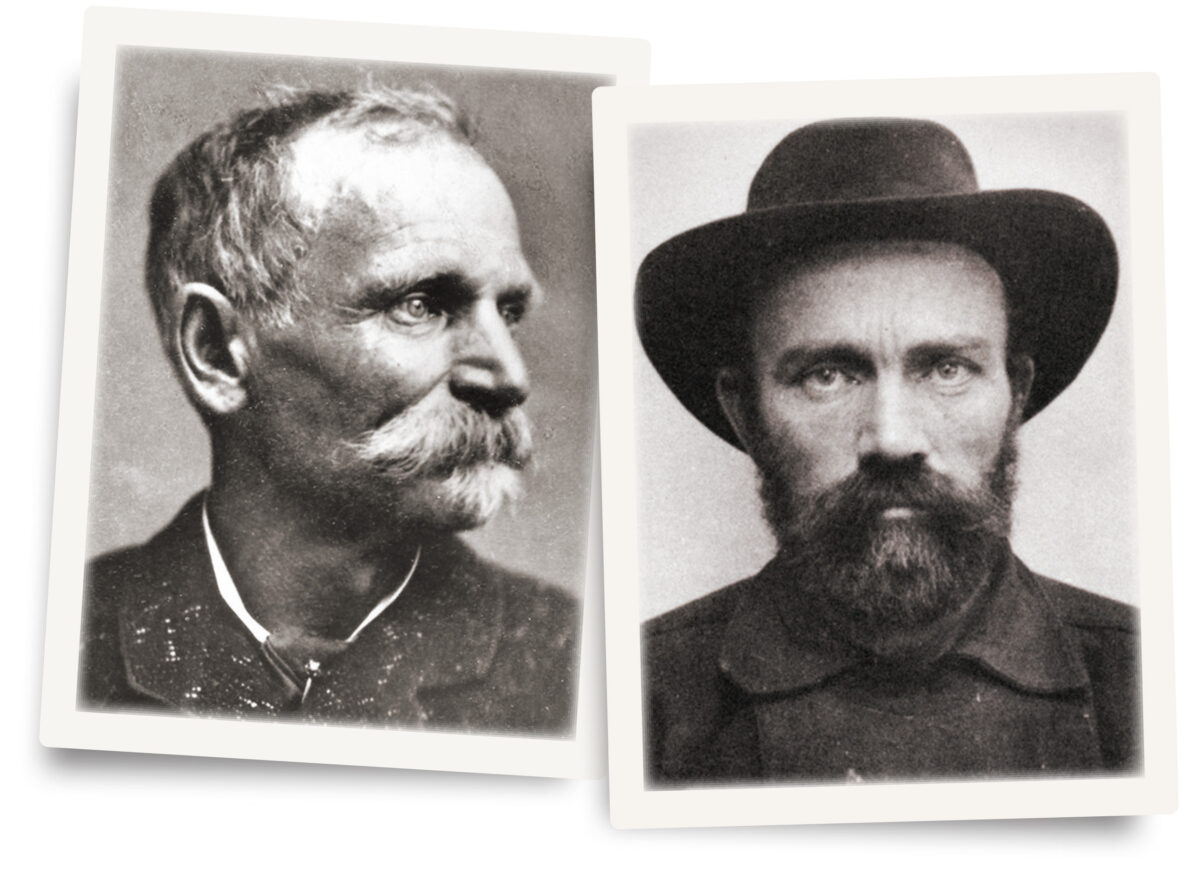

Ham White (aka Henry W. Burton, aka Henry Miller) committed at least two dozen stagecoach robberies or attempted robberies in Texas, Arkansas, Colorado, Arizona Territory and California in a criminal career that stretched from 1877 to ’91—with several interruptions for prison time. According to records from Wells Fargo & Co., the typical stagecoach robber, or road agent, reached the end of his career (one way or another) after one or two robberies. Thus, two dozen represents something of an achievement, albeit a dubious one.

An obvious basis for comparison is the legendary Black Bart. Widely considered history’s most successful stagecoach robber, he waylaid nearly 30 stages in the California gold country between 1875 and ’83, and possibly three more in 1888 after a sojourn at San Quentin State Prison. As he always robbed in disguise, the exact number is disputed. Black Bart seems to have served as a role model of sorts for White. Contemporary newspapers compared the road agents, and on at least one occasion, while confessing to a robbery, Ham claimed Bart as his inspiration.

Mark Dugan, author of the biography Knight of the Road: The Life of Highwayman Ham White, deems his subject “the premier stagecoach robber in the United States,” noting that the determined road agent resumed his career in the wake of several extended prison sentences. In his 1899 autobiography A Texas Ranger, Napoléon Augustus Jennings asserted White “has been confounded many times with the notorious Black Bart but was far more daring than that ‘knight of the road.’”

Just how well does White stack up to the reputed master road agent? Does he fall short, meet or exceed the benchmark set by Black Bart?

White’s Young Career

Hamilton White III was born in Bastrop County, Texas, on April 17, 1854, to a wealthy farm family with respectable acreage. In 1875, at age 21, he ran afoul of the law over the revenge killing of neighbor James Rowe, who in 1867 had gunned down Ham’s father in a dispute over a hog range. Wounded in the knee by return fire from Rowe’s brother, White limped noticeably for the rest of his life. With a price on his head, he fled to west Texas, where for a year or so he made his living as a buffalo hunter. Escaping from two sets of would-be captors, White embarked on his first series of stagecoach robberies in 1877.

That March 7 White stopped the Waco-to-Gatesville stage at pistol point, relieving the driver of the U.S. mail and robbing six male passengers (four by some accounts), though allowing each to keep a dollar or two, one to keep his watchand refusing to rob the lone female passenger. That month, after paying a visit to his family in Bastrop County—heedless of the outstanding arrest warrant—White stopped four more Texas stages, two in one day. Remaining in the saddle for most of these robberies, he again targeted the U.S. mail and affluent male passengers.

After the neophyte highwayman indulged in an ill-advised spending spree, Texas Rangers in Luling arrested White on March 28 and turned him over to federal authorities in Austin. Convicted there on three counts of robbing the U.S. mails, he was sentenced to life at hard labor at the West Virginia State Penitentiary in Moundsville. A model prisoner, White gained the confidence of prison officials, who lobbied politicians in both Texas and West Virginia on his behalf. Obtaining a pardon from outgoing President Rutherford B. Hayes, the 26-year-oldex-con was released on March 8, 1881.

On returning to Bastrop County, White was promptly arrested by the sheriff on the outstanding warrant for the 1875 murder of James Rowe. In short order the fugitive jumped bail, fled the county and committed another series of stagecoach robberies. That May in east-central Texas he attempted three stage holdups, failing to stop one and retrieving little of value from the other two. On June 3 he robbed a stage near Gainesville, getting little from the three passengers but $1,000 from the mailbags. Moving on to Arkansas, White on June 15 stopped both the northbound Alma-to-Fayetteville stage and its southbound sister stage, which happened on the scene. Brandishing a pistol, he bound and blindfolded the drivers and their passengers, robbing them and taking the U.S. mail.

Shifting his sights west to Colorado, White robbed the Del Norte-to-Alamosa stage near Alamosa on the night of June 28–29 in a well-planned operation. Indeed, his preparations were elaborate. Blocking the stage by placing a canvas-shrouded tree limb in the road, he stopped it at pistol point. Aboard were 13 passengers, including a woman. Using a tripod-mounted reflector lamp to blind the driver and passengers, White bound their hands and shrouded their heads with cloth hoods. True to form, he refused to rob the female passenger or a one-armed male passenger and allowed another man to keep his gold watch. Still, White pocketed at least $1,800 from the U.S. mail and passengers before riding off, leaving the driver and passengers to free themselves and make their way to Alamosa.

GET HISTORY’S GREATEST TALES—RIGHT IN YOUR INBOX

Subscribe to our HistoryNet Now! newsletter for the best of the past, delivered every Monday and Thursday.

Arrested in Pueblo on June 29, White escaped from a moving train while being transported to Denver, only to be recaptured. Convicted in Pueblo for the Alamosa robbery, he was sentenced to life at hard labor at the Wyoming Territorial Penitentiary in Laramie. After White made another unsuccessful break for freedom, authorities decided the penitentiary wasn’t secure enough to hold him and ordered his transfer to the Detroit House of Correction in Michigan. While being transported there by train, he picked the lock on his handcuffs, attacked the escorting officer and secured his revolver. This latest escape attempt also failed, however, when Mrs. Alice Smithson of Denver, described as a “plucky woman,” choked White until others managed to subdue the prisoner.

White had served less than six months in the Detroit House of Correction when the U.S. Department of Justice deemed that facility insufficient for an escape artist of his talents. When the warden of Philadelphia’s Eastern State Penitentiary refused to receive White, authorities delivered him instead to the Albany County Penitentiary in New York, amid considerable publicity.

White’s lawyers ultimately succeeded where their client had failed, effecting his release from prison in January 1887 owing to technical irregularities in his trial. Returning to Texas, White on July 28 again held up sister stagecoaches—the Austin-to-Fredericksburg and Fredericksburg-to-Austin stages—near Dripping Springs, in Hays County. Neither was carrying passengers, however, and he realized little from the U.S. mail.

On the night of September 29, at a spot outside Ballinger called Nichols’ Pasture, White robbed the San Angelo-to-Ballinger stage and, three hours later, the Ballinger-to-San Angelo stage. Following his usual modus operandi, he blindfolded the passengers, engaged in friendly banter with them and refused to rob the women aboard. Four nights later he robbed the San Angelo-to-Ballinger stage at the same location, taking the U.S. mail off the same driver, William Ellis. The very next night at the same location he robbed a buggy carrying the U.S. mail.

Later that year White, going by the alias Henry Miller, popped up in the small town of Stephensville, in Erath County, where he married Nannie C. Scott on December 7. The couple settled in Duffau, also in Erath County. Little else is known Nannie Miller or their domestic life.

The following spring White was back at his profession. On April 20, 1888, returning to Nichols’ Pasture a fourth time, he robbed two conveyances—the San Angelo-to-Ballinger stage, again driven by the now familiar William Ellis, and a two-horse hack driven by Al Jacks. He blindfolded both drivers and all 10 passengers. While waiting for the Ballinger-to-San Angelo stage, which never came, he again curried favor with the passengers, going so far as to issue a hand-scrawled certificate absolving the unarmed male passengers of any charge of cowardice and returning to each enough money for a meal.

On June 23 White held up the San Angelo-to-Ballinger stage once more, this time near Willow Water Hole Station and while traveling afoot. The driver was Jacks. White blindfolded the seven passengers, relieved them of their money, shared drinks all around from a whiskey flask one had been carrying, then rode off bareback on one of the stagecoach horses.

White returned to wife Nannie in Erath County before moving with her to Arizona Territory. Ham was far from through with stage robbery, though.

In and Out of Prison

On Nov. 23, 1888, at Oneida Station, near Casa Grande, A.T., White awaited the Florence-to-Casa Grande stage. He was masked, wielded a sawed-off shotgun and had wrapped a blanket around his hips to conceal his limp. While waiting, he detained and robbed a doctor in a buggy and stopped but did not rob a man driving a wagon. As the stage approached, the driver, spotting White and his victims, believed he was being robbed by three men and quickly stopped. White relieved him of four mailbags and a Wells Fargo express box.

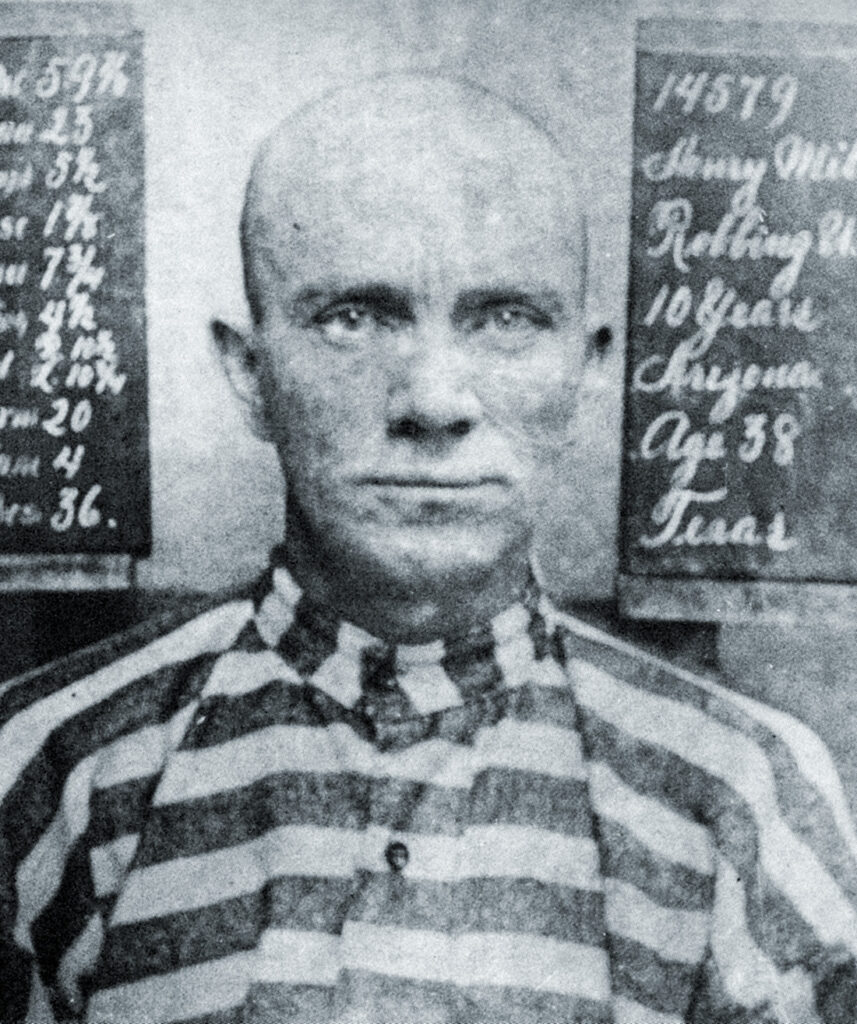

Foolishly, this time White trailed the stage into Casa Grande, where he was promptly recognized and arrested. In a plea bargain he admitted to one count of robbery of the Wells Fargo express box and was sentenced to a dozen years at the Yuma Territorial Prison.

In prison White learned to make walking canes and expanded the craft into a viable business. With his earnings he was able to both support his wife and hire a law firm to look into a pardon. On Jan. 20, 1891, acting Governor Oakes Murphy did pardon White, ostensibly owing to his restoration of the loot from his last holdup, his commendable support of his wife and his undeniable industriousness. It didn’t hurt that the prison at Yuma was overcrowded, or that White had sat trial under his alias, Henry Miller, and authorities were embarrassingly unaware their prisoner was, in fact, repeat offender Ham White.

Though his newly learned craft offered a respectable career, White couldn’t resist robbing stagecoaches. On March 7 he attempted to rob the Weaverville-to-Redding stage just outside Redding, Calif., but the preoccupied driver passed him by. White then exchanged fire with shotgun messenger Henry Ward and wounded the driver, though not seriously. On March 19 White again tried to rob the same stage. This time the driver noticed him, no messenger was riding shotgun, and Ham managed to stop the stage at the point of a revolver. Ignoring the two passengers, he demanded two express boxes and made off with an undisclosed amount of gold.

Four days later authorities arrested White in Los Angeles. Convicted that May in federal court in Florence, A.T., of the Casa Grande robbery of the U.S. mails, he was sentenced to 10 years at hard labor at California’s San Quentin State Prison. Weeks later, attempting to escape while en route to San Francisco, he got lost in the Arizona Territory desert and was turned in by local ranch hands. White finally arrived at San Quentin on June 15. Managing again through good behavior to get his sentence reduced, he was released on Dec. 26, 1897. While in prison he’d contracted tuberculosis.

By then in his 40s, ill and likely demoralized, White resorted to increasingly desperate measures to earn a living. On May 15, 1898, he tried to stop a locomotive on the San Antonio & Aransas Pass Railroad, but the train simply plowed through the obstacles he’d placed on the track. He then tried to extort money from the same railroad by anonymously threatening damages before actually setting fire to a cotton platform and a bridge. Authorities finally caught up to him on June 21 as he sought to collect $6,500 in extortion money. Convicted in Bexar County of conspiracy to destroy and injure a railroad, White was sentenced to two years in the Texas State Penitentiary at Huntsville. Transferred to a prison farm in Colorado County, he escaped on June 16, 1899. After a brief visit to brother John’s home near Bastrop, White held up travelers in Llano County. Arrested for the last time in Hays County on July 10, he was convicted of robbery in Llano County and sentenced to 15 years at Huntsville, concurrent with his unexpired term for conspiracy. Owing to White’s tuberculosis, authorities transferred him to the Wynne Farm, a Huntsville sanitarium for ailing convicts, where he died on Dec. 27, 1900.

Black Bart

Charles E. Boles (aka Charles Bolton, aka Black Bart) was born in England in 1829. His family immigrated to America the following year and took up farming in Jefferson County, N.Y. In 1849 and again in ’52 Charles tried his luck in the California goldfields, first with cousin David, then joined by brother Robert. Like most other hopefuls they failed to hit pay dirt, then David and Robert fell ill and died. Charles returned home, married and fathered four children. A dutiful Northerner, he enlisted in the Union Army at the outset of the Civil War. Boles distinguished himself in combat, participating in 17 battles and being thrice wounded. But the harrowing experience did little to temper his gold fever. In 1867 he left for the Montana Territory goldfields, abandoning his wife and kids.

By 1875 Boles was leading the life of a San Francisco gentleman, his frequent absences from town ostensibly for the purpose of overseeing his mining interests. In fact, he supported his extravagant lifestyle by robbing stagecoaches passing through his former haunts in gold country. The unsuccessful prospector had found a more creative way of mining gold and turned out to be a highly successful road agent.

Ever the gentleman, Boles was always scrupulously polite and never robbed passengers, going so far as to hand back a purse tossed from a stage by a frightened female passenger. His interest was only in the Wells Fargo express box and the U.S. mail. He would wait for a stage at a point in the road where the driver was forced to slow his team, such as an upward incline. Brandishing a shotgun, Boles would block the lead horse and so halt the vehicle. He disguised himself in a flour sack mask and long linen duster, sometimes also covering his boots with sacks or rags. He worked alone, approached stages afoot and avoided any with armed messengers aboard. Indeed, he fled at the least sign of armed resistance and later claimed his shotgun was always unloaded. Though older than most road agents—in his 40s and 50s at the time of his robberies—he was capable of hiking long distances and consistently able to evade mounted posses. Known for his whimsical temperament, he left original poems at two of his holdup sites, signing them “Black Bart, the P o 8.”

For eight years Boles proved a thorn in the side of James B. Hume, Wells Fargo’s chief detective. Black Bart’s undoing came during his foiled last holdup attempt, on Nov. 3, 1883, when the wounded, fleeing road agent inadvertently left behind a handkerchief with a laundry mark. Detective Harry Morse, an associate of Hume, managed to trace the handkerchief to a San Francisco laundry, which identified the owner as Charles Boles. Black Bart served four years and two months in San Quentin. On his release he may have engaged in three additional stagecoach robberies before seemingly vanishing from history.

Head to Head

So, how do these storied road agents compare?

The older of the pair when active, Black Bart worked alone, was well disguised, took fewer risks and stuck to a tried-and-true methodology. Steering clear of the richer pickings aboard stagecoaches guarded by shotgun messengers, he preferred to forgo risk and settle for more meager returns. Indeed, despite his heroic military record, he avoided violence and literally ran away when confronted by armed resistance. Boles was very polite and never robbed

passengers. His interest lay solely in the Wells Fargo box and the U.S. mail.

Ham White was a younger man, in his 20s and 30s during his road agent career. Like Black Bart, he worked alone and was polite and accommodating to passengers, though, unlike Boles, he did rob them. While both men sought to avoid violence, White did shoot a driver on one occasion. There were also differences in their techniques. Boles used a shotgun, or at least brandished one, while White generally used a pistol. Boles always approached stages afoot, while White often robbed them from horseback. Boles was always masked. Though White used a mask on occasion, he more often bound his victims and then put hoods or blindfolds on them.

White took more risks, such as robbing passing stagecoaches on the same line on the same day and returning to the same site for multiple robberies. He did exhibit flashes of genuine ingenuity, as the 1881 Alamosa robbery clearly demonstrates. But his record as a road agent proved far more erratic than that of Boles, and he often displayed serious lapses in judgment. In March 1877, for example, he visited family in Bastrop County, risking arrest for murder. That same month he called attention to himself in a spending spree that got him arrested by Texas Rangers in Luling. Most egregious, after the 1888 Casa Grande robbery he showed up at the destination of the robbed stagecoach, practically asking to be recognized and caught.

White employed his considerable creative talents to escape custody—legally and illegally—on several occasions. Black Bart, on the other hand, fully cooperated with authorities when arrested.

When evaluating the “performance” of a road agent, three criteria present themselves: The number of stagecoaches waylaid, the aggregate value of loot stolen and the cumulative time spent in prison.

Black Bart wins the first category, having committed some 30 stage robberies to White’s two dozen.

It is difficult if not impossible to assess the value of the respective loot each road agent stole, as newspaper reports varied or were inaccurate. Complicating matters, the U.S. Post Office usually didn’t report the value of stolen mail, and companies like Wells Fargo had a vested interest in underreporting losses, as robberies were bad for business. That said, Black Bart lived the life of a San Francisco gentleman on his ill-gotten gains, while Ham White enjoyed no such luxury.

It is when considering the time each spent in prison the comparison proves especially stark. Boles spent just over four years behind bars, while White’s time in custody adds up to nearly 21 years. Even if we omit White’s incarcerations for crimes other than stage robbery, we still arrive at a stiff 18-plus years.

Taken as a whole, then, it appears Black Bart merits his title as the premier lone stagecoach robber of the American West.

For further reading on this topic author Daniel R. Seligman recommends Knight of the Road: The Life of Highwayman Ham White, by Mark Dugan; Black Bart: The True Story of the West’s Most Famous Stagecoach Robber, by William Collins and Bruce Levene; and Gentleman Bandit: The True Story of Black Bart, the Old West’s Most Infamous Stagecoach Robber, by John Boessenecker.