Austria was the first country to fall to Nazi Germany, but it functioned less like an occupied nation and more like a loyal vassal state. When the German Army crossed the border into Austria in the early hours of March 12, 1938, its progress turned into a victory parade. Austrians filled the streets of their towns and threw their arms up in salute. Some even handed flowers to the passing soldiers or tossed swastika confetti. A British tourist wrote in her journal that the chants of “Sieg Heil” and “One people—one empire—one Leader” were “so repeated that it sounded like a giant pulse beating in your ear.” At Linz, not far from Adolf Hitler’s hometown of Braunau am Inn, “even the trees and streetlamps were full of screaming, shouting people,” one resident remembered.

In CBS Radio’s inaugural “World News Roundup” broadcast on March 13, Edward R. Murrow reported from Vienna. “They lift the right arm a little higher here than in Berlin and the ‘Heil Hitler’ is said a little bit louder,” he noted. With a language and culture shared with Germany, Austrians became fully amalgamated within the Third Reich; in fact, Austrians were the only non-Germans who could become officers in the German armed forces, the Wehrmacht.

Because of the high degree of support for Germany, the fragile pockets of Austrian resistance against the Nazis during the war had to operate differently from those in occupied countries like France or Norway, which had well-armed and wide-ranging networks. Austria’s resistance was not only smaller and more precarious than that of other countries, but it also originated from a more motley collection of motivations. Resistors included politically organized Communists, devout Catholics, apolitical pacifists, and Austrian Legitimists who sought to restore the monarchy under Otto von Habsburg, a prominent voice of Nazi resistance and heir apparent of the Habsburg family dynasty.

As time went on, though, several of these disparate groups began to coalesce around two men. The first, Franz Josef Messner, was the successful general director and chairman of Semperit, a major tire manufacturer. The second was a young and outgoing Catholic chaplain named Heinrich Maier, who served as a priest in an upscale Vienna suburb and had leftist leanings that originated from his humble childhood. The two formed a group whose appellations were as varied as its members. At times it was referred to as O5, Arcel, CASSIA, or eventually the Maier-Messner Group. Despite all odds and with no background in espionage, the Maier-Messner Group began to accumulate information it could use against the Nazis and remained operating until nearly the end of the war.

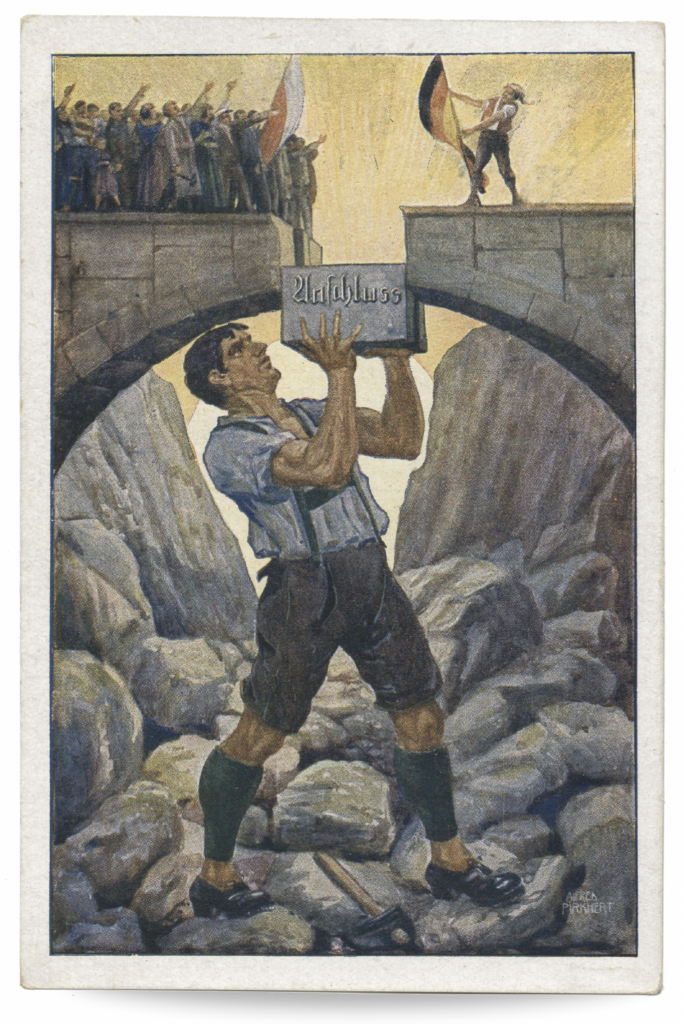

The collapse of the 600-year-old Habsburg Empire and the end of World War I in 1918 led to runaway inflation, instability, and unemployment in Austria and created a political vacuum. Unification with Germany appealed to many struggling Austrian citizens during the worldwide Depression of the 1930s because it promised economic stability and an echo of the time when the Habsburg Empire sprawled across the continent. Hitler promised to spread in Austria what he called the “flourishing new life of Germany.”

“Austria’s own legacy of German Nationalism was hugely important for the Nazis,” explains Dr. Meyer Weinshel of the Center for Austrian Studies at the University of Minnesota, “and it meant that resistance to the Nazi regime was pretty muted.” The majority of Austrians supported the new regime, at least passively. “Aryan Austrians served in every level of Nazi bureaucracy,” Weinshel points out, with 1.2 million Austrians serving in the Wehrmacht (out of a total wartime population of 6.5 million). Austria provided nearly half of the Schutzstaffel (SS) and staff who served at concentration camps. Before entering the country later in the war, American spies were warned, “You can expect ninety percent of [western Austrians] to be pro-Nazi.”

The annexation of Austria with Nazi Germany became known as the Anschluss, which literally translates as “connection.” It was not a conquest by Germany—it was a seamless reunion. The nationwide support of the Third Reich within Austria made it extremely difficult for resistors to establish and expand cells and avoid betrayal by coworkers, friends, and even family members who were more than willing to inform on anyone less than devoted to the new regime. An Austrian resident turned refugee recalled, “People looked on the Anschluss, first and foremost, as an opportunity to get involved in the witch hunt.”

Yet even while celebratory chants still rang through the streets of Vienna, an unlikely resistance cell was already forming, spearheaded by two contrasting personalities. The silver-haired businessman Franz Josef Messner, born in 1896, was worldly and confident where Heinrich Maier, more than 11 years younger, was modest and friendly, but the two had bonded two years before, in 1936, over their concerns about the future of Austria and wider Europe. They became even more worried following the disturbing events of the Anschluss. A later report claimed that “Maier found in Dr. Messner a comrade. He shared with Messner all of his political endeavours and asked Messner, because of his many business trips abroad, to acquire information.” Messner’s connections included officials from Semperit in Austria, Hungary, and Turkey who had exclusive industrial and economic knowledge about Germany.

Because of its circumscribed and perilous position, the Maier-Messner Group initially focused on nonconfrontational measures, such as collecting intelligence, engaging in anti-Nazi propaganda work (leaflets described Hitler as the “greatest curse-laden criminal of all time”), and helping to excuse conscientious objectors from frontline service. The group had early stumbles but quickly learned and recalibrated.

By the end of 1940, less than two years after the Anschluss, the Gestapo had infiltrated and destroyed most Communist, Legitimist, and Catholic resistance cells while building a powerful and expansive informer network. However, the Maier-Messner Group—small, nimble, and with a mélange of motivations—not only persisted but expanded, eventually totaling about 20 members, despite operating in one of the most hostile environments for any wartime spies.

Maier did have allies within the church. Conservative Catholics had long been suspicious of a too-close connection to Germany and its Protestant majority, and the Nazi regime didn’t trust the power of the church in an Austria that was 90 percent Catholic. Hitler once wrote, “Every national idea was sabotaged by Austria throughout history; and indeed, all this sabotage was the chief activity of the Habsburgs and the Catholic Church.” Post-Anschluss, the government began to reduce the power of the church by allowing divorcées to remarry, closing parochial schools, and confiscating church-owned lands. After a sermon in which he called Jesus Christ “the one Führer,” the Archbishop of Vienna had his residence stormed by furious Nazi devotees, who destroyed furniture and set his papers on fire. With memories of past clerical overreach still fresh, many Austrians welcomed the limits on church power.

This was the climate within which the liberal and intellectual Maier operated. Since 1935 the energetic priest had served as the curate of the redbrick Gersthof Parish Church in Vienna’s 18th district. The church’s soaring bell tower was visible from Messner’s landscaped villa a few blocks away. According to Christopher Turner in The CASSIA Spy Ring in World War II Austria, Messner had the business connections, but Maier was “equally as—if not more—important than Messner, for his unwavering morality and beliefs had defined the group’s common purpose and had demanded loyalty among its sundry members.” He had built up a broad social network across all rungs of the ladder of Viennese society and his Neo-Gothic church likely served as a meeting spot where conspirators could pass unobserved, or at least unremarked upon.

Maier also had connections to a small but strategically useful arm of resistance within the Austrian military through a longtime friendship with the family of Heinrich Stümpfl, a general staff officer whose traditional military beliefs conflicted with Nazi ideology. Maier confessed his resistance activities to Stümpfl, who then helped to pass on intelligence about the Wehrmacht’s numbers and positions in Austria. Germany had set up much of its military infrastructure in Austria, since it was out of range of Allied bombers in the early part of the war.

The members of the Maier-Messner Group bided their time and conserved their limited resources, both material and personnel, as they painstakingly built a trove of information. In the summer of 1942, Maier composed a memo on behalf of the group for the British and Soviet foreign ministers, delivered in Switzerland through a Catholic theologian, Maier’s only contact on neutral soil. The man delivered the message, but it was ignored by both countries. For its part, the British foreign intelligence agency MI6 believed the group was too good to be true and feared that the overtures were part of a German disinformation campaign. But Maier and Messner remained undaunted.

Maier had befriended and then recruited Barbara Issakides, a classical pianist who wasn’t especially political but was disgusted enough with Hitler to take on the risks of resistance. While in Switzerland for a concert at the end of 1942, she established contact with Allen Dulles, the director of the Swiss branch of the Office of Strategic Services (OSS), the U.S. intelligence agency. Dulles, who would go on to head the Central Intelligence Agency after the war, had heard rumors of the group but wondered if it even existed. After Issakides made contact, Messner signed a contract with the OSS. His resistance cell would soon become the most effective spy ring the Allies had within Austria.

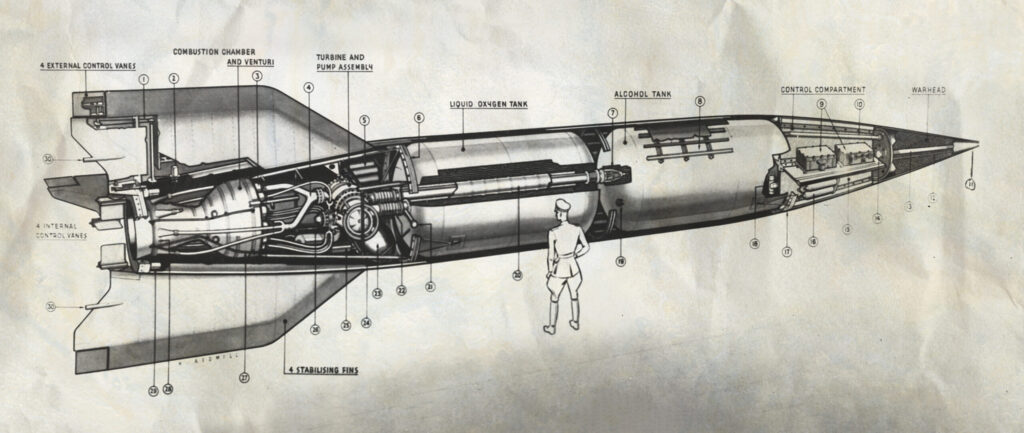

Among the most important pieces of intelligence the Maier-Messner Group provided the Allies was the design of the V-2 rocket, the first long-range ballistic missile, in late June 1943. Dulles cited a report in which he credited an “Austrian source” with providing “much of the technical information on the rockets.” Messner may have received his information from his Semperit contacts. After he pinpointed the locations where V-2 rockets were assembled and tested in Germany, American and British bombers carried out precision air strikes.

The Maier-Messner Group also shared with the OSS the first intelligence on Germany’s formulation of synthetic rubber, a vital substance for the Third Reich since it had no sources for natural rubber. The intelligence included the coordinates and production estimates for three rubber factories. Messner’s role in the tire industry also allowed him to uncover plans to enhance German U-boats with sonar-resistant rubber panels. In addition, the group provided accurate drawings of the Tiger I, a heavy tank Germany used in the Soviet Union and North Africa. In some cases, Maier learned of developments from parishioners on leave from the front.

The group’s most shocking revelation was the existence of concentration camps and Germany’s mass extermination of Jews, intelligence that at first seemed absurd to the Americans. Messner gained the first evidence of this from his sources within a Semperit plant 200 miles north of the concentration camp at Auschwitz.

In the meantime, the Austrian government was cracking down on the Catholic resistance. The Nazis executed Sister Maria Restituta Kafka in 1943 as “effective intimidation” so others wouldn’t be emboldened by her vocal disagreement with Hitler or her refusal to remove crucifixes from the hospital where she worked. Catholic conscientious objector Franz Jägerstätter was also executed that same year. A police informer exposed the Austrian Liberation Movement—about one hundred Catholic Legitimists organized by another priest—and its collaborators were sentenced to death.

Violence was of course not limited to Catholics. Among the common chants heard on the streets was “Jew—perish.” Austrian radio announcers provided a gleeful play-by-play of the burning of the largest synagogue in Vienna during Kristallnacht, and resident Sigmund Freud fled his longtime practice for sanctuary in England shortly after the Anschluss. Before the war, Vienna had been home to a thriving Jewish community of nearly 200,000. More than 65,000 of them were murdered in the Holocaust.

The Maier-Messner Group continued with their work despite the growing danger. In the late summer of 1943, Issakides traveled with Messner to Switzerland under the pretext of a business trip so they could deliver high-level intelligence that would help Allied bombing missions target war-related factories and other military targets, thereby also sparing civilians.

Sometime in the winter of 1942-1943, Maier met a student at the University of Agriculture, a school only 15 minutes from his church. The young man, Walter Caldonazzi, was a devout Catholic and a fellow member of Maier’s old student fraternity of Legitimists. Despite physical limitations from a childhood injury that left him with a limp and using a cane, Caldonazzi collected intelligence on some of Germany’s crucial armament factories, particularly those that produced the brass used by the Nazi war machine for shell casings, gear wheels, and ball bearings. The Maier-Messner Group’s couriers transmitted these materials to the OSS, which in turn passed this on to Allied bombing commands.

Dulles trusted the intelligence he received from what he referred to as his “well placed but non-technical source.” As the Allies began coordinating military operations within Austria, the Maier-Messner Group pledged its on-the-ground support. In March 1944, the OSS began devising an operation to infiltrate Austria via parachutists, who would then be received by members of the spy network once they landed.

However, the group’s luck was about to run out. The head of the Semperit plant in Istanbul, a member of the Maier-Messner Group, was looking for an Allied agent in neutral Turkey to pass along his cache of information. The agent he found was operating a ponderous and unchecked espionage network that had been infiltrated by German double agents. They were able to trace the source of the intelligence provided by the Maier-Messner member to uncover the identities of the group’s collaborators.

On January 15, 1944, the Gestapo arrested Walter Caldonazzi for interrogation at the secret police’s Vienna headquarters in the once stylish Hotel Metropole, now the largest Gestapo office outside of Berlin. The formerly luxurious hotel rooms had been reconfigured into dark, soundproof cells where approximately 50,000 prisoners were interrogated and tortured; several died there, either from injuries or suicide. Future Chancellor of Austria Bruno Kreisky recalled his experience at the Hotel Metropole after an arrest for socialist political activity: “I underwent a very unpleasant and harsh interrogation,” he said. “Half unconscious and covered in blood, I came back into the cell. With an Überschwung—that’s how the wide military belt was called—they knocked out two of my teeth.” In a jailhouse letter, Caldonazzi stated, “I was threatened during my second twelve-hour interrogation that, if I continued my denials, [the Gestapo] would arrest my bride, parents, and others.”

The OSS lost all contact with the resistance group. Within six months, the Gestapo had completely dismantled the network and arrested nearly all the leading members. Messner and Maier were both arrested at the end of March 1944— two Gestapo agents seized the priest at his church immediately after he had conducted mass and they took him to the Hotel Metropole.

It is likely that the Gestapo tortured all the members of the Maier-Messner Group they arrested. Over the next month, the prisoners began to divulge some of the group’s activities and the names of co-conspirators. Maier had the most comprehensive understanding of the group’s membership and activities, and the most incriminating testimony surfaced when the priest confessed that Messner had established contact with the Allies and accepted money from them to fund the group’s activities.

Maier spent the rest of his time in prison learning languages, praying, and writing to friends and family. In one of his last letters, Maier wrote, “I die happy. I am now well prepared for death. What I did, I cannot regret. I did it for Austria.”

On October 27, 1944, the Gestapo presented its evidence in a trial against 10 of the group’s conspirators, including Maier, Messner, and Caldonazzi. Issakides may have attended as a witness. (Maier had denied any knowledge of her complicity, thereby saving her from being charged.) All three men were found guilty of “preparation for treason” and “participating in a separatist union” and sentenced to death. The Nazis dispatched them to Mauthausen, the only Austrian concentration camp, where slave laborers quarried granite and performed munitions work.

Caldonazzi was beheaded at the Vienna Regional Court in January 1945. After his conviction, Maier spent months at Mauthausen, where he was tortured and humiliated. He was brought back to the Vienna Regional Court and beheaded on the evening of March 22. His last words were “Long live Christ, the king! Long live Austria!”

Messner was executed at Mauthausen a month later. “On 23 April 1945 at 1500 hours, Commander SS-Standartenführer Franz Ziereis personally came to the bunker and ordered me to take forty prisoners, among them Dr. Franz Messner, to the gas chamber,” a senior squad leader reported. “While leaving his cell, Messner wanted to tell me something, but the commander’s presence prevented that…. The commander himself initiated the flow of poison gas.”

Messner died only days from rescue. Twelve days after his death, the U.S. 11th Armored Division liberated Mauthausen. By then the Soviets had captured Vienna and the Hotel Metropole had been reduced to bombed-out ruins.

In the Moscow Declarations issued in October 1943, U.S. and Soviet foreign ministers agreed that Austria was “the first free country to fall victim to Hitlerite aggression.” However, they also noted that the country “has a responsibility which she cannot evade, for participation in the war at the side of Hitlerite Germany.” For decades afterward, the Austrian government emphasized its victimhood, rather than its responsibility. Many Austrians continued to view resistance fighters as draft dodgers, if not traitors. By the 1990s, the Austrian government finally admitted that the country bore “co-responsibility” for Nazi atrocities. Yet, while the total number of murdered Austrian resistance fighters lies between four to five thousand, there is little tangible trace of their memory today, even for those from the country’s most successful intelligence-gathering operation.

One of the few memorials to those who took on the fight against the Third Reich in what was the mouth of the beast is near a busy U-Bahn station in Vienna, across from what was once the site of the foreboding Hotel Metropole. Today all that remains is a green square with a scattering of trees. In one corner of the square stands a small and easily overlooked monument. Made from blocks of Mauthausen granite, the memorial’s weather-streaked walls shelter the sculpture of a defiant prisoner. Inscribed in one stone is a dedication in German:

Here stood the House of the Gestapo.

To those who believed in Austria it was hell.

To many it was the gates to death.

It sank into ruins just like the Thousand Year Reich.

But Austria was resurrected and with

her our dead, the immortal victims.