Easter came early in 1972 and the North Vietnamese Army (NVA) came with it. On March 30, “Holy Thursday,” three NVA divisions stormed out of Laos and across the DMZ. It was the first of multiple assaults that struck not only the northern provinces of South Vietnam but also Kontum in the Central Highlands and An Loc, only 60 miles north of Saigon.

North Vietnam was “going for broke,” committing its entire combat capability—14 divisions and 26 separate regiments, all with attached armor and heavy artillery units. Enemy forces numbered 130,000 troops and 1,200 tracked vehicles, primarily tanks. Aging Communist revolutionaries controlling Hanoi’s Politburo believed the time was right to achieve a decisive military victory, topple South Vietnam’s government, and embarrass the United States.

As U.S. military personnel continued to withdraw, American troop strength was brought down to 69,000. Only two U.S. combat brigades remained—their missions were restricted to guarding airbases and patrolling the surrounding areas. Although the Military Assistance Command, Vietnam (MACV) listed 5,300 men as “advisers,” the only Americans fighting on the ground were a handful of men serving with provincial advisory teams and Army of the Republic of Vietnam (ARVN) divisions and regiments.

As a result of Vietnamization, battalion advisers were only authorized in the Airborne Division, Marine Division, and selected Ranger units. There were also battalion advisers, mainly NCOs, with the ARVN field artillery battalions.

Americans On The Front Lines

The term “adviser” was a misnomer. By 1972, advice was rarely solicited and when offered, rarely heeded. However, U.S. advisers often cajoled and encouraged their counterparts, particularly in dire situations when spirits were flagging. The presence of even a lone American adviser was a morale booster, as every ARVN soldier knew they would not be abandoned as long as one American was with them.

The advisers’ primary role was employing the massive air assets President Richard M. Nixon had sent to South Vietnam. U.S. air power proved decisive in blunting the 1972 enemy offensive. Advisers routinely exposed themselves to NVA fire while working with USAF forward air controllers, identifying lucrative targets and adjusting air strikes to ensure bombs were “on target.”

Americans who remained on the front lines, especially advisers with airborne and Marine battalions, suffered significant casualties. Adm. Chester Nimitz’s famous quote after World War II’s Battle of Iwo Jima in 1945 was equally applicable to the advisers who helped turn back the NVA offensive 27 years later: “Uncommon valor was a common virtue.”

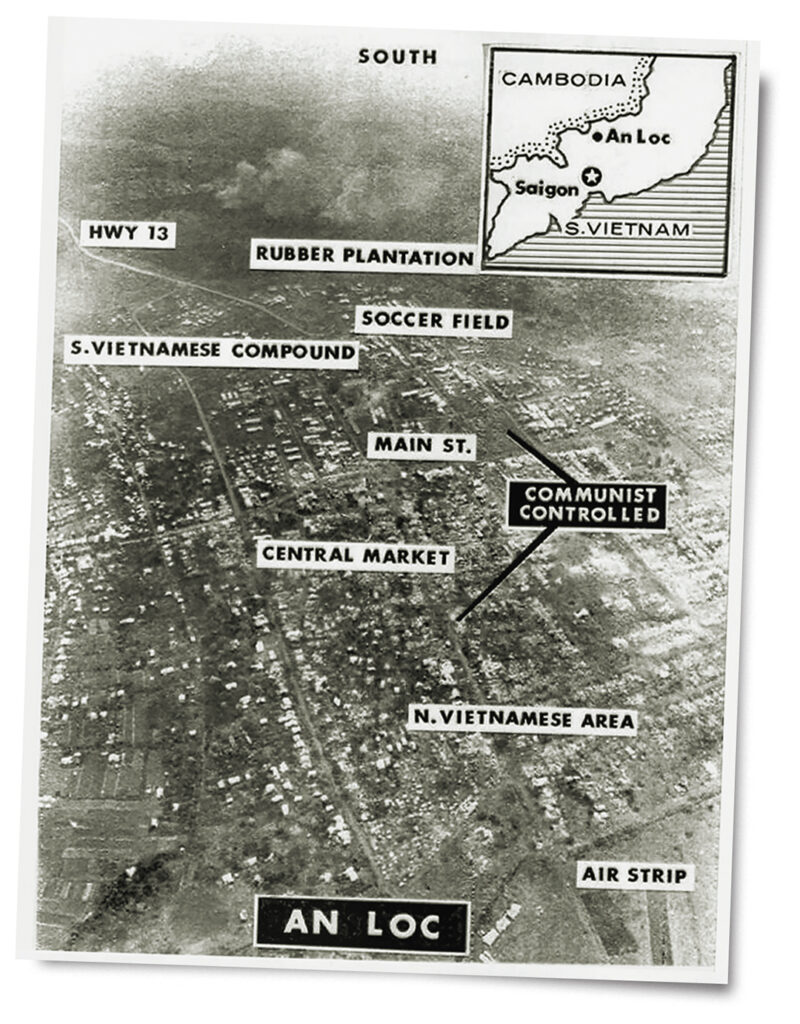

Early in 1972, allied intelligence personnel were watching NVA build-ups in Laos and Cambodia but had no idea of the timing of a possible offensive. When it occurred, the ARVN Joint General Staff (JGS) and MACV were surprised by its scale and ferocity. With fighting raging in three areas, military officials were unable to determine the communist main attack. The focus of III Corps, the ARVN headquarters responsible for provinces surrounding Saigon, was on enemy attacks in Tay Ninh. These were diversionary operations, masking the movement of three NVA units: 5th VC Division, 9th VC Division, and 7th NVA Division. The 5th and 9th were VC in name only; they were manned and equipped by the North Vietnamese Army.

The situation grew more tenuous on April 5, 1972, when those divisions—36,000 troops organized into combined arms teams of infantry, armor, heavy artillery, and engineers—poured across the Cambodian border into Binh Long Province. The immediate threat to the government in Saigon was clear.

Maj. Gen. James F. Hollingsworth, commander of the Third Regional Assistance Command (TRAC), urged Gen. Nguyen Van Minh, III Corps commander, to reinforce An Loc, the provincial capital. Hollingsworth, a 1940 graduate of Texas A&M University, was one of Gen. George S. Patton’s outstanding tank commanders during World War II. He led from the front and during his service in three wars he was awarded three Distinguished Service Crosses (DSC), the nation’s second highest award for valor, four Silver Stars and six Purple Hearts, plus four Distinguished Service Medals and 38 Air Medals.

Known as “Holly,” he was also a Korean War veteran and had served a previous Vietnam tour as assistant division commander of the famed 1st Infantry Division. Advisers revered him and were grateful for the air support he was able to muster.

A City Under Siege

The district town of Loc Ninh, a few miles from the Cambodian border, fell on April 7 when the NVA overran it, killing or capturing nearly 1,000 soldiers. Two U.S. advisers were killed and seven were listed as missing in action. Only 100 ARVN defenders and one American, Maj. Tom Davidson, managed to escape the battle and make their way to An Loc, which was 15 miles south and obviously the enemy’s next target. The 5th ARVN Division defended An Loc with three infantry regiments, two ranger battalions, and provincial forces.

If An Loc was lost, there were no ARVN troops to stop an enemy move on Saigon. President Nguyen Van Thieu issued a directive that An Loc must be held at all costs. The well-publicized order caught the attention of the communists, challenging them to quickly capture it. The pivotal battle for An Loc and the heroism of U.S. advisers there was a microcosm of the fighting throughout South Vietnam in what the U.S. press now called the Easter Offensive.

On April 7, 1972, President Thieu convened a meeting of his key advisers and corps commanders to assess the military situation; it was a grim session. General Minh outlined his circumstances and requested more troops to reinforce An Loc, surrounded by the 5th and 9th VC Divisions. He also pointed out the 7th NVA Division had cut the main supply route, QL (National Route) 13, into the provincial capital, isolating the defenders.

Because of the enemy’s proximity to Saigon, the president made the unprecedented decision to commit the country’s last reserve, the 1st Airborne Brigade, to III Corps. He also directed the 21st ARVN Division move from the relatively quiet Mekong Delta region and join the battle in Binh Long Province.

By the afternoon of April 8, the 1st Airborne Brigade, augmented by the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion, was assembled south of An Loc, ready to fight. The 81st was originally activated as a reaction force during the days of cross-border operations into Cambodia, Laos, and North Vietnam. Now, it was employed as an elite infantry battalion. It was teamed with the Airborne Division because its advisers were part of the Airborne Division Assistance Team, also designated MACV Team 162. The brigade’s 2,000-plus paratroopers were tasked to open QL 13 into An Loc. Soldiers of the 7th NVA Division, 8,600 strong, had prepared extensive defensive fortifications along the vital supply route. The NVA easily stopped the 1st Brigade.

A One-Man Operation

With a stalemate occurring, Hollingsworth recommended a mission change: reinforce An Loc with the 1st Airborne Brigade and have the 21st ARVN Division clear QL 13. The paratroopers were needed because on April 13 the NVA kicked off an armor and infantry attack that threatened the town.

Late in the afternoon of April 14, the 6th Airborne Battalion, about 400 paratroopers, conducted a helicopter assault into an LZ near key terrain just south of An Loc. Two American advisers, Maj. Richard J. Morgan and 1st Lt. Ross S. Kelly, accompanied the battalion commander, Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Dinh, in the first lift. The high ground, Hill 169 and an adjacent feature called Windy Hill, was needed for an artillery firebase. It would provide support for the 5th ARVN Division because all its guns had been destroyed by incoming fire.

Initially, the landing was unopposed. Yet the NVA reacted quickly and stopped the paratroopers from gaining the summits of the two hills. The advisers called in air strikes. Kelly, accompanying attacking troops, directed U.S. Army AH-1G Cobra rocket and machine gun fire to within 25 meters of his position, forcing the enemy to withdraw. It was a “danger close” call, but a necessary one.

As the high ground was taken, Morgan, the senior adviser with the battalion commander, suffered a severe leg wound. He needed immediate evacuation or would bleed to death. Fortunately, a U.S. Army Huey helicopter responded to Kelly’s request for a medevac. The pilots braved enemy mortar and artillery fire to rescue Morgan and five ARVN paratroopers who were also seriously wounded.

Kelly, a 1970 graduate of West Point with less than two years in the Army, was now the lone American responsible for the battalion’s desperately needed air support. The old Army expression “operating way above his pay grade” described Kelly’s circumstances.

The remaining battalions, the 5th, 8th, and 81st, plus the brigade headquarters, arrived on April 15-16. CH-47 Chinook helicopters brought in six 105mm howitzers and emplaced them on the high ground, secured by two rifle companies of the 6th Airborne Battalion. Maj. John Peyton, Morgan’s replacement, was in the airlift and joined Kelly on the afternoon of April 16. Peyton was only on the ground two days before he too was badly wounded and evacuated. Again, Kelly was a one-man operation.

The North Vietnamese commander was not about to allow an ARVN firebase to operate in his area of responsibility. Within 24 hours, NVA artillery fire destroyed all six howitzers and its stockpile of ammunition. The battalions airlifted in on the 15th and 16th were ordered to move into the town and join the 5th ARVN Division defenders who were fending off major NVA attacks. The 6th Airborne Battalion was left on its own. Two NVA regiments with eight tanks began to systematically isolate and destroy the 6th.

Kelly used every air sortie at his disposal to keep the numerically superior foe at bay. The communist commander was determined to annihilate them, regardless of the cost. By April 20, the 6th Battalion had fewer than 150 effective fighters. Seriously injured soldiers died for the lack of medical treatment. U.S. helicopters only flew medevac missions for wounded U.S. advisers—so the evacuation burden fell on the Vietnamese Air Force (VNAF) helicopter pilots, most of whom were sadly lacking fortitude.

Waiting For the NVA

Supply shortages and the VNAF’s reluctance to fly caused morale to plummet. Having grown used to the robust support from the U.S. Army, the failure of the ARVN and VNAF to perform critically needed tasks was a shock to the paratroopers, including the battalion commander. Lt. Col. Dinh was psychologically overwhelmed and stayed in his foxhole, almost in a trance. Remnants of two rifle companies on the hills, less than 50 men, were forced off and escaped to An Loc. Eighty other paratroopers, who were not on the high ground, formed a tight perimeter and waited for the NVA.

Kelly began to work what little magic he had left. He coordinated with the brigade senior adviser, Lt. Col. Art Taylor, and his deputy, Maj. Jack Todd, for assistance to allow them to break out to the south, away from An Loc. Todd called Kelly at 7:30 p.m. and said three B-52 strikes were scheduled just after dark to hit the concentrations of North Vietnamese threatening the 6th Battalion. U.S. intelligence had a good “fix” on enemy locations. The bombers would drop “danger close,” meaning less than 1,000 meters from the friendlies, the minimum safe distance from B-52 bombs.

Kelly’s cajoling and the news of the upcoming bombing strikes snapped Dinh out of his depressed state. He made the difficult decision to leave the seriously wounded soldiers behind and prepared the men to move. When the first 500-pound bombs began to fall, 80 exhausted men headed to the southeast, away from the enemy. Kelly led while Dinh, farther back in the column, kept the troops moving. The shock of three successive B-52 strikes and rapidity of movement gave the bedraggled force some breathing space.

Throughout the night and into the next day, Kelly continued to serve as “point man” for the small group. On more than one occasion, he called in air strikes on pursuing enemy troops. When Kelly found a suitable pickup zone, the adviser used U.S. air strikes to seal off the area and protect the incoming helicopters.

Finally, VNAF helicopters arrived but they only touched down briefly and several hovered a few feet off the ground, making it impossible for the walking wounded to get aboard. They were not taking any enemy fire. Without warning, they “pulled pitch”—taking off with Kelly hanging on to one UH-1’s struts and leaving 40 soldiers on the ground.

Threats from the battalion commander failed to intimidate the pilots, who refused to land again. Fortunately, the corps commander and Hollingsworth forced the VNAF to return the next day, but they only retrieved half of the 40 men left behind. Those 60 rescued paratroopers became the 6th Airborne Battalion’s nucleus as reconstitution began immediately.

On Oct. 17, 1972, Kelly was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his bravery. Without his personal example, forceful urgings, and timely orchestration of airstrikes, no one would have survived. His actions belied his rank and experience and his professionalism saved the day.

Trial By Fire

During the 6th Battalion’s ordeal, the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion was undergoing its trial by fire. It was lifted in on April 16, arriving with 450 soldiers and three U.S. advisers: Capt. Charles Huggins, senior adviser; Capt. Albert Brownfield, Huggins’ deputy; and Sgt. First Class Jesse Yearta, light weapons adviser. The unit was detached from the airborne brigade and directed to fight its way into An Loc and occupy positions in the northeastern sector of the town’s perimeter. The NVA had attacked several days earlier and gained a significant lodgment, almost to the center of the town. The communists had nearly reached the east-west thoroughfare that bisected An Loc, leading one American defender to report: “The bastards are almost to Sunset Boulevard.”

As the 81st moved off the LZ, Yearta was hit by artillery shrapnel but refused evacuation. An ARVN medic patched him up. Yearta, a hardcore soldier, continued the mission. At 36, he had come of age in the Cold War army and spent most of his career in airborne units. He was known as a “hard ass,” but the troops held him in high esteem because he was a fighter and genuinely concerned for their welfare. The Airborne Rangers of the 81st had an unbounded affection for Yearta.

On the night of April 22, the battalion was directed to launch a counterattack to eliminate enemy positions. Huggins was provided a Spectre gunship, a USAF AC-130 aircraft equipped with a 105mm cannon and twin 40mm Bofors guns, to assist the attackers. The Spectre had cutting edge technology sensors that allowed it to fire very near friendly forces, almost within the 50- meter bursting radius of the 105mm shells. A rolling barrage was planned with the troops following closely behind it.

Yearta volunteered to accompany the lead company so he could direct the Spectre’s fire. Not taking a chance that he might become separated from his radio operator, he carried his own AN-PRC 77 radio so he could maintain constant contact with the airplane. To ensure the Spectre gun crew could track the leading friendlies amid battlefield obscuration, Yearta continually fired small pen flares that the aircraft’s sensors easily identified. He adjusted both the 105mm cannon and the Bofor guns by constantly sending corrections, positioning himself almost within the blast area. The fire was so devastating the NVA was pushed back and original defensive positions were restored.

Later, Yearta was asked about the Spectre’s support that night. He replied in typical fashion, “Damn! They are good ol’ boys.” Yearta became a legend among the advisers for the pen flare episode and was later awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for his valor.

The siege of An Loc lasted 66 days and resulted in the destruction of three NVA divisions. It was ironic that the reconstituted 6th Airborne Battalion, still commanded by Lt. Col. Nguyen Van Dinh, broke the enemy’s grip on the town. On June 8, 1972, the 6th Airborne linked with the town’s defenders after fighting its way from the south. In mid-June, President Thieu declared the siege lifted and the 1st Airborne Brigade was sent to the northernmost province of Quang Tri to participate in a counteroffensive.

“The Battle That Saved Saigon”

The 1st Airborne Brigade and the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion paid a heavy price for their part in what some journalists called the “battle that saved Saigon.” From April 7 thru June 21, the 1st Airborne suffered 346 killed in action (KIA), 1,093 wounded, and 66 missing; the 81st lost 61 KIA and 299 wounded.

The An Loc campaign took its toll on MACV Team 162. Nineteen airborne advisers began the operation in April 1972. Of that number, 10 were wounded and one, Sgt. First Class Alberto Ortiz Jr., died from his wounds. He was the first of five airborne advisers killed during the Easter Offensive. One officer, Capt. Ed Donaldson, was wounded on April 7, evacuated, returned to duty in An Loc, and was wounded again, for which he required extended hospitalization.

Five battalion advisers with the 1st Airborne Brigade and the 81st Airborne Ranger Battalion were awarded the Distinguished Service Cross for their actions in An Loc. In addition to Kelly and Yearta, DSCs were awarded to: Capt. Michael E. McDermott, 5th Airborne Battalion; Capt. Charles R. Huggins, 81st Airborne Rangers; and 1st Lt. Winston A.L. Cover, 8th Airborne Battalion. For McDermott, it was his second DSC, the first being presented in 1967 when he was a lieutenant in the 101st Airborne Division. With two DSCs, a Silver Star, and a Purple Heart, McDermott became one of the most decorated soldiers of the Vietnam conflict.

An Loc was destroyed in the Easter Offensive. Only rubble and burned-out communist tanks remained. The town was rebuilt and today commerce flourishes. One would not know that a climactic struggle occurred there five decades ago; there is no evidence of the battle. Several cemeteries are located just south of An Loc where the remains of NVA soldiers are interred. At each cemetery, there is a large statue and plaque dedicated to the heroism and sacrifice of the communist “freedom fighters.”

After South Vietnam surrendered in April 1975, NVA soldiers desecrated the 81st Airborne Ranger cemetery in An Loc that the town’s citizens had meticulously tended to when the 1972 battle ended. Like other ARVN cemeteries, there is no trace of it today.

During the 1972 Easter Offensive, John Howard served as senior adviser with the reconstituted 6th Airborne Battalion and 11th Airborne Battalion. On a 2011 trip to Vietnam, he returned to Tan Khai and An Loc. For further reading he recommends James H. Willbanks’ book, The Battle of An Loc and Dale Andradé’s book America’s Last Vietnam Battle.

This story appeared in the 2023 Autumn issue of Vietnam magazine.

historynet magazines

Our 9 best-selling history titles feature in-depth storytelling and iconic imagery to engage and inform on the people, the wars, and the events that shaped America and the world.