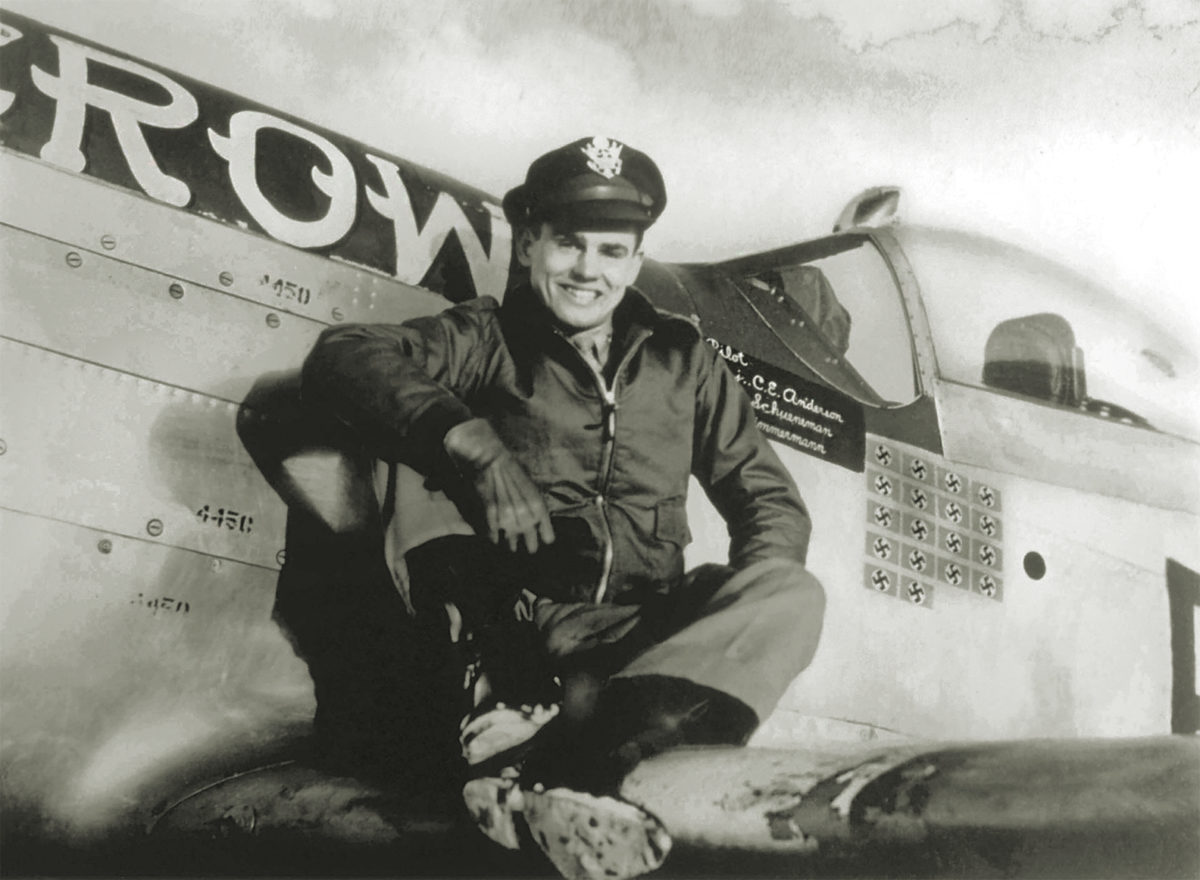

The 357th Fighter Group was the first in the U.S. Eighth Air Force to enter combat from the outset of World War II equipped with the North American P-51 Mustang. Credited with 595½ aerial victories—including a record 18½ Messerschmitt Me 262 jets—and 106½ aircraft destroyed on the ground, the group also produced a record 42 aces.

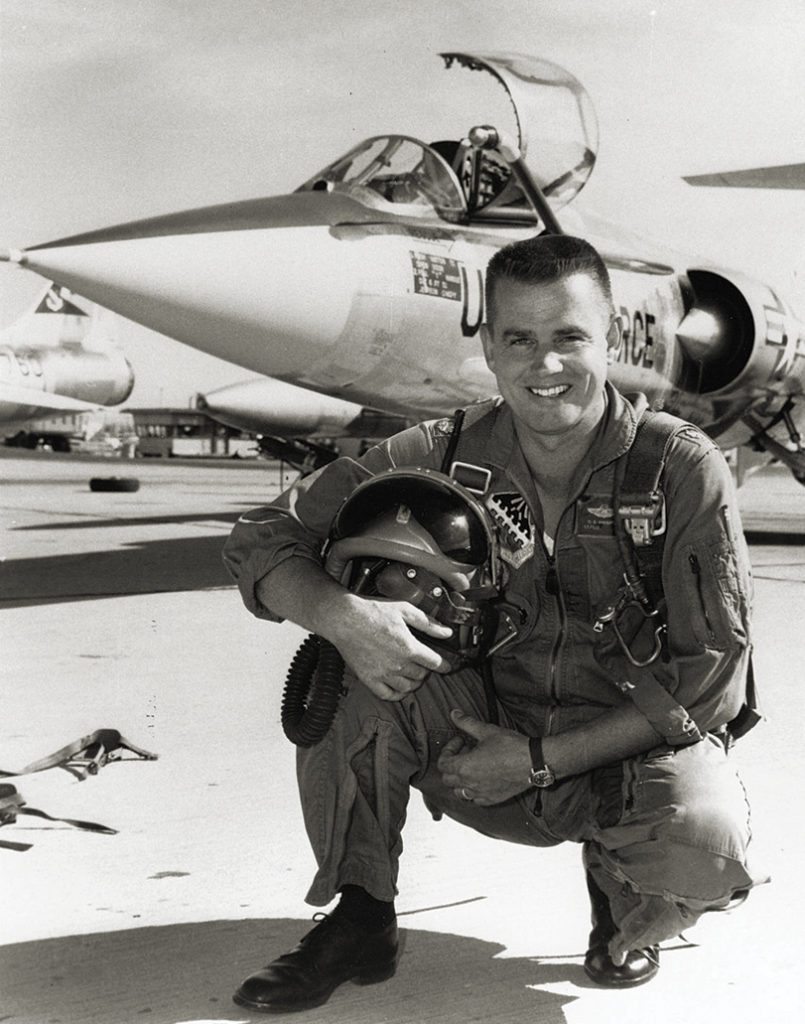

Of the 357th’s nine double and triple aces, one remains. With 16¼ victories to his credit, Clarence Emil “Bud” Anderson Jr., 100, is the highest-scoring living American fighter ace. His many activities in the postwar U.S. Air Force included flying Republic F-105D Thunderchief fighter bombers over Vietnam as commander of the 355th Tactical Fighter Wing from June to December 1970, before retiring on Feb. 29, 1972. On Dec. 2, 2022, the Air Force capped off his career by promoting him to the honorary rank of brigadier general.

As a boy growing up in Oakland, Calif., how early did you set your sights on aviation?

My brother and I both grew up fascinated by aviation. There was a mail plane flying by daily and at least one airport within 30 miles of us. Douglas B-18s were based at Moffett Field. Our parents would take my best friend, Jack Stacker, and me to the airport, dump us there and pick us up.

Did you have any flight background before enlisting in the U.S. Army Air Corps on Jan. 19, 1942?

I was already a private pilot—it helped in my early military training. I flew a 45 hp Piper Cub, a really early model. I flew tail wheel aircraft all the way up to graduation.

What was the situation when the 357th Fighter Group arrived at England’s RAF Leiston airfield on Jan. 31, 1944?

There was a “Pioneer Mustang Group,” the 354th of the Ninth Air Force, which lent its P-51s to the Eighth Air Force. We loaned some pilots to the 354th, and they were so wildly successful that the Eighth ordered P-51s and made us the first P-51 unit in the Eighth. They also fired all the generals in the Eighth and replaced Maj. Gen. Ira Eaker with Jimmy Doolittle. [Doolittle] took the calculated risk of changing the bomber escort procedure, with us not just escorting the bombers but eliminating the enemy fighters. It was pursue and destroy.

What do you recall of your first combat mission?

By February 5 the 357th’s complement of P-51s had reached 74, nearly its quota. Two nights later I flew down to the 354th at [RAF] Boxted with a half dozen others, assigned to make my debut the next morning. We weren’t too concerned until morning, when we learned the lark over France was to be, instead, an escort mission deep into Germany. The target was Frankfurt, 360 miles from our base in East Anglia. We were liable to see German airplanes up close on this kind of mission—Focke-Wulfs and Messerschmitts, good planes manned by experienced pilots. I had logged 893 flying hours already, but only 30 hours and 45 minutes of that in Mustangs, and what I was thinking about, before prodding the Merlin to life, was of not getting lost, not screwing up.

I was assigned to a veteran pilot, a fellow with a couple of kills already. We found the bombers in less than an hour. They would fly at 20,000 to 25,000 feet, and if the atmospheric conditions were right, they would leave enormous, billowing, cottony contrails that widened behind them for miles. We climbed to 30,000 feet or more and began flying zigzags above them, which was how the escorts (“little friends” to the bomb-er crews) stayed close to the bombers (“big friends” to us) and still kept up their airspeed.

Then someone calls, “Bogeys!” and I’m suddenly about as alert and fully alive as I’ve ever been in my life. The first thing I do is tuck in closer to my leader. And then up goes his wing, and he’s sliding away, and he’s yelling something. I do what he does, all the time looking around, looking down…and then here’s a Focke-Wulf Fw 190, a half mile off, maybe less. I’m almost upside down, and I’m looking straight up/down at this deadly and beautiful thing, robin’s egg blue with big black crosses, and the man I’m protecting is sliding in right behind it. “Mustang! Mustang! There’s one on your tail!” Huh? I look around. Nothing. The Mustang in front is lining up on the German now, and again through the earphones: “Mustang! Mustang! He’s still on your tail!” At maximum range he triggers his guns, sending a long, futile burst at the 190 with his four .50 calibers, and then he slides that Mustang up into the damnedest series of gyrations I ever did see. Somehow, I stay with him. It comes a third time: “Mustang! Mustang! He’s still on your tail!” And then a light winks on in my head. Maybe the Mustang he’s warning is me! I throw my airplane about, plummet down, look around…and see nothing. Now I’m feeling like an idiot. And worse, I suddenly notice—I’m alone over Germany. No. There’s a plane in the distance. I slide closer, warily. It’s clearly a Mustang, alone, like me. Against all laws of probability the plane is my leader’s.

Later, back at Boxted, sorting things out, we wondered if maybe someone might have mistaken me for a German closing on my own leader’s tail…but no one ever admitted to yelling the warning, which seemed a pretty good clue that somebody blew it and knew it and was embarrassed about it. Man, was my flight leader pissed! He could have gotten that Focke-Wulf, and he wanted the victory.

My first mission hadn’t been a confidence builder, exactly. But I’d seen the bad guys up close, and I was a little bit smarter by evening than I’d been in the morning.

How about your first confirmed victory?

Our first pilot to get a kill was not the sharpest knife in the drawer. On Feb. 20, 1944, 1st Lt. Calvert L. Williams of the 362nd Fighter Squadron got lost on his first mission. He came out of a cloud and suddenly found this German fighter alongside him, apparently just as lost. He just slid back and blew it out of the sky. So here I am, the hottest pilot in the whole world, and so far…nothing.

On March 8, 1944, we were heading home with 1st Lt. John B. England along with us. We saw a Boeing B-17 [Flying Fortress] below us, smoking, so we were headed over there when three Me 109s came up. We cut them off at the pass, and I saw one and said, “This one’s mine.” Our initial engagement was one of concentric circles, pulling a lot of g’s. I fired blind, and black smoke was coming out—I got him in the coolant system. He bailed out. I was patting myself on the back when there was a guy on my wing, and it was England, mask down and grinning. Then I thought, Wait, did Johnny England shoot that down from under me? After we had a debrief, I went straight to the officer’s club, and the first guy I saw was Johnny. He came running over, and I was thinking: What do I say? What if he claims it? Should I argue or what? Hell, I’m not sure myself! But I didn’t have to ask. “Goddamn, Andy,” he gushed. “Best shooting I’ve ever seen in my life! You hit that sonofabitch out there at over 40 degrees!” I said: “Aw, shucks, Johnny. Lucky shot. You know how it is.” And the moment he turned, I ran—literally—to get on the telephone and claim my first victory. [Editor’s note: England was also credited that day with his first of an eventual 17½ victories, placing him among the 357th’s leading aces. An Air Force base in central Louisiana is named for him.]

What were the circumstances of your double claim on April 11, 1944, in which you were credited with an Me 109G and a quarter share of a Heinkel He 111K?

On April 11 the target was a Focke-Wulf factory at Sorau [present-day Zary, Poland], deep inside Germany, and the Germans came up in force. While dropping my tanks and jamming the throttle forward, I picked out three Messerschmitts. They brought down two bombers beneath us, rolled over, went down and turned around, obviously trying to re-form up ahead for another head-on attack. I fell in with one. He breaks hard, I wheel about, see a large moving shadow on the ground, and I see my opponent reversing his turn, trying to come at me head-on. He doesn’t quite make it. The propeller flies off. The engine cowling is blown away. Then off comes the canopy, and out comes the pilot.

Now…what the hell was that shadow? The rest of my flight has caught up. “I think I saw a multi-engined plane heading west,” I tell them. We pick him out right away, a Heinkel 111 twin-engined bomber, scooting right along on the deck. He is trying to use his camouflage paint job to blend into the countryside. But in the bright sunlight his shadow betrays him. From slightly above and off to the side we attack, rolling over one at a time, making what we called a “high-side pass.” I go in first, set an engine to smoking. Eddie Simpson goes for the smoking left engine and blows it to hell. Bill Overstreet rakes the bomber from as close as 100 yards. Henry Kayser, a brand-new guy, hoses the cockpit until he runs out of ammo and burns his barrels out. I come around for a second pass and hit him from tail to cockpit until my ammo is gone too. Losing altitude quickly, the Heinkel pilot tries setting it down in a field, but there’s a pole in his path, and it tears the left wing away. The bomber slews around and explodes into flame. We pass over the wreckage and see two men jump out. One takes off, the other just stands there, looking up at us. I say, “Everyone get hits?” The answers come back, “Rog.…Rog.…Rog.” So we shared the credit, a quarter kill on each of our records.

Any special memories of the “double play” you scored near Strasbourg on May 27 or the “triple” southwest of Leipzig on June 29?

On May 27, 1944, the Luftwaffe came up in force, and I had my toughest fight ever, the “straight up” encounter I will always remember. We were high over a bomber stream in our P-51B Mustangs, escorting the heavies to the Ludwigs-hafen-Mannheim area. For the past several weeks the Eighth Air Force had been targeting oil, and Ludwigshafen was a center for synthetic fuels. We’d picked up the bombers at 27,000 feet, and almost immediately all hell began breaking loose up ahead of us. This was still over France, long before we’d expected the German fighters to come up in force. They’d worked over the bombers up ahead, and now it was our turn. I start to call out, “Four bogeys, 5 o’clock high!” We turn hard to the right, pulling up, spoiling their angle. The Me 109s change course, and we begin turning with them. The Mustang is a wonderful airplane, just a little faster than the smaller German fighters and also just a little more nimble. Suddenly the 109s, sensing things are not going well, roll out and run, turning east. Then one climbs away from the rest. I send Simpson up after him. My wingman, John Skara, and I chase the other three. I close to within 250 yards of the nearest Messerschmitt—dead astern, 6 o’clock, no maneuvering, no nothing—and squeeze the trigger. He slows, rolls over. I pour another burst into him, and the 109 falls into a spin, belching smoke. My sixth kill.

As we take up the chase again, two against two now, the trailing 109 dives for home, and the leader pulls up into a sharp climbing turn to the left, passing in front of us at an impossible angle. My wingman is vulnerable. I tell Skara, “Break off!” and he peels away. The German goes after him, and I go after the German. He sees me coming, dives away, then makes a climbing left turn. I go screaming by, pull up, and he’s reversing his turn—man, he can fly!—and he comes crawling right up behind me. He’s bringing his nose up for a shot, and I haul back on the stick and climb even harder. He stalls a second or two before I stall. Good old Mustang. He is falling away now, then he flattens out and starts climbing again, as if to come at me head-on. I decide to turn hard left inside him. I pull back on the throttle slightly, put down 10 degrees of flaps and haul back on the stick just as hard as I can. This time the Messerschmitt goes zooming straight up. I follow him up, and the gap narrows. He must know that I have him. I bring my nose up, he comes into my sights, and from less than 300 yards I trigger a long, merciless burst. The bullets chew at the wing root, the cockpit, the engine. There is smoke in the cockpit…and then he falls away, straight for the deck. No spin, not even a wobble, no parachute. At 25,000 feet I ease out of the dive and watch him go down. Eddie Simpson joins up with me. Both wingmen, too. Simpson, my old wingman and friend, had gotten the one who’d climbed out. We’d bagged three of the four.

As for the three [Focke-Wulf] Fw 190s I got on June 29, that just went bang, bang, bang. The last guy, he was on my tail once, and I had to shake him off, and throughout those maneuvers he was hard to get, but I finally got him.

Your last victory came on Dec. 5, 1944. What do you recall?

The quality of the Germans had gone down by then. One Fw 190 dived under the clouds; I just slid down and blew it up. I got two kills in that last fight.

So you emerged from your Air Force career without a scratch?

When it was done—the 480 hours of combat flying in P-51s and another 25 or so missions in Vietnam, almost all of those in F-105s—I never once suffered a hit in air-to-air combat. The sum total of the damage all my aircraft absorbed amounted to one small-arms round that found one of my wings during a strafing run after D-Day.

By then, we presume, you’d made up your mind about the P-51?

The P-51 was a great airplane. I think it saved the world.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.