IT WAS ABOUT 3 A.M. on D-Day when I left the troop transport USS Samuel Chase for a landing craft headed for Omaha Beach. I was 23 at the time: a first lieutenant with the 1st Engineer Combat Battalion. On D-Day, I was serving as a liaison officer on the staff of Major Edmund F. Driscoll, the commander of the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment, 1st Infantry Division. My mission was to stick close to Major Driscoll so that he could communicate with engineers if he needed them. My company “headquarters” consisted of me, a radioman, and a runner.

Two battalions of the 16th Infantry Regiment—the 2nd and the 3rd—were preceding us in the first wave of landings. The 1st Battalion was to land behind the two assault battalions roughly an hour after the first wave—about 7:30 a.m. Our assumption was that the beach would be secure by then and our work would start a few hundred yards inland, where the engineers would support the infantry and armor by filling antitank ditches, removing mines, and demolishing concentrations of barbed wire.

The landing craft loaded a few at a time, with the full ones circling until all were loaded so we could arrive at the beach at the same time. I was in a boat with the 1st Battalion Headquarters. Major Driscoll was standing with his operations officer at the front, right behind the landing ramp. I was at the very rear, with my radio operator Doyle and runner Fitzwater. (I knew them only by their last names.)

I found myself standing in front of the famous Life magazine photographer Robert Capa. I’d seen him earlier aboard the Samuel Chase while we awaited departure in the Weymouth, England, harbor. The Chase had a gymnasium down below, where a huge relief map of the entire invasion area had been set up. I had gone to take a look at it with some other 1st Battalion officers when I noticed Capa there, trying to take a picture of the officers examining the terrain, and I worked myself into the group.

After what felt like an eternity, the landing craft from the Chase stopped going around in circles and headed for the beach. It was probably 15 miles away. Dawn broke and we could see other landing craft and a few naval vessels. Our column of boats deployed into a wave of parallel boats. It was very overcast. Nobody talked much and nobody cracked jokes.

As H-hour—the time when the landings were to begin—approached, we looked up, expecting to see the armada of bombers that were going to devastate the beach, but saw nothing but low gray clouds. At this point I was, of course, a bit apprehensive, but not terribly so. I was confident that the air force and the navy would by now have pulverized the beach defensives so completely that our main difficulties would be a secondary line of defenses and the inevitable counterattacks. The bombings alone would have left the beach area a maze of craters, with all the barbed wire gone and all the mines detonated.

When we were two or three miles from shore, Capa and I looked toward the beach and saw, here and there, puffs of black smoke and towers of water. “That must be the beach engineers blowing up the obstacles,” Capa said to me. He was referring to the plan for the specially trained battalion of engineers, who were supposed to land a minute after the first wave to demolish the obstacles. I thought the explosions looked like German shell fire but didn’t contradict him. He didn’t want to talk and I didn’t want to talk, and that was that.

From then on, we mostly stayed hunkered down and didn’t see much. All seemed to be smoke and mist ahead anyway. Suddenly I heard machine-gun fire, very loud. Bullets were bouncing off our boat. I looked up and barely made out the outline of a hill or bluff. What the hell? We were supposed to land opposite the E1 exit, a small road leading away from the beach—not the bluffs. From right behind me, the coxswain of the boat yelled, “Where do you want to land, Major?” Our boat was evidently free to land wherever Driscoll, the battalion commander, wanted. Driscoll waved frantically to the right—he seemed to feel that we were to the left of where we belonged.

The boat swerved to the right and, in so doing, tipped so far to the left that the whole scene opened up for an instant before our eyes. There were the antitank and antiboat obstacles (steel hedgehogs—like giant versions of jacks from the children’s game; wooden structures meant to overturn a boat; and wooden poles set at an angle with mines on their tips), all intact and now with a foot or so of water swirling around them. There were several tanks in the water, but what really caught my eye in that brief instant were men (and the bodies of men) lying on the shingle bank—the rocky strip of beach—just beyond the water’s edge. In a flash I knew this was the front line. The initial assault had failed! We had been stopped at the water’s edge just as German Field Marshal Erwin Rommel had promised.

The boat righted itself and more machine gun bullets bounced off the hull. The coxswain maneuvered a few yards to the right and then did a good job of working the boat between some of the obstacles. In the meantime we saw men apparently drowning in the water next to us. My radio operator, Doyle, panicked and created quite a scene. He was carrying a heavy radio on his back and was afraid of drowning if he fell in deep water. He said: “Get this off my back!” He told Fitzwater to take it off. I think he was yelling, but I’m not sure. I knew what was going on, yet I wasn’t thinking at all. Just get out of the boat fast; just get the hell out of there. Someone unfastened the radio and Doyle and Fitzwater decided to carry it between them using the carry straps.

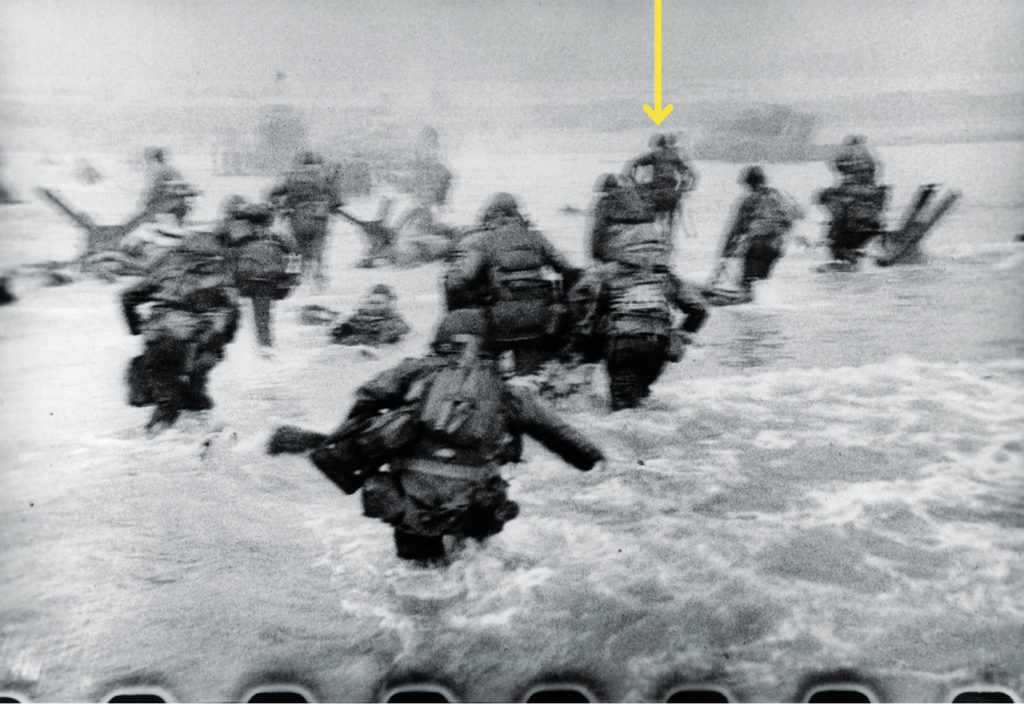

The boat’s ramp dropped down. Capa and I were in the right rear of the boat and were to leave at the right corner of the ramp. This I did, assuming my two men and Capa were right behind me. We rushed out into about two or three feet of water and headed for the beach.

I immediately thought of the film All Quiet on the Western Front and its images of the French and Germans getting out of their trenches to go “over the top” and into enemy fire. I’d first seen the film when it was released in 1930. I was 10 then, and it made a big impression on me. I told my friends about it; we all had cap guns and one guy had a “machine gun” cap gun. And we practiced how to fall dead in my backyard. I had become convinced I was never going to get myself in that situation.

I ran through the water toward a couple of the hedgehogs. I saw men and bodies gathered behind them and, for a brief instant, thought to join them. The thought passed, and I ran to the right and then headed toward a tank about 50 yards ahead. I don’t recall the noise, but at that moment I saw the splashes of machine gun bullets hitting the water immediately in front of me. The fire was coming from the right front and appeared to be a single machine gun firing. It was hard going through the deep water, but I ran on and pulled up on the left side of the first of three tanks that were just on the seaward side of the shingle bank.

The tide was coming in rapidly. I looked around and found Doyle and Fitzwater right behind me. We stopped on the left side of the left-hand tank and took cover from the machine-gun fire. I looked to my left and there was Robert Capa at the rear of another tank about 20 or 30 yards away, exposing himself to machine-gun fire, his camera to his eyes, shooting in all directions. He pointed his camera straight at me.

At about that time I became aware of little splashes and puffs of black smoke near me every now and then. The Germans were lobbing rifle grenades onto us—probably trying to hit the tank that I was crouching behind. The three of us moved up to the next tank, and then I saw Major Driscoll on the shingle bank. Still confused about where we had landed, I said, “Where are we, Major?” I guess it made me feel good to at least say something—or to discover that I was capable of saying something. He replied, “I don’t know, but I know we’ve got to get the hell off this beach.”

We stepped back to the water’s edge and then ran along the shore to the right for about 100 yards. There I saw the beach and all its horror: dead men, wounded men, some mangled by artillery shells, others running out into the water in little teams to rescue men or pull in wheeled carts of ammunition. I heard no sounds of crying men—in fact I recall no sounds at all: everybody seemed stunned and traumatized and strangely quiet. And then Driscoll veered to his left and up over the shingle toward the bluffs.

My mind returned to All Quiet on the Western Front. I thought, “It’s 1917 and I’m going ‘over the top.’” And I followed. ✯

—William M. Kays, the author of this first-person piece, earned an engineering degree at Stanford before joining the 1st Infantry Division in 1942. He served in Tunisia and Sicily, and participated in the D-Day landings—where Robert Capa captured him in some of his famous photos—and the Battle of the Bulge. Kays returned to Stanford after the war, eventually becoming its dean of engineering. He died on September 9, 2018, at age 98.

WHY THIS STORY MATTERS, ACCORDING TO A HISTORIAN

In early 2018, I received an email from Roger Lake, a longtime friend of Bill Kays, who was writing on Kays’s behalf. Bill, then 97, was a distinguished veteran of the 1st Engineer Combat Battalion, 1st Infantry Division. He had recently read my book The Dead and Those About to Die: D-Day: The Big Red One at Omaha Beach and wanted me to know how truly it conveyed a sense of what the invasion was like for him and his comrades.

Kays was particularly interested in what I had said about the famous photographer Robert Capa. In my book, I had argued that Capa couldn’t have been in the first wave of landings, as has been commonly assumed for decades. Given his ship of origination and the camera angle of his photos, he had mostly likely hit the beach in the second wave, possibly with the 1st Battalion, 16th Infantry Regiment. Bill could confirm that argument.

Aboard a second-wave landing craft bound for the beach, Bill had stood next to Capa and had repeated interactions with him. Furthermore, the photographic evidence supports what he says: Bill had identified himself and two soldiers of his liaison team in Capa’s photographs and could bolster that with precise recollections. With Roger’s assistance, I encouraged Bill to write and document everything he could recall of that traumatic D-Day morning.

In doing so, Bill has added something new to our understanding of Omaha Beach on D-Day morning. He has helped sharpen our contextual understanding of Capa’s famous photographs—truly the iconic images of history’s most significant invasion. My only regret is that Bill did not live to see his fine article published in World War II.

—John C. McManus, a Curators’ Distinguished Professor of U.S. military history at Missouri University of Science and Technology, is the author of 13 nonfiction books—three of them about D-Day and Normandy.