Larry D. Edgar is perhaps best known for depicting in oil and bronze well-known figures from Wyoming history—e.g., Tom Horn, Jim Bridger, the Hole-in-the-Wall Gang—but in Crossing the Divide the 73-year-old artist pays tribute to two overlooked hometown heroes. The oil-on-canvas shows brothers Ralph and Curtis Larsen riding their ranch in Meeteetse. You may not recognize their names, but Edgar believes you should.

“Their dad homesteaded that ranch in 1909,” Edgar says, “and they kept working, building that herd, and kept that ranch going for a long time.” Ralph died in 2008 at 89, Curtis in 2015 at 99. “Those kind of old guys are gone,” Edgar adds. “After we lost Curtis, I just thought I’d like to do a tribute to them, because they’re going away on us. That generation’s gone, and that was a tough, resilient generation.”

Edgar knew Crossing the Divide wouldn’t likely be a critical or commercial success, but it fit his ethos of remaining true to history. After all, the Larsen Ranch—now in the hands of the third and fourth generations—is among the largest deeded ranches in the state, and Ralph and Curtis are inductees in the Wyoming Cowboy Hall of Fame.

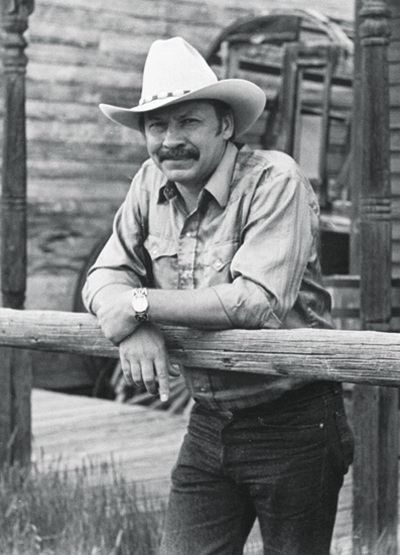

Edgar himself is a bit of a Wyoming legend. After tutoring under Indian artifact collector Adolf Spohr (1889–1966), the young artist majored in fine arts at Wyoming’s Northwest College. His late brother, Bob, founded the Old Trail Town museum in Cody in 1967, and that decade the brothers helped excavate Wyoming’s Mummy Cave, among the most comprehensive Paleo-Indian sites in the northern Plains. While archaeology interested Larry, art ultimately won out. He was invited to display at the 1986 Governor’s Invitational Western Art Show in Cheyenne, and his work has since garnered awards from the Wyoming State Historical Society and the Buckaroo Heritage Western Art Roundup in Winnemucca, Nev. He dabbled with bronze sculptures in the late 1980s and ’90s but prefers painting.

Edgar credits Nick Eggenhofer (1897–85), the prolific pulp magazine illustrator and Cowboy Artists of America member, for his success. “He made sure I didn’t try to paint my images ‘Hollywood West,’” Edgar says. “If you’re going to do something from the 1800s, make sure you do it the way it was—without the influence of Hollywood or the modern West. He really stressed that, and he’s right. If you want something that looks legitimate, you’ve got to do it the way it was.”

For Edgar the process starts with research, followed by visits to specific locations, during which he photographs and sketches the surroundings. “You’ve got to have [the scene] laid out in your head and maximize your composition,” he explains. “Then you use your photographs for backgrounds and details.”

His interest in the history of the region stems from childhood. “We were in the hills all the time, looking for arrowheads,” Edgar says of himself and brother Bob. “History was always a real passion, and our area had lots of it.”

What intrigues Edgar the most are Wyoming’s fur trade and outlaw history, his current work in progress focusing on the latter. Around 1892 each big area ranch hired range riders—“What they were,” Edgar bluntly concedes, “were killers”—to hunt down rustlers. But the artist’s rendering of three such range riders tracking a rustler took a back seat to the Larsen brothers. “This is really cattle country down here,” Edgar explains. “But it’s starting to fade. You can see the changes. Old ranches are being bought up by people who don’t have to make their living on them. Those kind of old guys are gone.” WW