronted inequalities and injustices. Cinema emerged as a powerful tool with which to energize Americans on behalf of governmental change. The Adventures of Kathlyn, a 1913 13-part serial by Chicago-based Selig Polyscope Pictures, made history by introducing what became known as the “cliffhanger” episode ending and by featuring as its protagonist a strong, independent woman.

Suffrage organizations quickly grasped moving pictures’ power to persuade. In 1912 this awareness led suffragists to convince production companies to make one- and two-reel films on the movement for theatrical distribution. These shorts introduced movement leaders, explained the cause, and promoted its advancement. The Woman’s Political Union partnered with The Eclair Film Company of Fort Lee, New Jersey, to create the 1912 comedy Suffrage and the Man and in 1913 to bring out What Eighty Million Women Want.

Also in 1912, the venerable National American Woman Suffrage Association, which dated to 1869, produced the short Votes for Women in conjunction with Reliance Films, also based in Fort Lee. NAWSA was known for chronic caution and a tendency to delay and even squelch actions rather than risk embarrassing the cause. Movie magazine Photoplay called the group’s unexpected step into cinema “one of the best publicity moves which the Suffrage Association has yet taken.” Votes for Women turned out to be a great fundraising tool, a draw for local and state meetings featuring Dr. Anna Howard Shaw, Jane Addams, and other movement figures, and a calling card for the group’s reform-minded idealism.

In 1914, Nebraska, Missouri, Nevada, Montana, Ohio, North Dakota, and South Dakota were to hold elections regarding women’s voting rights, with the U.S. Congress set to vote in February 1915 on a proposed Constitutional amendment establishing woman suffrage. In its attempt, as the Chicago Examiner put it, to “accomplish as much for their cause as the novel, Uncle Tom’s Cabin, did for the anti-slavery movement,” NAWSA adopted cinema as a fund-raising and propaganda tool. The organization predicted that its productions would overshadow any previous release addressing suffrage. The aim, Shelley Stamp writes in Movie-Struck Girls, was to straddle the line between conventional views of women and motherhood and advocating bigger societal roles and civil rights for women.

The New York Times and other papers reported on July 2, 1914, that the New York Woman Suffrage Association was offering $50 for a “graphic” story that would “put suffrage before the people in a popular way.” The winning idea would be adapted as a photoplay—the term then used for “script”—by a major production company and produced as an eight-reel feature starring well-known performers and suffrage movement leaders. The competition was open to all, but the organization took care to invite well-known writers and suffrage advocates Irvin Cobb, Rupert Hughes, and Charlotte Perkins Gilman to compete.

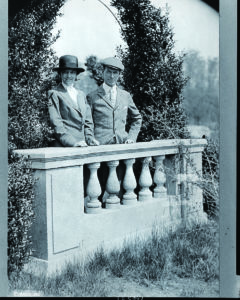

Ruth Hanna McCormick was tired of NAWSA’s wary plodding. A strong-willed heiress to political power and a newspaper tycoon’s wife accustomed to flexing economic muscle, she was a daughter of Illinois Republican kingpin and former U.S. Senator Mark Hanna and wife of Chicago Tribune publisher Joseph Medill McCormick. As a girl she had accompanied her father on campaigns; later, she served as his secretary. When her husband, a depressive with alcoholic tendencies, entered progressive politics, she helped with his equilibrium and his races. She herself joined the Progressive Party in 1912 to press for solutions to political, civic, and industrial problems. In 1913, Ruth McCormick shifted allegiance to NAWSA, bringing along her pragmatic outlook and her wealth. Within a year she was chairing the group’s Congressional Committee.

Convinced she could make a better film than NAWSA by playing to rather than preaching at moviegoers, McCormick contacted fellow Chicagoan William Selig. Selig’s company had made The Adventures of Kathlyn, the first motion picture serial with cliffhanger endings, and a massive hit. A self-designated “colonel” and former traveling magician, Selig had formed one of Chicago’s earliest film companies in 1896 and in 1909 established the first permanent moving picture studio in Los Angeles, California, behind a Chinese laundry. In 1910 Selig relocated that operation to a new production plant resembling the San Gabriel Mission on Glendale Boulevard in Edendale, and later setting up a huge zoo in East Los Angeles and in time shuttering his Chicago shop. McCormick pitched Selig Polyscope Film Company on an action-oriented suffrage film that she would bankroll. The reform-minded Selig bought in, reopening his Chicago studio so the film could premier in time to influence the November elections. He assigned Kathlyn screenwriter Gilson Willets to pen a thriller illustrating the proposition, as later stated by Moving Picture News, “that suffrage can be as thrilling as pirates or poisoned daggers.” Other themes would include factory worker rights, improved tenement conditions, the eight-hour workday, and abolition of child labor.

Bowing to McCormick’s ideological savvy and Selig’s business clout, NAWSA dropped its film plans and threw in with the pair. The expanded alliance’s aim “was to produce a photoplay which would appeal to every man and woman regardless of whether they knew anything about the suffrage movement or cared anything about it,” The Chicago Examiner wrote. “There are no long-winded arguments in Your Girl and Mine…it is packed with thrills and ‘action,’ which serve even better, we think, to carry our message,” McCormick declared. “We are going to reach people who flatly refuse to read our neat, cogent little pamphlets. If our plans go through, there will not be a spot in this country, from the mining camps of Alaska to the everglades of Florida which will not understand, vividly, what women mean when they talk about ‘the right to vote.’”

With McCormick as an adviser, the Selig company dotted the film’s 400-plus member cast with stage stars. Veteran performer Katherine Kaelred would play a lawyer, rising ingenue Olive Wyndham would star, and Grace Darmond would reappear throughout as “Equal Suffrage,” a symbolic figure who makes clear the moral encountered in every plot turn. NAWSA leader Dr. Anna Howard Shaw would portray herself addressing a suffrage convention. Giles Warren, supervising producer of the Selig Chicago lot, directed. Warren conferred daily with McCormick on production and adherence to message.

McCormick’s enthusiasm convinced suffrage supporter Selig to reopen his recently mothballed lot at Western Avenue and Irving Park Road. Producing the film in Chicago rather than Los Angeles allowed McCormick greater control over its production, as well as access to realistic shooting locations.

Synopsizing the seven-reel Your Girl and Mine, a copyright notice provided to the U.S. Library of Congress says the action occurs in an “unnamed non-woman suffrage State” whose laws oppress women. Heroine and heiress Rosalind Fairlie marries male lead Ben Austin. The wastrel Ben emotionally abuses Rosalind and their children, draining his wife’s wealth to pay his debts. When Ben comes to the room of Kate Price, his former mistress, Kate confronts him. He bullies her. They fight. Kate stabs Ben to death with a pair of scissors. Freed of her abusive spouse, Rosalind seeks custody of their children—but under patriarchal guardianship laws, Austin has willed the children to his father. The old man puts his oldest grandchild to work in a factory. Rosalind rescues the children from their terrible circumstances; the authorities arrest her and charge her with abducting her own offspring. The trial reveals how the law facilitates Rosalind’s persecution, suggesting that if women were able to vote, the result would be more humane outcomes for women, children, and the working class.

An Examiner report claimed every incident dramatized in Your Girl and Mine arose from the life of Ben Tillman Jr., son of the South Carolina Senator known as a sworn foe of woman suffrage. When his wife divorced him and won custody of their two children, the younger Tillman fought her in court. His father tried without success to get custody of his grandchildren. In announcing the film’s New York City release, The Times stated, “The situations depicted are all based upon laws which are now operative in many States, and which suffragists believe are the best arguments for the need of giving woman a voice in the making of the laws under which she and her children live.”

Finding the picture’s pivotal scene, a fierce portrayal of female rage, too graphic, the city of Chicago and the National Board of Censors ordered that entire reel cut. Even so, many newspaper advertisements for the film incorporated a still of the violent scene.

Completed in late September, Your Girl and Mine premiered in a matinee at Chicago’s Auditorium Theatre on Wednesday, October 14. The audience reacted with enthusiasm. That day’s Daily Tribune noted that NAWSA intended to show the film in at least seven states, a women’s movement first. Mrs. Grace Wilbur Trout of the Illinois Equal Suffrage Association praised the film and its guiding spirit. “Mrs. McCormick should have the gratitude of every suffragist for the great idea of presenting the objectionable laws so concretely,” Trout said. Because Missouri was among states with women’s suffrage on the November ballot, Your Girl and Mine would screen there quickly, with all proceeds benefiting the National American Woman Suffrage Association.

To handle distribution and booking, Selig and McCormick engaged New York-based World Film Corporation, led by Lewis J. Selznick. “In less than half an hour after I met Mrs. McCormick I was a convert to her cause,” Selznick, known as “the P. T. Barnum of the motion pictures,” told the Minnesota Star Tribune. “I gave her $50,000 for her picture film and 25 per cent of the receipts and telephoned the results to my New York office and was told I must be crazy.”

A different story appears in a letter circulated by McCormick’s Congressional Committee. According to that document, the organization received 50 percent of gross earnings, thanks to Selznick’s interest in “promoting our cause.” World Film created coupon books NAWSA would sell, featuring “two 5-cent tickets and four 10-cent tickets,” redeemable in any theatre playing the film. State and local NAWSA affiliates kept 25 percent of coupon sales. The parent organization received a larger percentage of profits from the coupon books than from box office receipts, and the book tickets offered reduced prices to suffragists buying them.

In the letter, McCormick’s committee encouraged NAWSA members to support Your Girl and Mine and suggested ways to do so: appointing a woman in each state to manage screenings and related paperwork; having a woman in each city visit newspaper editors pitching story ideas and selling advertising, with an ally calling on theatre managers asking when they planned to show Your Girl and Mine and distribute information about the film; and arranging for local notables to attend openings. Accompanying the letter was a model letter to the editor drafted by McCormick, detailing how screenwriter Willets developed the story and set it in 1902, when the legal conditions featured in the film actually existed across the United States.

To ballyhoo Your Girl and Mine, World Film Corporation organized a special advertising department. That unit printed elaborate illustrated programs distributed at screenings as well as magazine and newspaper ads featuring both illustrations and production stills like those of the stabbing scene. Streetcar panels in black, white, and yellow, the suffrage movement colors, mapped which states had no suffrage laws.

Reviewers mostly heaped praise on Your Girl and Mine. Critic Vachel Lindsay described the photoplay as a pioneering and “crusading” film. Trade journal Moving Picture World wrote “…Your Girl and Mine proved that moving pictures…will accomplish more for the cause than all that eloquent tongues have done since the movement was started.”

The January 24, 1915, Atlanta Constitution stated, “Suffrage is the dominant motive of the production, but it is unquestionably a drama of heart interest and a vivid bit of real life.” The New Oxford, Pennsylvania, Item wrote, “It will bring on the argument that women are fighting for the ballot because their economic and social interests and demands that they share in government, and not merely because they want to vote for the sake of voting.”

Anti-suffrage groups and papers like The Reply denounced Your Girl and Mine, posting excerpts of editorials purporting to document falsehoods in the film, and mocking Ruth McCormick for financing the project. The Bridgeport, Connecticut, Evening Farmer compared suffragism to socialism and Mormonism.

As a gesture of support for the organization as it lobbied Congress in advance of the February 1915 vote on the national suffrage amendment, Your Girl and Mine screened in Nashville, Tennessee, at the November 1914 NAWSA National Convention. Screenings and related events, such as an exhibition in the New Hampshire Legislature under the auspices of Clementine Churchill, wife of the British political figure, sought to sway male voters and legislators.

Unlike general-interest features booked by theatre circuits across the country, Your Girl and Mine received only intermittent screenings whenever suffragists convinced local theatre owners to screen the film. This factor hurt revenues, particularly when the men the film was created for mostly failed to turn out at the box office.

Your Girl and Mine exerted little impact in western elections or on the U.S. Senate. Nevada and Montana approved woman suffrage but five other states voted down woman suffrage in November 1914. However, in the two years following its premiere Your Girl and Mine played in 24 of the 48 states, including communities in the South and Midwest dead set against woman suffrage. Despite Selznick’s efforts, distribution was not consistent enough to generate profits. Box office receipts failed to cover expenses like shipping, advertising, and printing. Your Girl and Mine did inspire female viewers to continue the suffrage fight, however. The 19th Amendment passed Congress on June 4, 1919 and was added to the United States Constitution on August 26, 1920. The same year NAWSA reorganized as the League of Women Voters.

Wearied by producing, distributing, and promoting Your Girl and Mine, Ruth McCormick stepped away from NAWSA in 1915 to raise her children and nurse her alcoholic husband. She served on the Republican National Committee’s Executive Woman Committee 1920-24. Joseph McCormick died in February 1925. Seven months later his widow announced she would seek the Republican nomination to run for her late husband’s old at-large seat in the Illinois House of Representatives. Suffragist Ida Clyde Clarke declared Ruth McCormick to be one of three women equal to the task of being President, along with philanthropist Anne Morgan and tart-tongued writer and socialite Alice Roosevelt Longworth.

Astute and savvy, McCormick exhibited great skill and discipline. Visiting every town in Illinois, attending ward meetings, and appearing at African American churches, McCormick sailed away with the 1928 election, winning the at-large seat by nearly 500,000 votes. Within a month of taking her seat, she declared her candidacy for the 1930 U.S. Senate race, the first woman to campaign for that chamber. The race would be a grudge match pitting McCormick against incumbent Senator Charles S. Deneen (R-Illinois) who four years earlier had gained his seat by beating Joseph McCormick. Deploying her fortune, McCormick spent lavishly on ads, rallies, and campaign materials. She confronted Deneen head-on, in person and in print, defeating him by around 200,000 votes. The Tribune called her nomination “the first conspicuous and unequivocal acknowledgement of the full implication of the Nineteenth Amendment.”

However, going into that fall’s general election, McCormick unexpectedly shifted positions on key issues. For example, she threw her full support behind Prohibition as Illinois was turning wet. She spent heavily and visited every county but lost to Democrat J. Hamilton Lewis. She retired from political life. Ruth Hanna McCormick died on New Year’s Eve 1944 at her home in Chicago.

Once Your Girl and Mine completed its two years in distribution in 1916, the handful of release prints, relegated to storage in vaults, never were screened again. Like 75 percent of all silent motion pictures produced in the United States, Your Girl and Mine disappeared, a victim of nitrate-based film’s tendency to decompose, storage costs, production company closings, and the addition of sound to cinema, which for a time made silent films seem so old-fashioned that they simply were junked. One of many powerful tools inspiring women towards political freedom, Your Girl and Mine in its fleeting existence served a great purpose, illustrating in compelling cinematic terms the profound need for woman’s suffrage and giving dramatic voice to women’s demands and issues.